On October 4, 2012 the Swann Auction Galleries offered a photograph by Robert Frank which was titled “‘For Dave Heath’ (Self-Portrait One)” for sale. [Sale 2288 Lot 193.] An interested individual contacted me and inquired about my knowledge of the photograph. This narrative has been written to explain the context of the creation of this photograph, which otherwise must seem to be a rather puzzling image. As the provenance of the picture is from the now defunct Polaroid Collection, I assume that it was given to or purchased by the Collection as part of the normal procedure of the Polaroid 20” x 24” Studio program then in place. It was then the practice that for free access to the camera and studio the artist would donate a print from their session to the Polaroid Collection. In March 1985 Robert Frank made two multi-print suites of prints at the Polaroid studio. The photograph titled “‘For Dave Heath’ (Self Portrait One)” is probably an alternative print from that session or a copy, made with the artist’s permission, of one portrait in a larger suite of six prints made by him which is titled “Boston, March 20th, 1985.”(1) While the Frank photograph was not made directly under that program, it is possible that the artist followed a similar practice and either donated or sold the print to the Polaroid Collection.

William Johnson

October 2012

“THE ‘POLAROID PROJECT’”

On March 19, 1985 Robert Frank flew into Boston from New York City, bringing with him a small bag with a change of clothing and a paper grocery sack filled with stuff that looked like litter picked up off the streets: old newspapers or scraps of paper, tubes of black or red paint, bits of charcoal, fragments of old photographs, contact prints, and a number of very battered-looking, pin-holed, plywood-backed, cork boards; which were from an old movie theater. His purpose in coming to Boston was to spend several days making some work using one of the two Polaroid 20” x 24” cameras that were in existence. This camera and associated studio was located on the top floor of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston at that time. This camera was very large and heavy, standing taller than an average man, with a folding bellows that extended out about six feet and a focusing glass that measured 20 by 24 inches, mounted on four metal wheels that gave it some slight mobility. Inside the camera was a long roll of twenty inch wide Polaroid film. After the artist had composed their picture the camera’s special operator pulled the rolled film down, (Literally like pulling down a window shade.) over the focusing glass, then he exposed the picture, cut off the print with an exacto knife, stripped off the backing, pinned it to a wall and let the print develop like any other Polaroid print.

Frank’s reason for coming to Boston was because he was participating in an experimental project where he had agreed to collaborate with three other photographers–Dave Heath, Robert Heinecken and John Wood– and my wife and me to collectively generate what we hoped would be an unusual exhibition and a book.

A few years earlier my wife Susie Cohen and I had worked on an exhibition with the photographer Todd Walker when he was teaching at the University of Arizona and I was working at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson.(2) Todd had the mandatory “Faculty Exhibition” at the University of Arizona coming up and was unhappy with the idea with simply putting his latest work on the wall in the traditional formulaic manner. Together, we worked out an exhibition format that displayed a number of finished works on a panel in the middle of the room and also displayed the trials, mistakes, second and third thoughts and variations to each of these pieces on the outer walls of the room. While some viewers were dismayed by the “clutter” of this exhibition, we all felt vindicated when a graduate student told Todd he had spent an entire eight hour day studying the works in the room and that he was going back again tomorrow. As the average viewing time of this type of exhibition, generously speaking, is probably less than an hour, we hoped and felt that we had shown a little bit about how an artist wrestles with and solves the visual issues that go into the making of their art.

Later Susie and I then began exploring ideas about using a traditional exhibition format to display more than just the finished art object; trying to think of ways of opening up that forum to a wider dialog about the artistic process and artistic decisions in general. In a very tentative way I mentioned some of these vague ideas to some friends, among them the photographers Robert Heinecken and, later, Dave Heath. As I was still very fuzzy on how to achieve these aims, did not have control of a gallery space or have any source of support for this type of project; these ideas still were very tentative at best. Nevertheless even the kernel of the idea was interesting enough for both Robert and Dave to be supportive. Then one day I received a call from Eelco Wolf, a Vice-President at the Polaroid Corporation in Boston, who had his own problem. Eelco had a history of supporting artists in a wide variety of interesting ways and he had initiated a project to help recover some rediscovered negatives taken by the photographer Lucien Aigner in the 1930s while working as a pioneering photojournalist in Paris. Aigner was now living in Western Massachusetts. Eelco had wished to develop an exhibition and catalog from this work, but the project had stalled from artistic difficulties with the eighty-year old artist. Carl Chiarenza had given Eelco my name, and he asked if I would help resolve some of the issues. I agreed to do so if he would listen to a proposition that I had about another project. I went to Massachusetts for a week and successfully worked with Mr. Aigner to put together an exhibition and catalog.(3) Then Eelco honored his word, listened to my very vague ideas about “capturing creativity on the wall” and then agreed to support the project.

The theory behind the project was that four mature artists would play an active role in determining both the content and the look of the exhibition by collaborating together as much as possible while my wife and I observed and commented upon the events. The exhibition was supposed to display the process of the creative act, rather than simply presenting the products of that act. In the early 1980s few well-established visual artists had collaborated together to any extent, as most pressures on them were to develop an individually unique visual style; and few exhibitions had been structured didactically to demonstrate process rather than product. We ultimately asked Robert Frank, Robert Heinecken, Dave Heath and John Wood if they would participate in the project. We had asked these particular artists because each one in their own way, by following their own vision, had contributed significantly to shift the nature and look of what was considered “creative photography” during their era; moving that look from the paradigm of a modernist, pre-visualized, single black and white print to the varied, multiple and vividly colorful look of creative photography in the 1960’s and 1970s.

During the next two years Susie and I met with these artists individually; first discussing the idea of the project with each of them and obtaining their agreements to participate and introducing, when necessary, their work to the others. Through this period my wife and I were interviewing, audiotaping, videotaping and photographing these meetings, then writing informal essays in a newsletter about these meetings to share with everyone else in the project.

We all then met as a group in Rochester, NY in April 1983 and in Boston, MA, over several scattered weekends during the first half of 1984 to further familiarize everyone with each other and to exchange ideas and refine the concepts and details of the proposed project.

First Meeting of the entire group in Rochester, NY. Row 1. Robert Heinecken and Robert Frank. 2. Nathan Lyons and Bill Johnson. 3. Joan Lyons and John Wood. Row 2. 1. Susie Cohen and Joan Lyons. 2. Joan Lyons and Robert Frank with camera. 3. Dave Heath photographing Susie Cohen.

Then the four artists spent a week isolated together in a house in Belmont, MA during the third week of June, 1984; visited only by the food caterers and Susie and me, to get to know each other better and further develop their ideas and conclusions about the look of the project. (Carl Chiarenza, who was going to write a foreword for the catalog, came over on one day; otherwise no one else disturbed the artists, nor did they leave that house.) The conclusion reached by the artists at the end of the week-long session was that each one would develop a sixteen-page signature for the proposed catalog/book that would accompany the exhibition.

Weeklong session in Belmont, MA. Row One. 1. Susie, Bill and Joshua on the lawn with Robert Heinecken. 2. Susie, Joshua with the cat and Robert. 3. Bill Johnson and Carl Chiarenza. Rows Two and Three. Evening session, Dave Heath displaying his work with Robert Frank, Robert Heinecken, John Wood, Carl Chiarenza and Bill Johnson observing and commenting.

The final phase of the project consisted of the artists creating their sixteen-page signatures while Susie and I wrote the texts for the catalog and then selected and organized the exhibition. The exhibition consisted of the original works they had created for the project plus a historical retrospective of selected works by each artist that demonstrated their own unique movement away from their inherited traditions of image-making. (The events were not quite as linear as described here, but basically it went that way. Much of my role in this event was trying to convince both myself and the others that I really knew what I was doing, when it was pretty clear that I didn’t. In any case the idea of displaying “Creativity” on a museum wall pretty much failed, mostly when I had failures in vision or of nerve and would fall back on traditional solutions and practices – which, after all, have become traditional because they handle certain problems very well.) Nevertheless, the artists were both intrigued and tolerant and some interesting things happened over the three year span and at the end, while we didn’t get “creativity” pinned down, an interesting –or so I and a few others thought — 400 to 500 print exhibition was put together that combined a partial retrospective survey added to the original works generated by the artists during the project. This exhibition was literally being framed up at the Visual Studies Workshop in Rochester, NY, the venue chosen to travel the show, and the catalog had been designed by Joan Lyons, and the final texts for the book were being written when a new President took over at Polaroid. Apparently he felt that the previous executive had allowed too much autonomy to his administrators and he cancelled the funding for this and a number of other creative projects that Eelco Wolf and some other officers at Polaroid had been engaged in at the time. So the entire thing was dismantled, the original photographs returned to the artists, and the other materials wound up in my closet. As the first usable desk-top computers became commercially available just as this project was being dismantled I concluded the project by publishing Horses, Sea Lions, and Other Creatures: Robert Frank, Dave Heath, Robert Heinecken and John Wood, by Susan E. Cohen and William S. Johnson. Belmont, MA: Joshua Press, 1986. 242 pp., 36 35mm slides bound in. Limited edition, 16 copies, printed on a IBM AT computer, with WordStar 2000 software. I distributed copies of this book to the participants in the project and placed a few in several institutional library collections.

“BOSTON, MARCH 20, 1985”

Although this project was supported and funded by Eelco Woolf, he had made no requirement that the artists use any Polaroid products in any of their work. But he did provide resources if the artists wished to use them and one of these resources was access to one of the two 20” x 24” Polaroid cameras in existence. Some of the artists chose to use this camera, others didn’t.

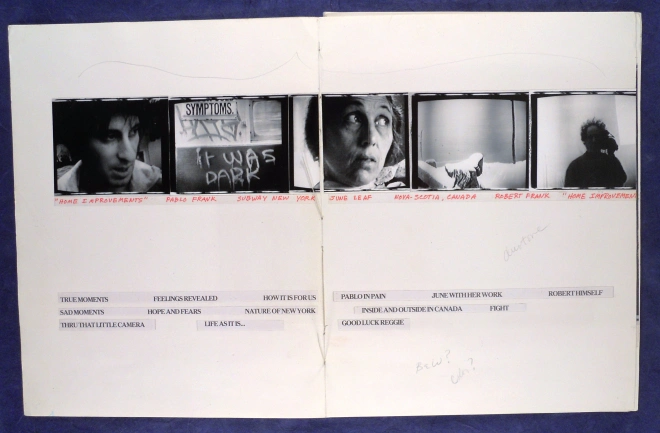

This finally brings us back to Robert Frank arriving in Boston in March, 1985. I picked him up at the airport and took him back to our apartment for dinner and to meet our ten month old baby boy, and to plan out his schedule for the rest of the week. All this background is necessary because while every artist in the “Polaroid Collaborative Project” made original work for this project, Frank also made work about the project, and that piece was the six 20” x 24” Polaroid panels that constitute the work entitled “Boston, March 20th, 1985,” which was created in the Polaroid studio in Boston the next day. (In fact Robert Frank made two multi-panel works in Boston that week, one for each day that he worked at the studio. The second work consisted of taking single-frame images from the videotape he had been making during the period this project was running and which he had shown to the group during the week everyone met together in isolation. This videotape, when finished, was released under the title Home Improvements. When Frank came to the point of creating his own sixteen-page signature he would reuse elements of these two works, plus a third sequence he had created in New York during the time the project was running, for his materials.)

The next morning Frank went to the studio with his paper bag full of litter, where he made the six still-lifes that constitute the work he titled “Boston, March 20, 1985.” Frank would later comment upon his making this work at a later seminar.(4)

“Robert Frank Workshop, Sunday, Nov. 6, 1988, 10:00 a. m.”

[Pinned to the wall are reproductions of several double-page spreads from four separate book layouts that Frank has created. Among them is the maquette for the sixteen page artist’s signature he created for the project. This maquette contained one ordering of the six panel work “Boston, March 20th, 1985.”]

“Robert Frank: Let’s start with the wall there and do the thing I hate to do the most, which is explain something….” “…I can say something about these big pictures here, that were all done in one day. I’m not used to working with another man, with a camera. I like to move the camera myself….”

[As I described earlier, the Polaroid 20″ x 24″ photographs are actually taken by a trained operator, who, at that time, was John Reuter.]

“So it was kind of difficult for me – I was uncomfortable working in the studio. I brought these things with me from New York to Boston, in the morning. It was a spring morning, I think. I brought the stuff with me – postcards, newspapers, and these frames that I bought on the street. In the old movie houses, where they changed the program every week, they stapled the new programs on the frames. So I brought about ten of those with me. And newspapers. And then I… I set it up, and I very, sort of impulsively, did the first one. When I got to Boston [the airport] there was one of these chauffeurs there, that pick up people. And he had a sign that said, “Mr. Kafka.” Well, I thought that was very good. So I wrote on a piece of photo paper, with developer, “Kafka.” And then, I had a contact sheet with me, and I wrote on it, “Spring.” I think it was the first day of Spring, that day. And then…here I said, “Good Morning.” Yeah, I wanted to put it together with “Kafka.” But I sort played around – I don’t know, it was really a still life. And then I worked with, oh, whatever I had. It had to do with [inaudible]…. And then I said, I’m going to talk about the other four [three] photographers. So then I started with this one, maybe Heinecken. I wrote on a piece of cigarette rolling paper with me – because I was probably a little bit stoned at that time – I wrote on it a saying that Heinecken made when we met up here.”

“He was always very interested in girls and he said he had to curb his lust. I thought that was a very good sentence. And I wrote it on the cigarette paper put it on each of these frames. That gave me the idea to make the other three or four panels for the other photographers. I took with me red and black paint, because that’s what I always use…”

[Frank is referring to the palm of his hand, covered in red paint, which he included in the Heinecken portrait. Frank has simplified the “Curb Your Lust” event, which was more nuanced and interesting in its implications, certainly within the project itself. See below.]

“So I always changed, the makeup of the way these rectangles [frames] were [inaudible]. At the end I was able to get the guy to move the camera outside, into the hallway. The last picture I did then, I wrote in it, “For David Heath,” I put myself in the back there, in the hallway. I liked this picture the best. And I always used the same motifs – the writing, that moved me, or a letter. It’s hard to explain. For John Wood, I did… well, I didn’t really know what to say about him, so I held up an empty piece, and said, “For John Wood.”

[During this exchange Frank kept referring to Johnson for specific details of the events, which caused him to comment at this point.]

“Its hard to explain… I have a merciful memory – it forgets…”

[Later, in response to a question from a participant in the seminar.]

“…When you have to work with the big Polaroid camera (referring back to the portraits of the artists in the Polaroid project) I still work with chaos. I know I have this camera for a day. If I would have been really conceptual, if I had a really clear working, thinking brain, I wouldn’t have needed to take all these different elements that make those pictures. I would have just taken these rectangles and put them up and on one I would have written “Heinecken” and on one I would have written “Frank” and on one I would have written “Heath” and that would have been it. Who needs all that other crap?”

[Referring to the newspapers photos, words, etc. that Frank pinned to the boards and photographed]

“But I don’t have that, so I had to do with it…. It was still planned – I took photographic paper with me and I knew I would write on it and it would become a certain way of writing by using developer on a piece of photographic paper. I knew the headlines interested me, I knew I liked postcards. And I just looked around the room and there was this picture a little print I have, that said “words” on it. So then I picked up the name Kafka by arriving at the airport. I mean, I work like that. It would be nice to be able to have a concept that was very clear, but it’s not my way. I would always change. I would always make a detour….”

SOME FACTS AND A LITTLE INTERPRETATION

The size and awkward nature of the manipulations of the Polaroid 20” x 24” camera meant that almost all of these large Polaroid prints, regardless of who the artist might be, were either studio portraits or still-life compositions. Frank had apparently decided to create a suite of metaphorical “portraits” of the participants in the project or, perhaps a bit more accurately, create a suite of metaphorical images of his responses to those individuals as he had come to know them through the project. As in any good metaphor, some of the meanings are susceptible to public interpretation, some are veiled in the artist’s own personal visualizations.

Frank has again and again insisted that he and his work is rooted in the immediate present. The six panels of “Boston, March 20th, 1985” demonstrate this. The hand holding the “Good Morning” sign in panel I is Susie’s. (Susie and I had decided to split the observation days and the baby watching days between us and she went to observe Frank on the first day. I brought the baby down to the studio at the end of the day to take everyone to dinner and I took some quick pictures. I observed more on the second day, when he made the “Home Improvements” group.) Frank later explained that the “Kafka” pinned to the cork-board in Panel I came about by his accidental sighting a person displaying a hand-lettered sign for “Kafka” waiting at the arrival gate at the Boston airport. This, and the fact that in his ordering of the six panels in the maquette that he developed for his sixteen-page signature he groups the first three panels together and then placed each of the last three panels on a separate page, leads me to believe that the first panel of the group is sort of an introductory comment about his being there and making the work then and there. I believe that Panels II and III are complementary, one referencing “Reality” or the world out there, with all its questions; and the other referencing “illusion” or the creative act, or the difficulties that an artist must confront when attempting to create his or her new reality. The hand holding the “Illusion” sign in panel III is Susie’s. That fact, plus the “Why” and “How” painted or scratched into the image leads me to believe that this is Frank’s referencing Susie’s and my participation and the unresolved nature of the form we were trying to find for the project’s exhibition.

Robert then places his own hand or body in the last three images, which are the “portraits” of his fellow artists. The hand holding the “March 20th, 1985. To John Wood” sign in panel IV is Robert’s, as is the hand covered with red and black paint in panel V. Frank later said that he had never got a good “reading” on John Wood in their meetings (John was a very quiet and reserved personality, and at most of these meetings he stayed in the background while observing everything closely.) and so he didn’t put much more than the date into that panel.

In Panel V, “For Heinecken” Frank references an event which had occurred at an earlier meeting of the group in Rochester, NY. Again, his “merciful memory” has simplified the event when he referred to it three years later at the seminar. I feel that Frank was intuitively referring to a much more complex and dramatic event in the course of this project in Panel V. The first meeting of all the artists together occurred in April 1983, where we met at Nathan and Joan Lyon’s house in Rochester to decide if everyone would agree to proceed with the project. (I had asked Nathan, the founder/director of the Visual Studies Workshop, to be the venue for the travelling exhibition when it was put together.) The artists were being asked to contribute their interest, time and energy for free to this rather vague and imperfectly articulated concept, with only the possibility of an uncertain and possibly even embarrassing exhibition in return. Each of the artists knew some of the other artists, and some knew Susie and me, but none of the artists knew all of the other artists personally; so there was a certain degree of checking out of everyone’s personalities and characters going on in addition to some measuring and judging of the value of the project itself; and the air was sparkling with small tensions all day. Then we all went to a long lazy lunch at a near-by café, where everyone socialized, told stories and attempted to become better acquainted and more comfortable with each other. As we ate and talked Dave Heath was circling the table shooting off pack after pack of SX-70 film, as intimate street portrait documents shot on the fly in the midst of everyday events with an SX-70 Polaroid camera was Dave’s mode of photographing at that time –. Dave would strip the Polaroid backing from the prints, stick the prints in his pocket and pile the litter onto the table. As the litter began to pile up on the table, Robert Frank, who had known Dave for years, and as a friendly commentary on what was happening, wrote “Curb Your Lust” on one of the peeled-off Polaroid backings, showed it to Dave and then placed it on the table. So the original “Curb Your Lust” was a reference to Dave’s lust to take photographs – and by extension, a semi-ironical recognition of every artist’s desperate desire to capture some true aspect of the world in his art. Then, Robert Heinecken, making a self-depreciating comment on his own sexual proclivities, (He was widely acknowledged in the creative photographic community both for daringly focusing his own art practice to comment upon human sexuality within the American culture — something not previously seriously dealt with within the photographic community– and also for his own well-known sexual encounters.) picked up the print backing with “Curb Your Lust” and slammed it against his forehead, where it remained stuck for the rest of the meal. I am attempting to describe all this in words, and I feel how clumsy my description is, and even accounting for my own lack of skill with words, how clumsy any verbal description of the event would be. What had just happened was a non-verbal, instinctive, wonderfully layered, commentary on artistic practice, on human passion, on the frailties of character, and the complexities of the human condition, by two major artists; all of which happened in a flash. In retrospect, I feel that it was at this instant that the group actually came together and everyone actually decided to go ahead and participate in the project.

The only photographer that Robert Frank had known personally before this project began was Dave Heath. They had both lived and photographed in New York City throughout the 1950s and 1960s, and both were part of the small underworld of “creative” photography practice that existed within the overwhelming weight of the reigning commercial professional photographic activity of that era. Dave was brought up as an orphan; for whom, I suspect, photography provided some form of salvation. At least, Dave brought far more than just aesthetic or professional concerns to his practice of photography, and I think Frank respected him for this passion. Panel VI “For Dave Heath” reflects both the somber and difficult internal landscapes which have been a part of Dave’s life; as well as Dave’s often acknowledged statements that the two strongest influences upon him as an artist were W. Eugene Smith and Robert Frank.

When Frank began to create the work “Boston, March 20th, 1985” his first decision was to wheel the 20″ by 24″ camera around so that it pointed out the door of the studio and into the narrow hallway adjacent to the room. This narrow hallway was lined with windows on the opposite wall. This simple act removed Frank from the box-like environment of a professional studio set-up and immediately altered both the dynamics of the situation and the visual and emotional spaces available to him. The controlled, ordered, organized spaces and lights of a typical studio set-up were suddenly replaced with a visual arena of clashing colder natural sunlight and the warmer artificial lights, in a space which was filled with cluttered and unfocused shapes, and with spaces and perspectives falling outside the camera’s expected range of operations. More than anyone else that I know who has used the Polaroid 20” x 24” camera, Frank had turned even the limitations of that system, its relative immobility and slowness and its shallow depth of focus, into positive tools to craft the emotional triggers he introduces into the images to generate their expressive meanings.

But more than that, Frank proceeded to subvert the traditional methodology of studio still-life photography in order to create the work he wanted, altering the dynamic of the traditional approach to producing “still-lifes” in this work. Normally this process is to assemble some objects in front of the camera until a pleasing “picture” is achieved, then to capture this achievement with the camera in what is, in essence, a document of a completed action. Frank altered this so that the creating of the “picture” became an active event in itself, a dialog between the artist and the camera, which is documented as it is played out in the space in front of the camera’s lens.

Frank has acknowledged his admiration for the New York School of action painters whom he knew in New York in the 1940s and 1950s. His motion pictures always reflect the accidents and happenchance of the instant that he is filming, even if there is a fictional narrative framework. His insistence that “Pull My Daisy.” was unscripted is more than an affectation, it is a declaration of intent, even a demonstration of an existential philosophy. He developed a photographic style that is visually focused on the urgency and immediacy of the instant; a photographic style which has had an enormous impact on several generations of photographers. And he has always, as I said, insisted that his art is always about his immediate present. When Frank began to assemble the cork boards and pin up pictures and papers, and began to mark, or letter, or paint words and comments on the assembled items he turned the photographic session into an active event, into which, from time to time, he paused to allow the camera to document the stages of its progress. He was documenting the action of making the art, rather than just the finished image. And as he decided to interpose humans or parts of humans (First Susie’s hand, then his own hand, then finally an out-of-focus self-portrait.) into the picture frame he was setting up a visual dynamic between the human figures, the written texts, and the objects within the picture frame –each kind of subject working upon a different type of psychological response from a viewer when viewing the image, thus keeping the viewer active throughout the process as well.

“Boston, March 20th, 1985” is in one sense a metaphoric portrait about the various individuals who were engaged in this project and of this artist’s reflections upon aspects of the small histories, however brief, these artist’s had shared. In another sense, the work’s self-referential tracing of the actual making of the pictures within the work is also a metaphor for the larger idea which this project had attempted to do – to “capture the act of creativity itself.”

ROBERT FRANK’S 16 PAGE BOOK SIGNATURE FOR THE COLLABORATIVE PROJECT.

NOTES

(1) This work is now held in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, and has been published several times. “Boston, March 20, 1985,” is reproduced on pp. 129-133 (folded panel) in Legacy of Light, edited by Constance Sullivan et al. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1987; on pp. 260-261 in Robert Frank: Moving Out, by Sarah Greenough and Philip Brookman, Washington: National Gallery of Art/Scalo, 1994; on pp. 206-207 in: The Printed Picture, by Richard Benson. New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2008; and elsewhere.

(2) … one thing just sort of led to another …The Photography of Todd Walker. (Nov. 18 Dec. 12, 1979). Museum of Art, University of Arizona, Tucson, Ariz. The Photographs of Todd Walker. With writings by William S. Johnson and Susan E. Cohen. Thumbprint Press, Tucson, AZ., 1979. 34 pp.

(3) Lucien Aigner’s Paris. (Dec. 1982) Text, bibliography, and preliminary picture selection by William Johnson. Stockholm: Fotografiska Museet, 1982. 104 pp. 75 b & w.

(4) In 1988 I was hired as Coordinator of University Educational Services at the International Museum of Photography at George Eastman House. I felt that a major aspect of the position would consist of coordinating and disseminating information for the photographic community in the Rochester area, so I gave first priority to establishing a desktop publishing facility and creating a publishing structure able to generate responsive, inexpensive documents — a facility not then available to the community. In 1988 I organized a semester-long seminar on Robert Frank and photography in the 1950s—60s, in which guest speakers lectured on aspects of the period and the artist throughout the semester, all of Mr. Frank’s films were shown at the George Eastman House, and at the end Mr. Frank spent a week-end workshop with the seminar participants, all of which was videotaped and transcribed. I then published this work in my series: Occasional Papers No. 2. The Pictures Are A Necessity: Robert Frank in Rochester, NY November 1988. Edited by William S. Johnson. Essays by Susan E. Cohen, Jan‑Christopher Horak, William S. Johnson, Tina Olsin Lent. Bibliography by Stuart R. Alexander. (Jan. 1989) 220 pp. This work consisted of re-edited texts on Frank previously published in Horses, Sea Lions plus additional texts relating to the seminar itself. I set this on a desk-top computer and then personally ran off two hundred copies of this 220 page work on the floor model Xerox machine at the George Eastman House. (This took several weeks, fitted-in between the museum’s secretaries’ photocopying needs.)

Dear Bill and Susie, Thanks for offering this terrific story while we ride out the storm called Sandy. I hope we can find someone out there who can publish Horses, Sea Lions. And please note that my middle initial is R and not A. The R is for Robert. All the best, Stuart

Hi Stuart,

How are you doing? There has been a stir of interest. Someone from an institution has approached me (You can probably figure out which one.), stating that they would put their fundraising efforts into an attempt to raise monies to publish this book if I was interested in doing so. As soon as I can find the time I intend to write a note to all the individuals involved to see if there would be any objections on their part. Everyone involved gave me verbal agreements to go ahead back then, but I didn’t get anything in writing and that was almost thirty years ago. Anyway, you will probably hear from me again. William.