FRANCIS BEDFORD (Aug. 13, 1815 – May 15, 1894) and WILLIAM BEDFORD (1846 – 1893)

BY WILLIAM S. JOHNSON

[THIS BIBLIOGRAPHY, FIRST POSTED IN 2012, WAS CORRECTED, REVISED AND EXPANDED IN 2023.].

Francis Bedford, born on August 13th, 1815, was the first son of the noted architect Francis Octavius Bedford, who had furthered the Greek Revival movement in the 1820s and the Gothic Revival movement during the 1830s as he designed at least nine churches which were built in London during that time. So Francis was immersed in the belief in the recovery of the historical past as a young man while he studied both architecture and lithography. He exhibited a drawing or painting of some architectural feature, such as “New Church at Turnstall,” (1833), “In Westminster Abbey,” (1846), “Canterbury Cathedral,” (1847) “Magdalen Tower, Oxford,” (1848), “York Minster,” (1849), etc., in the annual exhibitions of the Royal Academy at least nine times between 1833 and 1849. That he was well-versed in the history of architecture is clear from his articulate statement printed on the inside cover of his A Chart Illustrating the Architecture of Westminster Abbey. London: W. W. Robinson. [1846].

The immense flood of illustrated books, journals, pamphlets, and prints published in early Victorian Britain guaranteed a livelihood and a career for a young artist. By the mid-fifties Francis had brought together the talent, skills, and the network of editors and publishers, needed to establish himself as a lithographer skilled in illustrating journals and books specializing in architectural subjects, and he soon became widely regarded as a master in the chromolithographic process. The immense critical and public success in 1856 of Owen Jones’ The Grammar of Ornament. Illustrated by examples from various styles of ornament, with one hundred folio plates drawn on stone by Francis Bedford, cemented his reputation and then Bedford’s own The Treasury of Ornamental Art, (1857) and Art Treasures of the United Kingdom; from the Art Treasures Exhibition, Manchester. (1858) demonstrated Bedford’s further mastery of the medium.

Bedford began to photograph as an amateur sometime around 1852; taking up the new technology to aid himself in his lithographic work. His book, The Treasury of Ornamental Art, has been described as “probably the first important English work where photography was called into play to assist the draughtsman.”

But Bedford also began to pursue the creative aspects of photography as well. The 1850s was a period of enormous growth for photography in England. Frederick Scott Archer had just invented the wet-collodion process, and photography, though still difficult to use, suddenly became both more accessible and far more useful in a wide variety of ways. Archaeologists, anthropologists, botanists, geologists, art and architectural historians, scientists and learned men of every stripe were realizing that photography not only facilitated their studies, but that accurate, exact, and exactly duplicatable visual records made it possible to expand the dimensions of their respective disciplines beyond levels which had been impossible to reach before photography’s invention. Much of the leading research in chemistry and physics was being done by photographic scientists. Thus even conservative minds that could not decide whether photography was an art or merely a craft had to acknowledge that it certainly was a useful tool in the spread or diffusion of “useful knowledge” throughout the country, and agree in the role, both physically and metaphorically, that photographs played in support of the aims and needs of that generation.

The Great Industrial Exhibition held at the Crystal Palace in 1851, though considered a huge success, seems to have triggered a perception in England that it was in danger of losing its preeminent position as the greatest industrialized nation in the world. Driven by Prince Albert, a massive effort to expand education to the working classes and improve the scientific, industrial, and artistic knowledge of the citizenry of Great Britain was launched in the 1850s through the venue of newly formed semi-official organizations, such as the Society of Arts. The Royal Society of London formed the armature that tied the local and regional organizations to a centralized national level institution that could provide communications and other links across the existing divisions of class, education and culture. The Society offered organizational guidelines, provided discounts for book purchases for club libraries, provided knowledgeable lecturers on a wide range of topics, and toured traveling exhibitions useful for publicity and fund-raising projects.

Photography, widely described as one of the keystone scientific/artistic inventions that defined the modern age, provided one very powerful tool in this program. The medium, combining attributes of both art and science, still held an undeniable glamour, and was one of the most accessible and approachable of the new technological marvels. And photography played an extremely important early role in the activities of this Society and in its expanded educational mission. The Society sponsored the first hugely publicized and highly popular photographic exhibition in England. And the Society then became the parent organization for the Photographic Society, (later called the London Photographic Society and later still the Royal Photographic Society). The Photographic Society’s first exhibition displayed 1500 prints by many photographers; and this exhibition became a popular annual event. In addition to the large annual exhibitions in London, the Society of Arts also organized exhibitions of several hundred photographs which it traveled to many of the organizations of the Union, which, in turn, used these as a catalyst to organize lectures, or for fundraising soirees and fetes for the scores of Mechanic’s institutions and other adult educational organizations around Great Britain – and occasionally around the world.

Prince Albert and Queen Victoria played a leading role in fostering England’s arts, sciences and manufactures with their patronage and they supported the fledgling art/science of photography by purchasing creative photographs for their extensive art collections, by lending their public support to the newly formed Photographic Society, and by allowing access for selected photographers to their public lives.

In 1854 Queen Victoria and Prince Albert commissioned Francis Bedford to photograph art objects in the Royal Collection, an extensive task that Bedford performed admirably. Bedford exhibited some of these prints in the inaugural exhibition of the Photographic Society, held in 1854. Bedford, who had probably taken up photography as a tool to assist him in providing accurate and detailed renderings of the architectural subjects he was drawing, soon began to investigate its creative aspects, and this led him to taking landscape views,as was then a common practice for British amateurs interesting in the “creative” possibilities of photography. In the second exhibition in 1855, Bedford exhibited “many views from Yorkshire, bright and sparkling bits most of them, which we are only sorry to find so small.” This was followed by “The Choir, Canterbury Cathedral,” in the 1856 exhibition; and then by many well-regarded architectural and landscape views almost every year for the next thirty-odd years.

Queen Victoria purchased several of Bedford’s photographic landscapes from the Photographic Society exhibitions. Then in 1857 the Queen commissioned Bedford to secretly travel as her agent to Prince Albert’s birthplace in Coburg, Bavaria, to make a group of some sixty views as a surprise birthday present for the Prince Consort. Documents make it clear that Bedford was treated throughout this event as a favored guest, affiliated with the most powerful monarch in the world, and not as commercial tradesman performing a task. At this time Bedford also photographed the important “Art Treasures Exhibition” in Manchester to provide sources for his chromolithograph illustrations for the Treasures of the United Kingdom, published in 1858. This entire project had been fostered by Prince Albert as part of his ongoing support for contemporary arts and crafts practice in England.

Bedford’s social status as a gentleman in Victorian England helped define the range of opportunities available to him, and along with his undoubted talent and drive, structured the expansion and development of his career as he transitioned, as had a number of his contemporaries, from an amateur into a professional photographer; earning his living and eventually building a business empire that made him into a wealthy man.

Francis Bedford used the wet plate process throughout his entire career, well after various dry plate processes were available to photographers. By 1857 Bedford was being mentioned by various critics as one of the premier landscape photographers in England, a reputation he maintained throughout his lifetime. As one critic defining the accepted standard of quality for a good picture maker at that time, stated “… A happy choice of subject, skill in the composition of their picture, due attention to contrast of light and shade, and to gradation of distance and atmospheric perspective; but we think that we see in Mr. Bedford’s works the most complete union of all the qualities which must be united in a good photographic picture.”

After Roger Fenton retired from photography in the early 1862; his mantle as the leading landscape photographer was taken up by Bedford. By 1865 “Bedford” is one of a handful of names that is routinely used by critics or writers as an example to denote high-quality and creativity in photography. Thus, as the British were believed to excel in the genre of landscape views, Bedford was considered to be one of the best and certainly one of the best-known photographers of the day.

Furthermore, his name became associated with the continuing struggle among photography’s advocates to have the medium accepted as a high art practice. “…For photography, then, in both facts and theory, we have able advocates, and ultimately the rank it claims must be awarded to it; and I trust, when that day comes, we shall not forget the pioneers without whom such crowning honour and distinction might never have been obtained. Of what use would be my assertions or arguments, or those of “any other man,” if we could claim no Rejlander, no Robinson, no Lake Price, no Bedford, and no Wilson? Who would have dared, in the absence of their works, to make for photography the claim now occupying our attention?”

Wall, Alfred H. “In Search of Truth.” British Journal of Photography 10:194 (July 15, 1863):285-286. [“Read at a meeting of the Edinburgh Photographic Society, July 1st, 1866.”]

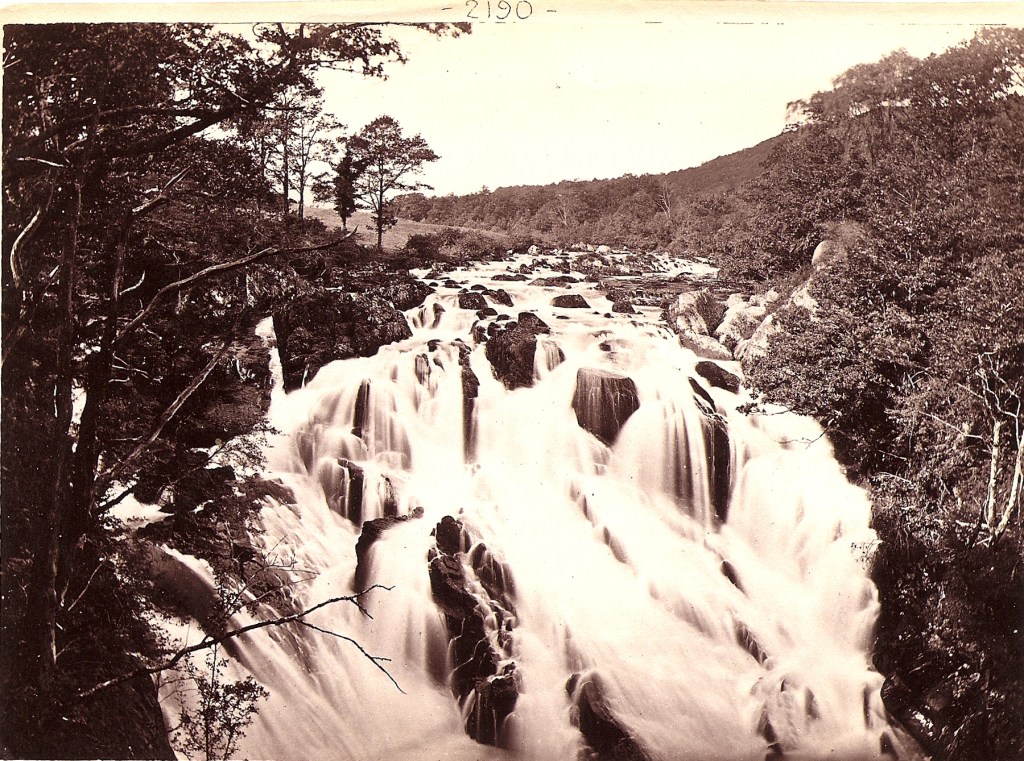

In 1859 Bedford traveled through North Wales making landscape photographs and stereo views, which he released commercially in the spring of 1860 through the publisher Catherall and Prichard, of Chester. “…The series of the latter is large, and comprehends a considerable number of the leading objects which excite the wonder and admiration of tourists, and have been the special delights of artists time out of mind. The photographs are of good size, and it is scarcely requisite to say, are of the highest possible merit, — the name of Mr. Bedford will sufficiently guarantee their excellence. …The stereoscopic views are certainly among the best that have been produced, supplying a rich intellectual feast: to us they have given enjoyment of the rarest character — and so they may to our readers, for they are attainable at small cost. We name them at random, but they are all of famous places — Pont Aberglaslyn, Capel Curig, Llyn Ogwen, Bettys-y-coed, Beddgelert, Pont-y-gilli, Trefriew, Llanberis, Pen Llyn, with views also of the Britannia Bridge, Carnarvon Castle, &c.” (Art-Journal, Apr. 1860).

“When Francis Bedford, that prince of the early landscape photographers, began, in 1858, under the auspices of a Chester firm of publishers, to do for large districts what the local photographers had hitherto done for their own little domains, he soon found that first-rate pictorial work had little commercial value. He began with Wales, and afterwards annexed other regions. His work at that time consisted almost entirely of stereoscopic slides, and the imperative demand of the travelling public was that they should be “clear,” and this great artist had to manufacture the article to order. Every item of the view, from the stones in the near church or chapel to the distant mountains, had not only to have all the boldness and definition to be obtained in the clearest weather, but had to be helped by those subtle devices of which he was a master.

Besides the stereoscopic slides—it would be difficult to convey to the modern photographer any idea of the immense number sold in those primitive days— Bedford occasionally made larger pictures to suit his own cultivated taste, which were the delight of our exhibitions, but had no interest for the general public, who at that time were sufficiently satisfied with the miracle of definition photography continued to present to their still wondering senses, and who had no eyes for higher qualities. I mention these pictures to show that the fault lay not in the artist, but in his patrons. Although the work manufactured for the tourist had to be suited to the bad taste of the buyers, it was always the best of its kind. The best points of even poor subjects were selected with curious skill; there were few figures admitted in those days of long exposure, but when they were allowed to appear they were in the right place, admirably posed; they were always the addition wanted to make a picture, not the accidental crowd of figures in the wrong place that instantaneous exposures usually present to us.” (Robinson, H. P. “Rambling Papers. No. XXXI. — Local Views.” Photographic News 39:1922 (July 5, 1895): 424-426.)

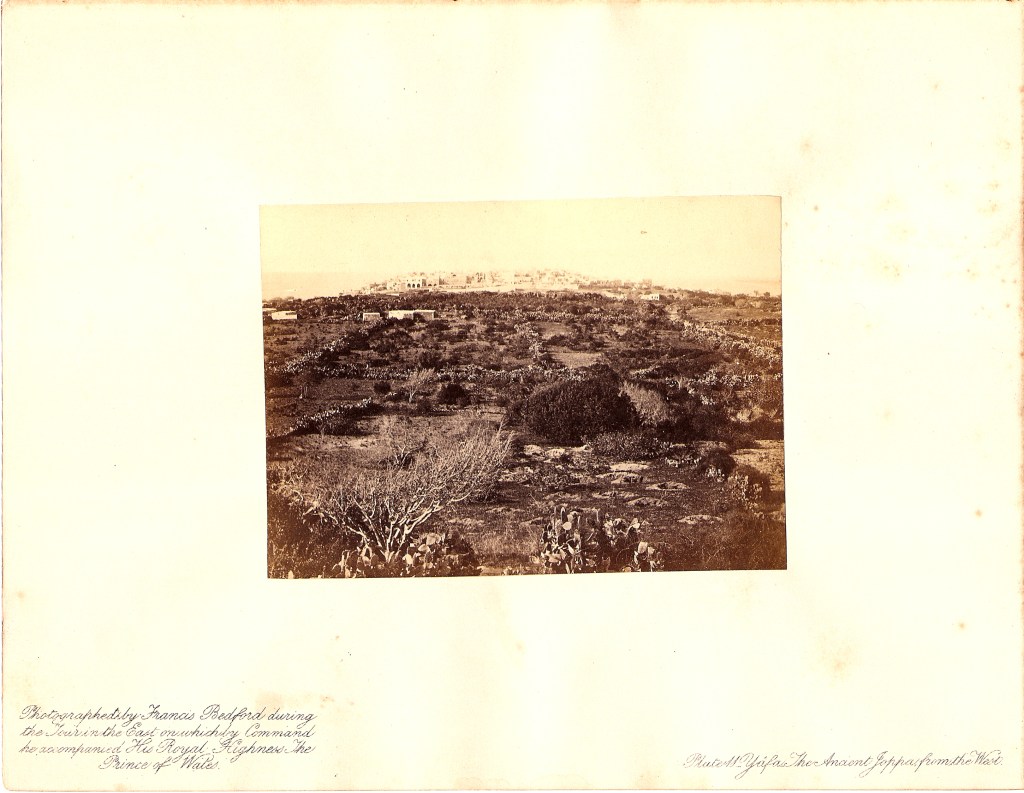

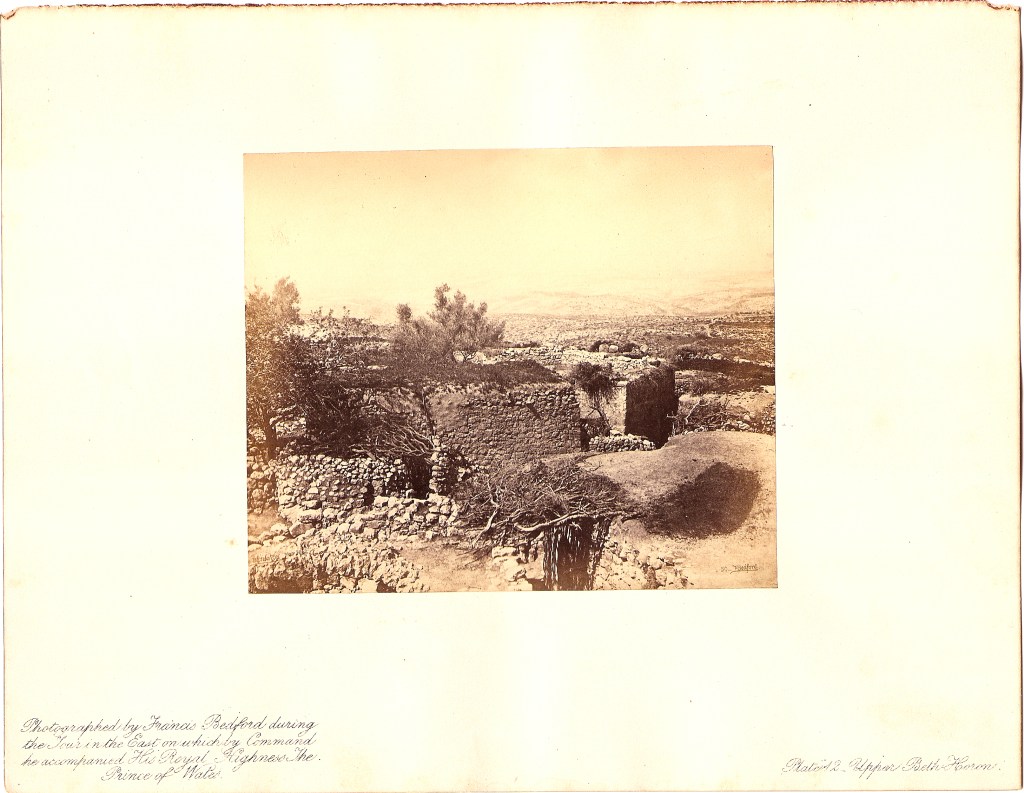

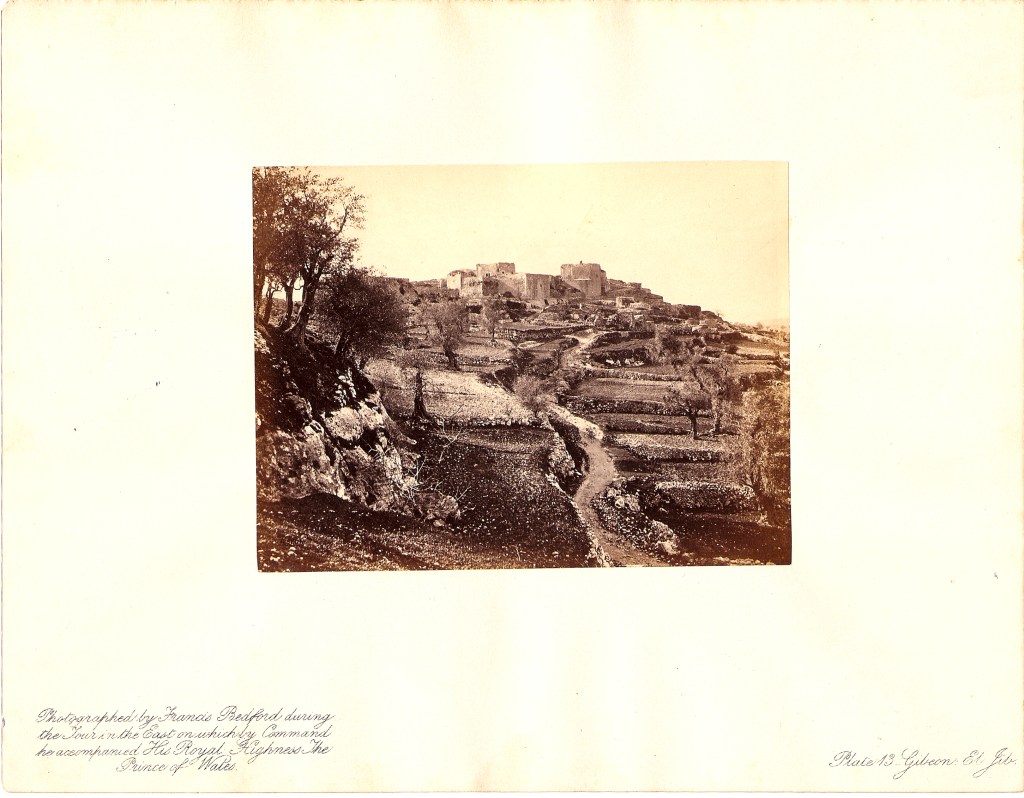

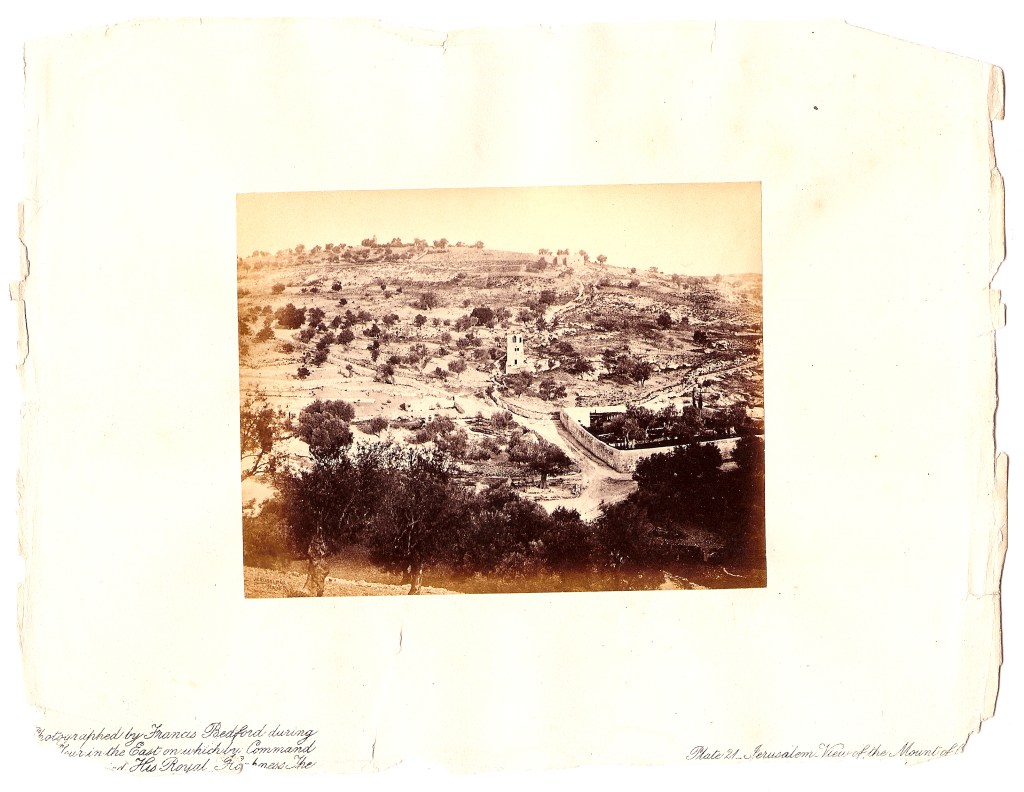

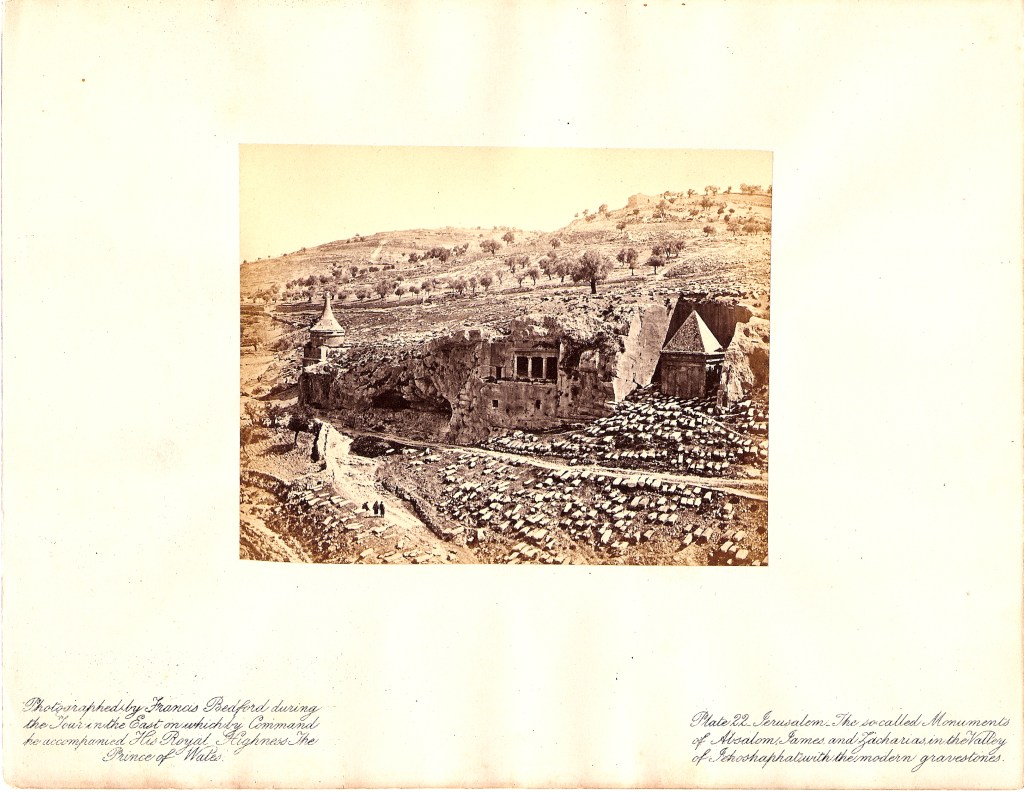

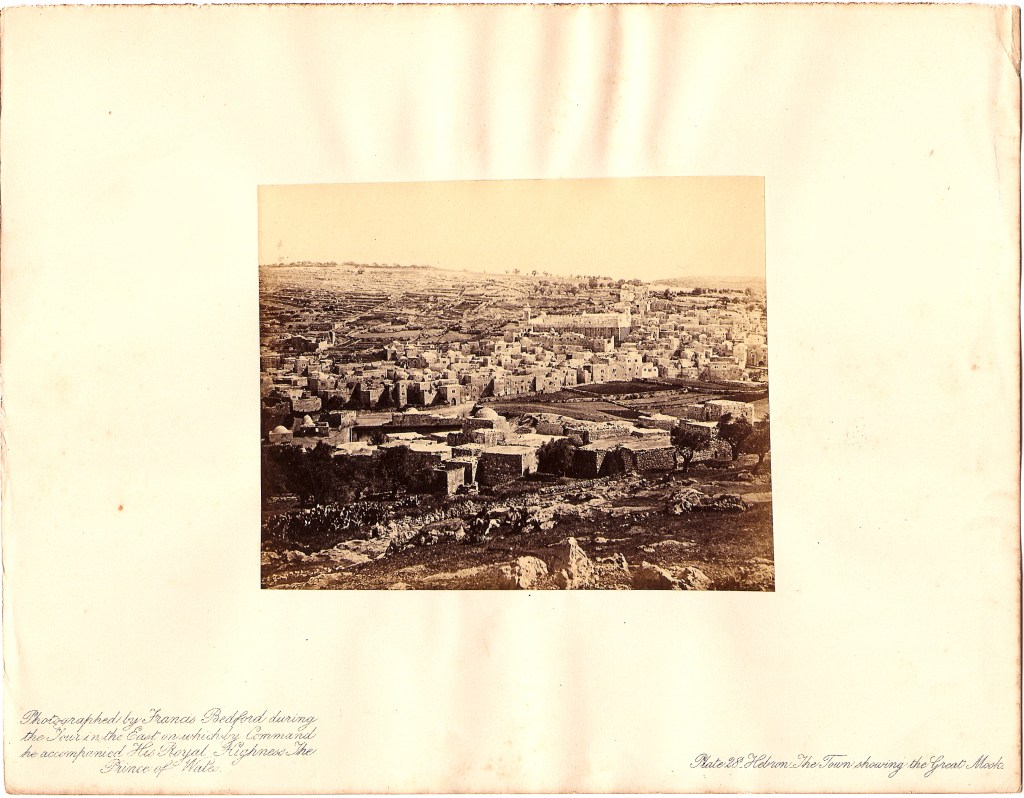

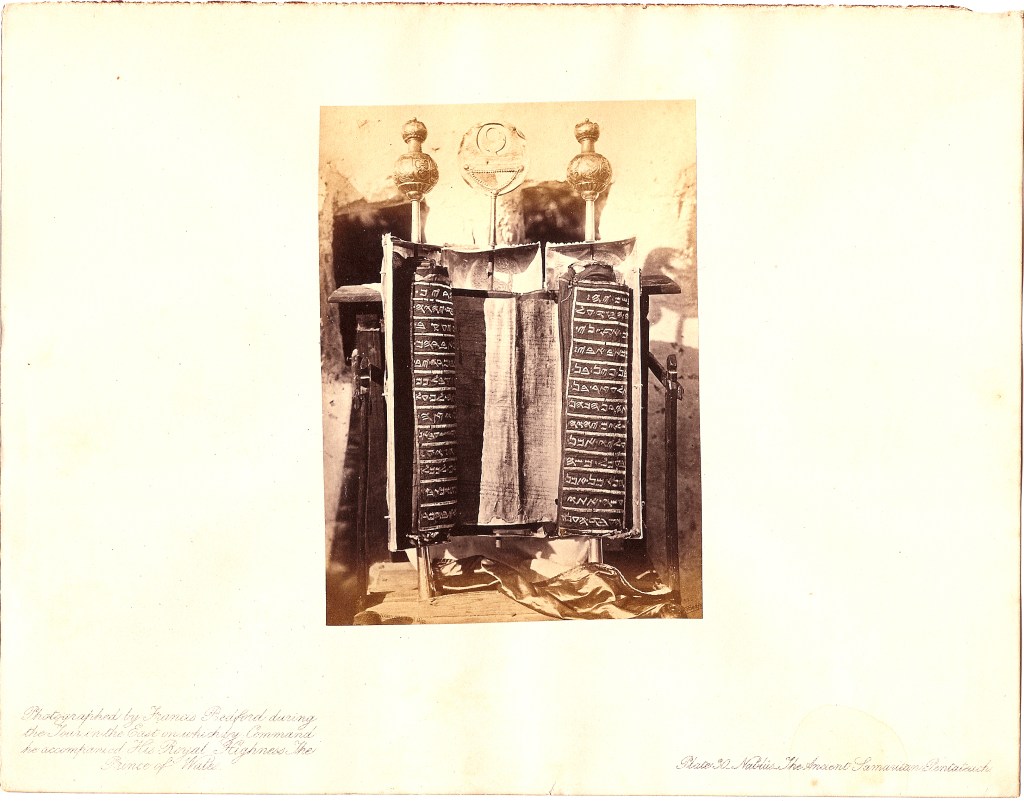

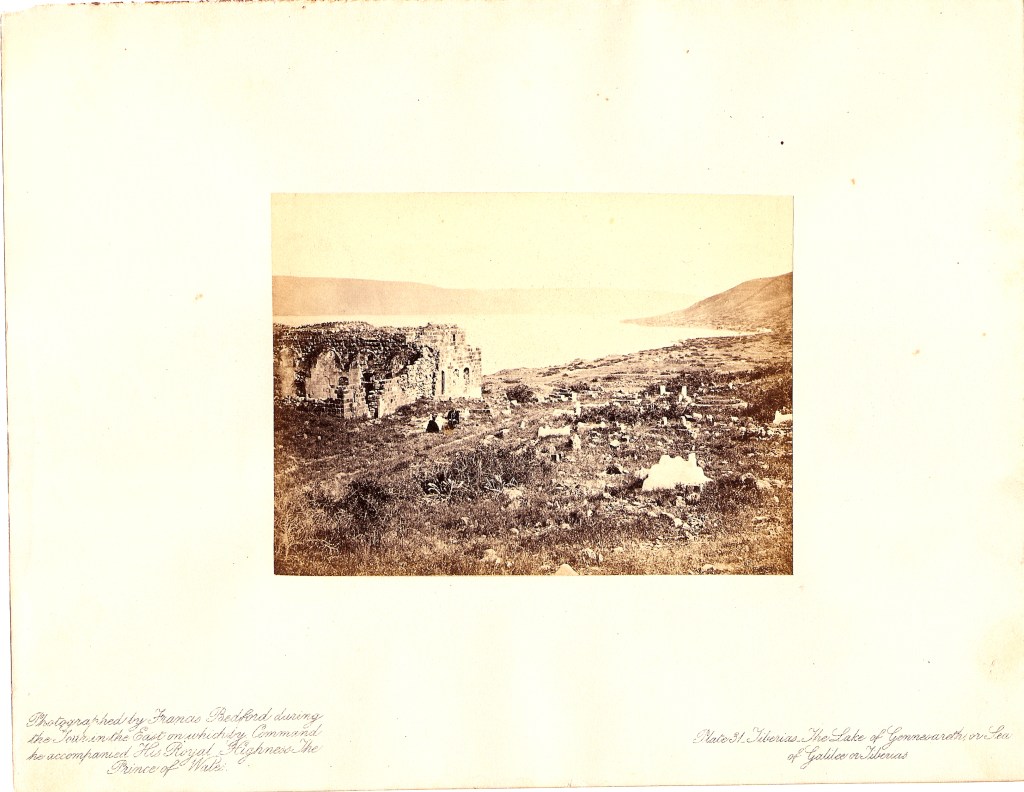

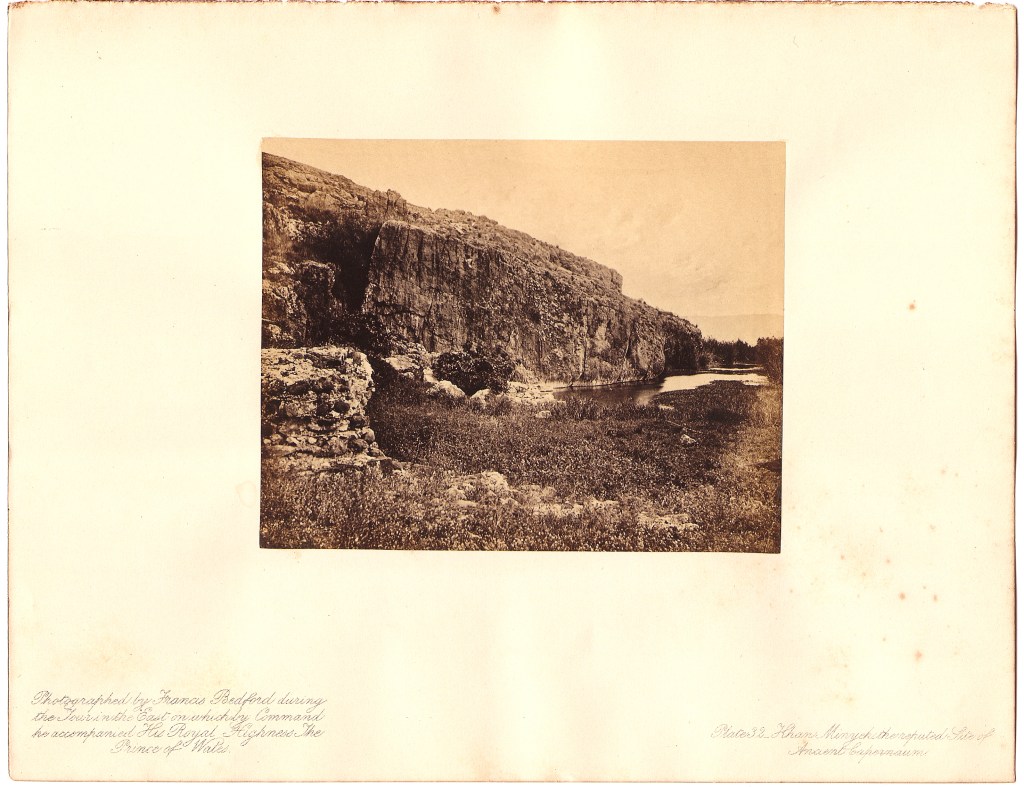

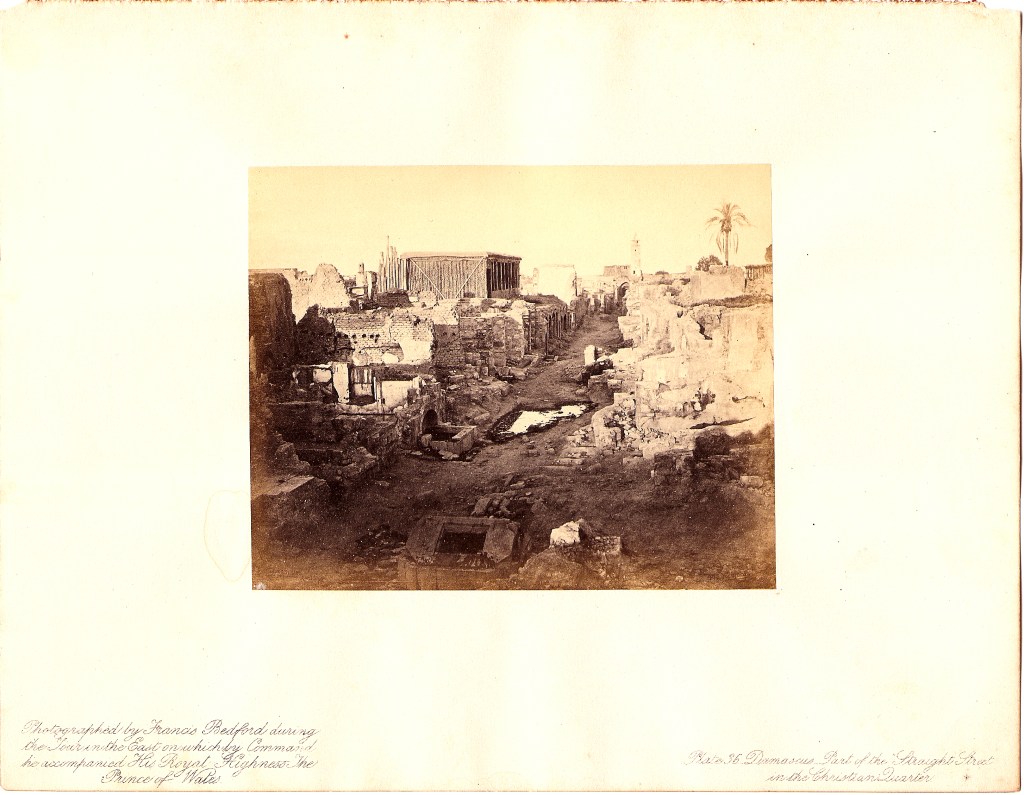

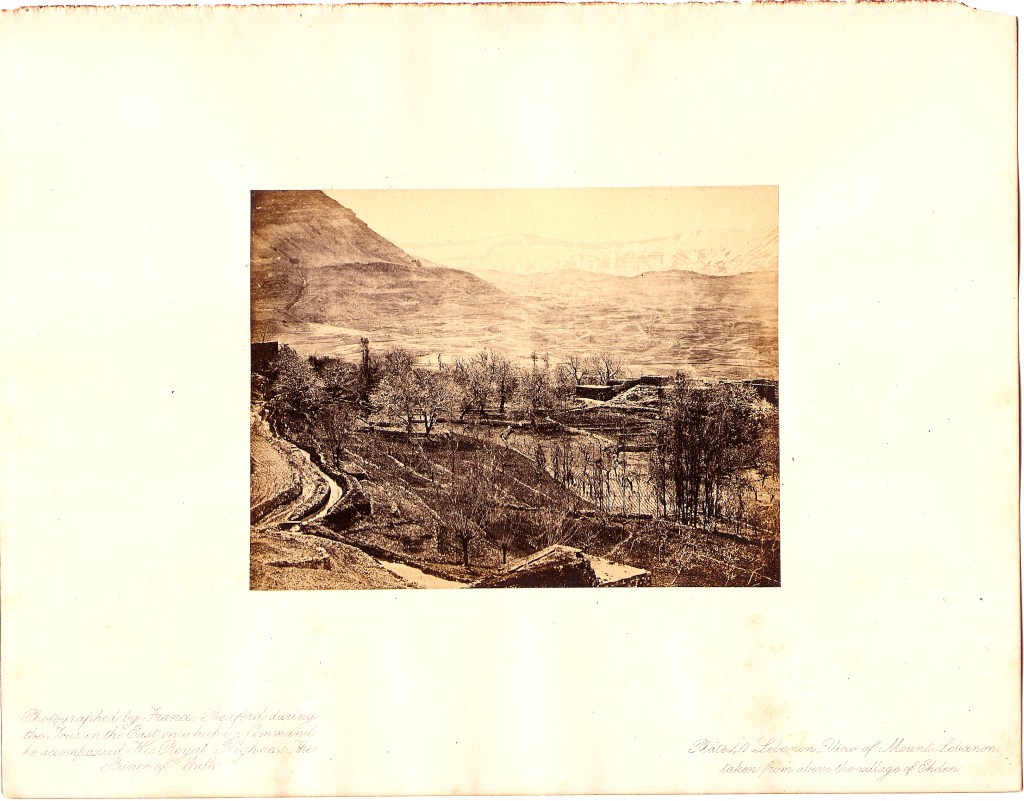

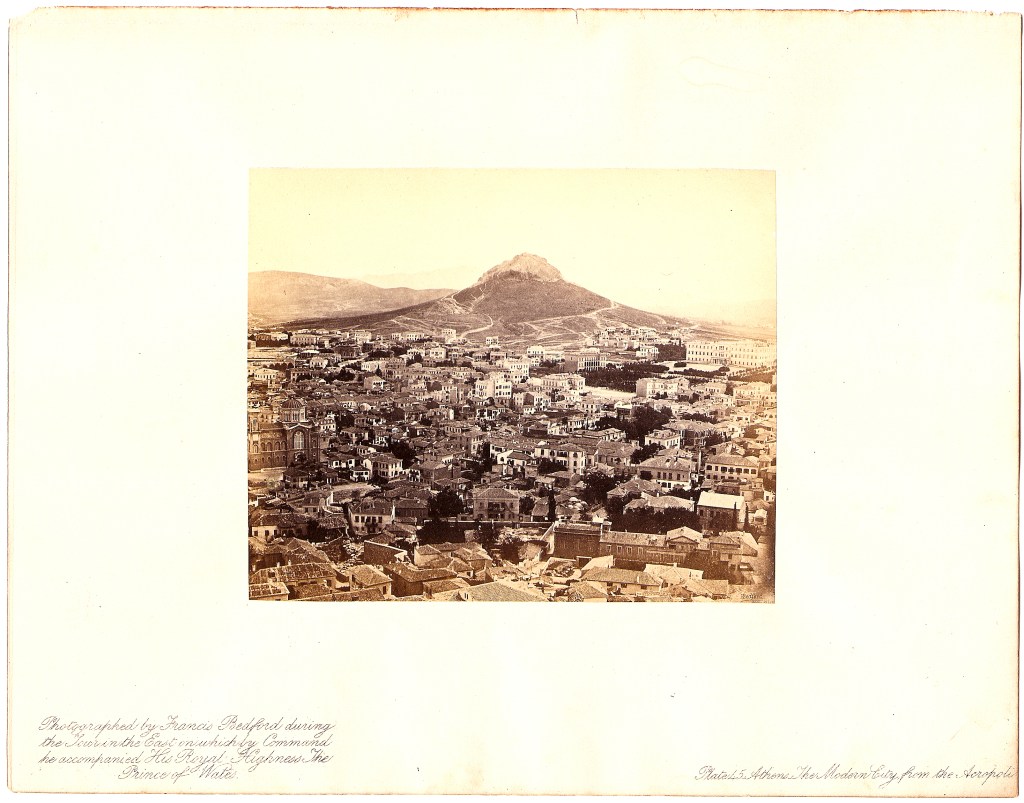

In 1862 Bedford’s strong position with the Royal Family was demonstrated again when he was “one of only eight gentlemen” invited to join the Prince of Wales (the future king of England) on a four-month tour of the Near East. Bedford made about 210 views on this trip. The trip was followed avidly by the British press and a number of Bedford’s photographs were published (in woodcut form) in the London Illustrated News and elsewhere throughout 1862 and later. Bedford also had a one-man exhibition (Still an unusual event at the time.) upon returning to London. The immense prestige garnered by Bedford through these activities buttressed his reputation as one of the leading landscape photographers of the day, both within the photographic community and in the minds of the general populace as Bedford became one of the handful of photographers who was widely recognized outside of the photographic community.

Day & Son, “Lithographers to the Queen, Illustrated, Illuminated, & General Book & Fine-Art Publishers,” who had published Bedford’s earlier chromo-lithographic work, published in 1863 the three volume Photographic Pictures made by Mr. Francis Bedford during the Tour in the East, in which, by command, he accompanied H. M. H. the Prince of Wales, which contained 172 original photographs. This effort was somewhat marred by the fact that Day & Son, one of the largest and most prestigious art publishers of the era, went into liquidation in 1868 and their stock was sold off and broken up in a series of auctions throughout the year. They still held several hundred copies of Bedford’s Egypt,…, the first volume of this publication, in stock and the fact that Bedford’s book was one of the dozen or so titles featured throughout the auction descriptions throughout the year indicates the prestige value placed upon the work. Originally priced at a luxurious 2l. 2s., the work was resold and eventually remaindered for 14s. 6d. per copy. This at least had the effect of making his work accessible to a larger number of people, although to truly succeed as a commercial landscape photographer at that time one had to work as a stereo view maker.

Francis returned from the Near Eastern tour to again begin photographing landscape views in England, focusing his interest in the south-west of England and the West Midlands, while going again and again to his favorite sites in North Wales and Devonshire, which he photographed almost annually from 1863 until at least 1884. Previously Bedford had focused on taking photographs and leaving the complex process of commercial scale printing and distribution through other established publishing sources, but at some point soon after his return from the Near Eastern tour Francis Bedford established his own company for producing the popular stereo views, and the company flourished and grew to be one of the three or four largest producer of stereo cards through the remainder of the century – making Bedford a very wealthy man.

Throughout the 1860s the many large national or international exhibitions, (Some displaying thousands of photographs and seen by scores of thousands of visitors.) provided a major venue for photographers. Bedford diligently participated in the annual Photographic Society exhibitions, the Edinburgh Photographic Society exhibitions, the international expositions in London in 1862 and in Paris in 1867, and in many other regional exhibitions in Great Britain and in Europe, almost always winning awards and the usual degree of high praise for his landscapes.

Francis Bedford was elected to the Photographic Society of London (now the Royal Photographic Society) in 1857? and then elected a member of Council to that organization in 1858. In 1861 he was elected Vice President of the Photographic Society, a position of great prestige. Bedford was active in that organization, periodically serving as one of the Vice-Presidents or as an officer on the Council off and on for the next thirty years. F. Bedford is listed as Vice-President during the years 1863 to 1868. During 1866-1867, Francis Bedford, serving as a Vice-President, chaired five of the monthly meetings, provided the negative for the annual “presentation print” which was distributed to the membership, and participated in the annual exhibition. Frequently, when he was not serving as a Vice-President he served on the Council. F. Bedford is listed on the Council in 1858 to 1861, and from 1871 to 1888. These were rotating positions, renewable each year in theory, and Bedford was voted into them again and again. In fact, Francis is not listed as an officer of the Society between 1858 and 1888 only during the years 1869 and 1870. His son William Bedford was elected to the Society in Feb. 1870, voted to the Council in 1877 and for many of those years joining his father on the Council from 1877 to 1888; and serving thereafter on his own until his death in 1893. During this period The Photographic Society of London (later renamed the Photographic Society of Great Britain) held an important place in British photographic practice and the lectures and exhibitions held by the organizations often defined the most creative, most vital and important aspects of the medium.

Both father and son seemed to be well-respected, and both seemed to provide a moderate, stabilizing and beneficial influence on the activities and actions of the Society during the thirty years of their presence. Both Francis and William Bedford had also been members of the North London Photographic Association during the 1860s. “…The Council notice with regret the dissolution of a useful, and at one time active, auxiliary of this Society which has existed for more than twelve years in the metropolis, under the title of the North-London Photographic Association.” (Photographic Journal (Feb. 16, 1870): 198.)

When this “auxiliary” organization folded, Francis seems to have once again played a more active role in the Photographic Society of London, and William was elected to the Society in February 1870. By 1876 Francis is back on the Council again. This is the year when William seems to blossom, winning a great deal of praise for his landscape views in the annual exhibition, including the statement that his work “…shows that the mantle of the father has fallen upon the son.” In 1878 both father and son were still active participants in the Society, the son, on the Council again, organizing many of the tasks of that group, and the father again elected to a Vice-Presidency to fill a sudden vacancy in the organization. Both Francis and his son William were still displaying landscape views in the annual exhibition in 1878, but by the late 1870s, with Francis reaching into his sixties and having achieved universal acclaim, the weight of the activity seems to have shifted from the father to the son. Francis also contributed liberally to local photographic societies exhibitions and events throughout the United Kingdom during these years.

“From this time until 1884, (Francis was 68 years old.) when he relinquished his business to his son William, he went annually to the country to take fresh negatives, chiefly in North Wales and Devonshire. He had two children, Arthur, who died in 1867, and William, who died in 1893, and whose departure and merits are still fresh in all our memories. The wife of Francis Bedford died in 1888; this was a great blow to him, and long preyed upon his mind. He was extremely painstaking in his work. Once he waited at Lynmouth for a fortnight to get a required satisfactory pictorial effect at the time of high tide. He had certain standards of his own, and when either negatives or prints did not come up to those standards, he destroyed them ruthlessly. He was a great hater of crowds, disliked photographing even in small villages; he preferred solitude, and loved the mountain and the moor in their wildest aspects; he said that in the midst of such scenes he looked up from nature to nature’s God. He was also partial to quiet scenes in country lanes. He was never of strong constitution, and many in his place would have given up work earlier; however, he did not do much actual hard work himself, but he directed everything. He was of a retiring disposition, exceedingly courteous in his manner, he was also considerate and kindly to those who worked under him. He was slow to make friends, but when he made one the friendship was true and lasting. He was pure in thought and speech, and retained all his mental faculties until the last moment.” (Photography: The Journal of the Amateur, the Profession & the Trade (May 31, 1894)

PORTFOLIO OF VIEWS

In 1859 Bedford traveled through North Wales making landscape photographs and stereo views, which he released commercially in the spring of 1860 through the publisher Catherall and Prichard, of Chester. Bedford went to the West Midlands, visiting his favorite sites in North Wales and Devonshire, which he photographed almost annually until at least 1884. These stereo views were issued in series, “North Wales Illustrated Series,” “Devonshire Illustrated Series,” etc., throughout his lifetime, and in some cases these series consisted of two to three hundred images.

“The names we have just written in juxtaposition, North Wales and Francis Bedford, will suggest at once to most of our readers some very lovely and picturesque stereographs: glorious scenery and perfect photography combined. Abounding with views pre-eminently adapted to the stereoscope. Wales has been a favourite resort with landscape photographers and its scenery has been done in almost every style. Who for instance, is not familiar with the Rustic Bridge at Beddgelert? But how few have obtained such a picture as this before us, No. 174 of the series? Nothing could more forcibly illustrate how far the photographer may also be an artist than these pictures, and the taste, judgment and feeling of the beautiful which has regulated their selection. …” “Critical Notices.” PHOTOGRAPHIC NEWS 4:120 (Dec. 21, 1860): 400-401.

DEVONSHIRE ILLUSTRATED SERIES

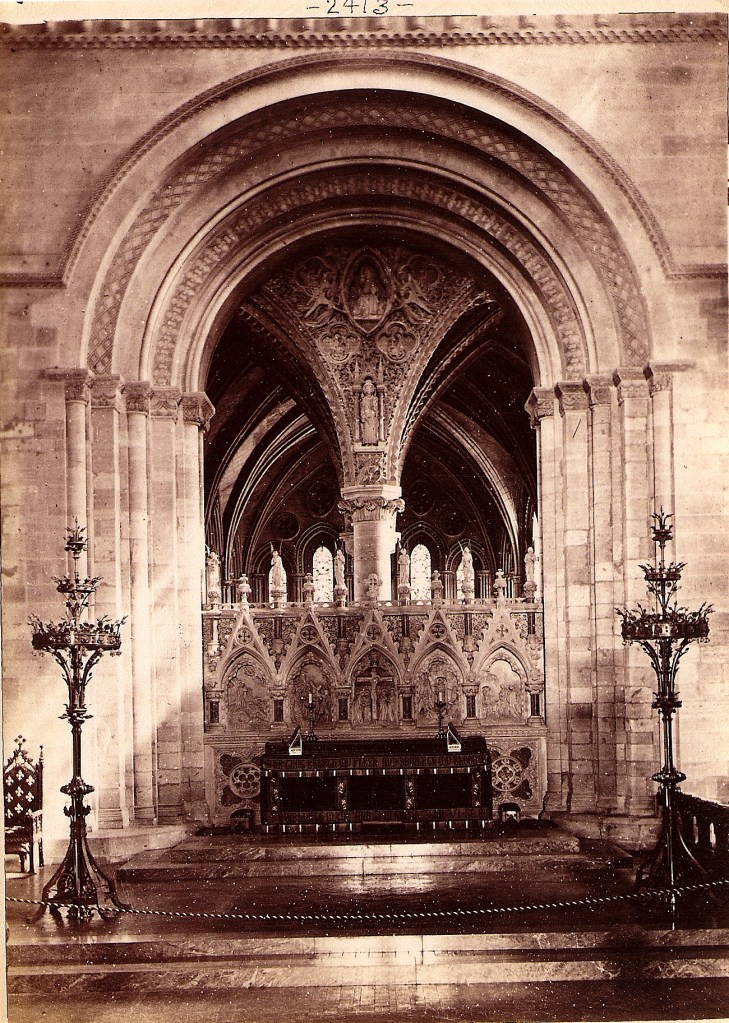

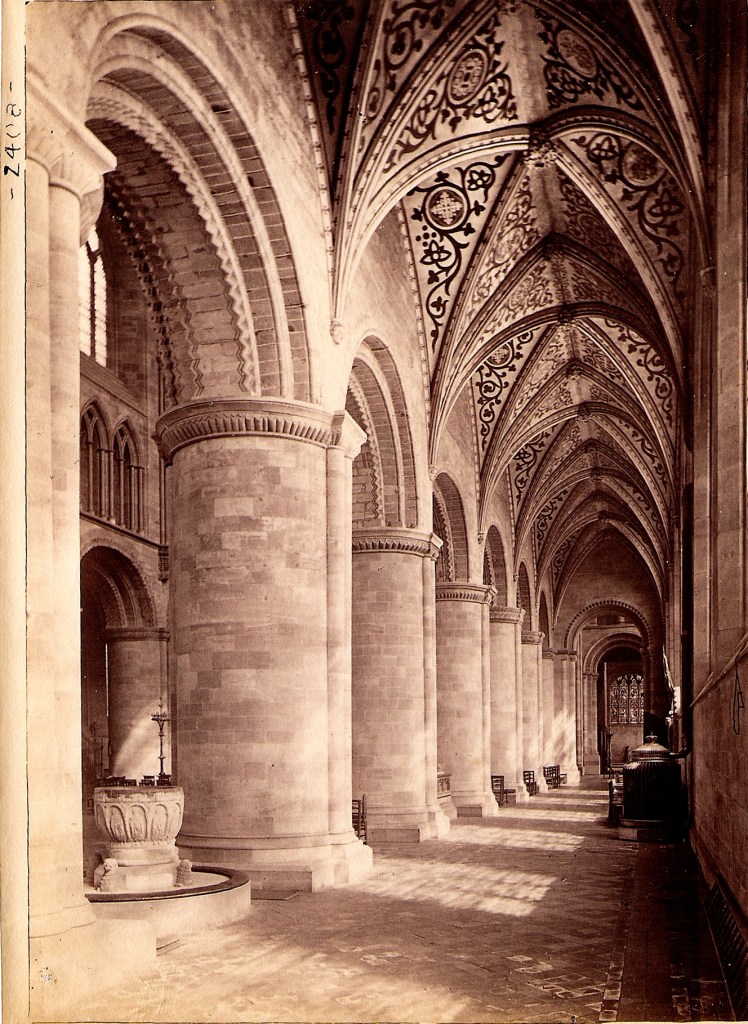

“…In all this Exhibition there is no man’s work, take it all in all, comparable, in our opinion, to Mr. Bedford’s, whether it be of subjects architectural—as his interior views of Wells Cathedral and his exterior subjects from Exeter Cathedral—or natural, as the rocks we have referred to. and other Devonshire scenes. Besides other merits, Mr. Bedford seems to us to have carried the perfect rendering of reflected lights and half tones further than any of our photographers. This is the crux of photographic art. Nothing can be conceived more delicate than the gradations from highest light to deepest shadow in the Ilfracombe subject; nothing fuller of aerial effect than the bit of the Chapter-house vestibule, Bristol. Mr. Bedford appears to us to show peculiarly sound judgment in his selection of subjects….” The Times, January 18, 1861.

“Criticism on the Exhibition.” PHOTOGRAPHIC JOURNAL, BEING THE JOURNAL OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC SOCIETY. 7:106. (Feb. 15, 1861): 116-117.

GLOUCESTERSHIRE, ETC.

“When Francis Bedford, that prince of the early landscape photographers, began, in 1858, under the auspices of a Chester firm of publishers, to do for large districts what the local photographers had hitherto done for their own little domains, he soon found that first-rate pictorial work had little commercial value. He began with Wales, and afterwards annexed other regions. His work at that time consisted almost entirely of stereoscopic slides, and the imperative demand of the travelling public was that they should be “clear,” and this great artist had to manufacture the article to order. Every item of the view, from the stones in the near church or chapel to the distant mountains, had not only to have all the boldness and definition to be obtained in the clearest weather, but had to be helped by those subtle devices of which he was a master. Besides the stereoscopic slides—it would be difficult to convey to the modern photographer any idea of the immense number sold in those primitive days— Bedford occasionally made larger pictures to suit his own cultivated taste, which were the delight of our exhibitions, but had no interest for the general public, who at that time were sufficiently satisfied with the miracle of definition photography continued to present to their still wondering senses, and who had no eyes for higher qualities. I mention these pictures to show that the fault lay not in the artist, but in his patrons. Although the work manufactured for the tourist had to be suited to the bad taste of the buyers, it was always the best of its kind. The best points of even poor subjects were selected with curious skill; there were few figures admitted in those days of long exposure, but when they were allowed to appear they were in the right place, admirably posed; they were always the addition wanted to make a picture, not the accidental crowd of figures in the wrong place that instantaneous exposures usually present to us. The mounting, as well as the general get-up, was fastidiously careful. All this was art of a kind as far as circumstances would allow….”

Robinson, H. P. “Rambling Papers. No. XXXI.- Local Views.” PHOTOGRAPHIC NEWS 39:1922 (July 5, 1895): 424-426.

HEREFORDSHIRE ILLUSTRATED SERIES

“The Monthly Meeting of the Members of this Association was held at the Myddelton Hall, on Wednesday last, the 4th inst. W. W. King, Esq., in the Chair….” “…The Chairman then read a paper “On Architectural Photography.”

“It must be generally conceded that architectural photography has attained a position of greater prominence in the science than any other branch thereof, and this for two very good reasons:-—first, that the subjects themselves are not liable to be affected by wind, that enemy to photographers—so dangerous, indeed, that Mr. Jabez Hughes, in his excellent little work, advises the reader never to photograph on windy days; and, next, that the subjects possess a permanent interest from their clear individuality. Landscapes, beautiful as they are, cannot successfully compete with them in this respect, for one beautiful view may be exceedingly like another: we pass it by in our portfolios and think but little more about it. But the representation of a piece of architecture is altogether different. There the photograph appears to the greatest advantage: we at once recognize the building, and can, if need be, identify every stone or saint whose sculptured effigy adorns a niche or pinnacle. The building is seen from a point of view known and, therefore, familiar to all. We turn to the photograph again and again with renewed pleasure; for it forms a record of authority and weight. The architectural profession has not been slow to appreciate the value of photography, and the public themselves, now that archaeological and art knowledge are being more diffused, and taste somewhat improved, delight in the beautiful reminiscences of our ancient buildings. I think I may say that our countrymen are far in advance of any other nation in dealing with architectural and archaeological photography. Go to one of our photographic exhibitions, and you are sure to see some of Mr. F. Bedford’s exquisite productions, showing his possession of something more than a mere knowledge of photography—namely, a true appreciation of, and love for, the art works of our forefathers….” * * * * * The superiority of modern English ecclesiastical architecture must be generally admitted, from the greater love for old works which our architects evince by their works; and we see why architectural photography of ancient remains should be more practised in England than in France. I think we may say that the photographs of interiors at the present time leave little or nothing to be desired. I must refer again to the honoured name of Mr. Bedford and to Mr. Good. Their works show the advance which has been made in photographing the interiors of our cathedrals and churches, as do also the stereoscopic slides by the other photographers I have named. Of course, photographers, as a rule, will take subjects which are most popular, those most known belong to that class; for it is nothing more than a mere truism to say that people will patronize things known, though they may be ugly, rather than a beautiful object which they have not seen. Still, it is a great thing to have some old objects from a new point of view….” “North London Photographic Association.” PHOTOGRAPHIC JOURNAL, THE JOURNAL OF THE PHOTOGRAPHIC SOCIETY 12:188 (Dec. 15, 1867): 152-155.

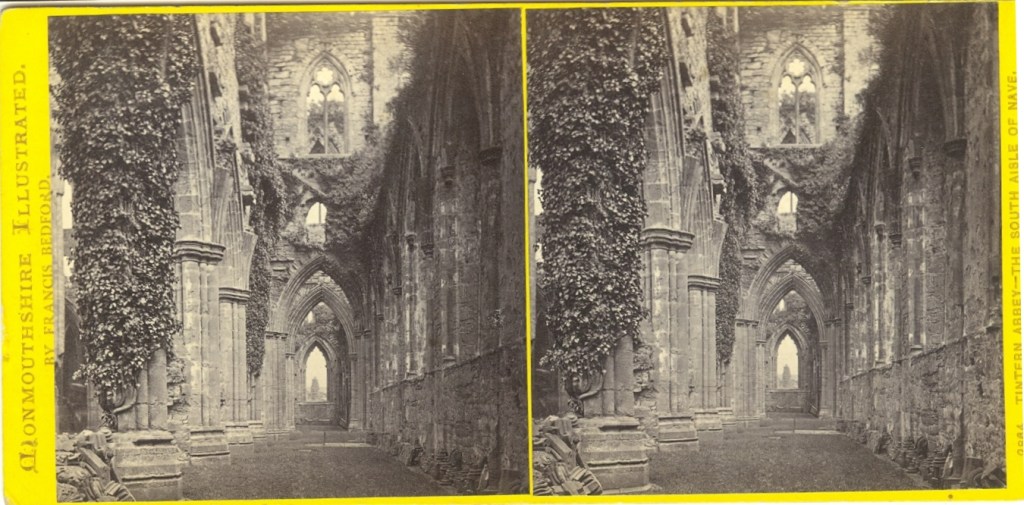

MONMOUTHSHIRE ILLUSTRATED SERIES

WARWICKSHIRE ILLUSTRATED SERIES

WORCESTERSHIRE VIEWS.

“Mr. Bedford’s last issue of stereographs is timely, consisting, as the views do, chiefly of scenes in Warwickshire, a county abounding at once in natural and in architectural beauties, and in hallowed and venerable associations. Perhaps no spot in England possesses, within the area of a few miles, so much to please the eye, and call up eventful memories. Stratford on-Avon, with its homely cottage in Henley Street, and noble Church, together with the neighbouring Shottery and Charlecote — the goal of many a pilgrimage; Warwick Castle, Guy’s Cliff’, and Kenilworth; Stoneleigh and its noble deer-park, and the Forest of Arden; and quaint old Coventry, with its three tall spires, its treasures of ancient and modern architecture, and its legends; pretty and fashionable Leamington, with its urban charms. The county abounds with scenes famous in English history, and Nature has been prodigal of those calm beauties which constitute the genuine English landscape. Mr. Bedford has produced nearly two hundred stereographs of the scenes of chief importance in the country. In such a number we might naturally expect to find varying degrees of excellence and interest, but by far the greater number are very perfect indeed, good alike in photography and in pictorial qualities.”

“Critical Notices.” PHOTOGRAPHIC NEWS 8:289 (Mar. 18, 1864): 136.

“Messrs. Catterall and Pritchard, of Chester, have sent us some photographs and stereoscopic slides, the productions of the eminent photographer, Bedford, which we have examined with exceeding pleasure. Those of size represent interiors in Hereford Cathedral; more especially views of the rood-screen and reredos, manufactured by Skidmore, of Coventry, which attracted so much attention at the International Exhibition in 1862. The smaller views are very varied: they represent the more attractive objects to be found at Hereford, Warwick, Cheltenham, Gloucester, Malvern, Coventry, Stratford-on-Avon, Kenilworth, and Chester. The points are in all cases well chosen. They thoroughly exhibit several of the most interesting “historic” cities and towns of England. In execution, the stereoscopic slides are clear, sharp, and of great excellence in all respects. The publishers have our thanks for the instruction and enjoyment they have thus afforded us.”

“Minor Topics of the Month.” ART-JOURNAL 27:6 (June 1,1865): 194.

THE HOLY LAND, EGYPT, CONSTANINOPLE, ATHENS, ETC., ETC.

[From the book Bedford, Francis. The Holy Land, Egypt, Constantinople, Athens, etc., etc. A series of forty-eight photographs taken by Francis Bedford for H. R. H. the Prince of Wales during the tour of the East, in which, by command, he accompanied his Royal Highness, with descriptive letterpress and interp. by W. M. Thomson. London: Day & Son, 1866. 2 vol. 48 I. of plates. 48 b & w.]

“Almost as numerous and as various as the scenes that the orb of day itself shines upon are the sun-pictures we see in our stationers’ windows and in every house we visit. How few of us who remember distinctly the first efforts of photography in taking the imprints of feathers, leaves, and bits of lace would have predicted from those childish essays, so great, so wonderful, so rapidly produced, an industry as photography has now become! Not that we are at all disposed to sing an unmitigated praise of photographers or their pictures, for with thorough artist’s feelings we see in their ordinary productions the defects of composition, the absence of that picture-painting of unspoken thoughts, and the want of many another quality that goes to make a perfect picture, while we as painfully perceive in many a way the deleterious effects of their productions on the prospects and qualities of painter-artists; but its good outbalances its evils, and photography flourishes and increases.” * * * * * “…In Mr. Bedford’s charming scenes in Egypt and the Holy Land, taken during the travels of the Prince of Wales, there is the same remarkable clearness and precision of architectural details, although his pictures are on a far smaller scale than those we have referred to, and this notwithstanding his great and successful efforts to pictorialize his views. In this latter respect his use of his optical instrument, his judicious choice of figures and selections of their positions, with the various delicate and unexposed manoeuvres to produce effects, and the tender manipulation of his pictures, render them merely works of art, and take Mr. Bedford out of the ranks of manipulators, and place him in that of true artists….” “From the “London Review.”

“Photography as an Industry.” PHOTOGRAPHIC NEWS 8:290 (Mar. 24, 1864): 153-154.

FRANCIS BEDFORD BIBLIOGRAPHY

By William S. Johnson.

(Please credit the blog if you use this bibliography.)

(POSTED May 2012, REVISED June, 2023)

[I have compiled and now posted this bibliography to test my belief that current technologies have made it possible to develop a very flexible research tool that can permit a scholar to access a wider range of information and provide a more nuanced look into the functioning of any particular era in the history of photography. This bibliography is composed from the Nineteenth-Century Photography. An Annotated Bibliography 1839-1879, by William S. Johnson. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1990, to which I’ve added a key-word search of my current bibliographic project of indexing more than 800 periodical titles published in the USA and England between 1835 and 1869. After 1869 additional references were drawn from other random projects or sources that I had on hand and a key-word literature search of the internet. Not every important source is on the internet and even though the size of this work (More than 800 pages.) surprised me; nevertheless, it should not be considered an exhaustive survey of the literature published after that date. WSJ]

COLLECTIONS

The Francis Bedford collection (purchased by the Birmingham (England) Public Libraries in 1985) consists of more than 2700 glass negatives and almost 2050 prints, and the manuscript catalogue of his negatives. In 2011 the Birmingham Library and Archive Services purchased an additional collection of 172 photographs from the ‘Tour in the East’ made in 1862 by the Prince of Wales, (the late Edward VII), which covered Athens, Corfu, Constantinople, Tripoli, Egypt, Syria and the Holy Land.

The Francis Bedford Archive was purchased by the National Gallery of Art Department of Image Collections in 2016. 4,397 photographs and two index volumes. [https://library.nga.gov/discovery/fulldisplay/alma991736003804896/01NGA_INST:IMAGE]

Bedford’s photographs are also held in the National Maritime Museum, London, the Royal Collection Trust, the Getty Museum, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, NY, the George Eastman House, Rochester, NY, and in many other art museums and galleries.

BOOKS

1841

Bedford, Francis. Sketches in York. York, England: H. Smith, 1841

14 unnumbered leaves of plates: color illustrations; 38 cm

[York Cathedral, from the north west —

View in water lane, York —

Walmgate Bar, York —

Bootham Bar, York —

Monk Bar —

Castle Yard, York —

York Cathedral, west front —

York Cathedral, the nave —

York Cathedral, the choir —

York Cathedral, from the south east —

St. Mary’s Abbey, York —

Ancient Norman porch, St. Margaret’s Church, York.”]

1843

Monkhouse, William and Francis Bedford. The Churches of York; by W. Monkhouse and F. Bedford, junr; with historical and architectural notes by the Rev. Joshua Fawcett. York: H. Smith, 1843. viii, 48 p. 26 plates. 38cm.

[Eight pages of introduction, followed by 26 historical essays, each one for an individual church. Each essay is preceded by a tipped-in lithograph (which, unusual for the period, are without any titles, or artists or publisher’s credits.]

Bedford, Francis. Sketches of York. York, England: H. Smith, 1843. n. p.

[From a library catalog. Possibly a duplicate of the above reference?]

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy. MDCCCXLIII. The Seventy-Fifth. London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, Printers to the Royal Academy. 1843.

[“Architecture.”

1271 Interior-York Cathedral, from the transept F. Bedford [May be the Father.] (Etc., etc.) (p. 48)]

1844

Bedford, Francis. A Chart of Anglican Church Architecture: Arranged chronologically with examples of the different styles. “5th ed.” York: R. Sunter, 1844. 1 folded sheet (15 pages): chiefly illustrations; 55 x 38 cm, folded to 12 cm.

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy. MDCCCXLIV. The Seventy-Sixth. London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, Printers to the Royal Academy. 1844.

[“Architecture.

1140 Choir of St. Saviour’s Church, Southwark; the stained glass and the statues in the altar screen restored F. Bedford. [May be the Father.]”]

1845

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy. MDCCCXLV. The Seventy-Seventh. London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, Printers to the Royal Academy. 1845.

[“Architecture.

1172 Summer morning—banks of the Rhine G. Franklin

1173 Fishing boats landing, Hastings, Sussex W. R. Earl

1174 Distant view of London J. B. Hill

1175 Ruins of the Chapter House, Furness Abbey, Lancashire W. B. S. Taylor

1176 Hotel de Ville, Louvaine G. S. Clarke

1177 St. Augustine’s gateway, Canterbury F. Bedford, jun.

1178 The north-east view of a design for the Episcopal chapel, at the Nunhead Cemetery; which was submitted in competition, and obtained the second premium . W. H. Brakspear

1179 South-west view of the new church of St. Helen, in course, of erection at Thorney, in Nottinghamshire, for the Rev. Christopher Neville, M.A., from the designs, and under the superintendence, of L. N. Cottingham and Son (Etc., etc.) (p. 45)]

Bedford, Francis. The Architecture of York Cathedral, Arranged chronologically. York: W. Hargrove, Oxford: J. W. Parker, London: Hamilton Adams & Co., 1845. n. p., folded pp. illus.

Whichcord, John. The History and Antiquities of the Collegiate Church of All Saints, Maidstone, With the Illustrations of Its Architecture; Together with Observations on the Polychromatic Decoration of the Middle Ages. By John Whichcord, Jun., Architect. Thirteen Engravings, Some of Which are Illuminated Fac-Similes. London: John Weale. 1845. 1 p. l., 25, 15 p.13 pl. (part col.) 31 cm. [Francis Bedford generated all of the colored lithographic plates, i.e. 8, 10, 11, 12, 13. WSJ]

[Plate I. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. General Plan.” .” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”

Plate II. “All Saints Church, Maidstone.” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”

Plate III. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Elevation of part of North Aisle of Chancel.”.” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”.

Plate IV. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Plans and elevations.” ”J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”.

Plate V. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Elevation.” “J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”.

Plate V. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Plan of.” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”

Plate VI. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Plan of Sedelia and Tomb.” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”

Plate VII. “All Saints Church, Maidstone.” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “John LeKeux sc”

Plate VIII. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Figs. 1. to 9. Bosses. Fig. 10. Strawberry Leaf Enrichment Surmounting Cornice of Tomb.” J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “F. Bedford;, Litho London.”

Plate IX. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. [Floor plans and windows.] J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “W. A. Beever, sc”

Plate X. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Elevation of Oak Screen, in Chancel.” “J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “F. Bedford;, Litho London.”

Plate XI. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Elevation of Tomb, at back of Sedilia.” “J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “F. Bedford;, Litho London.”

Plate XII. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Painting on Back of Recess. Wotton’s Tomb.” “J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “F. Bedford;, Litho London.”

Plate XIII. “All Saints Church, Maidstone. Painting on East Wall of Recess. Wotton’s Tomb.” “J. Whichcord, Jun., Archt, Del.” “F. Bedford;, Litho London.”

1846

Bedford, Francis. A Chart of Anglican Church Ornament, wherein are figured the Saints of the English Calendar, with their appropriate Emblems, the different Styles of Stained Glass, &c., by F. Bedford;, in a sheet, 3s. 6d. 1846.

The same, mounted in case, 4s. 6d. [“…No. 506 A Chart Of Anglican Church Ornament; Wherein are figured the Saints of the English Kalendar, with their appropriate Emblems; the different Styles of Stained Glass; and various Sacred Symbols and Ornaments used in Churches. By Francis Bedford, Jun. Author of a “Chronological Chart of Anglican Church Architecture, “&c.”

Johan Weale’s 1845 Catalog Supplement. and

Johan Weale Catalogue of Books on Architecture, etc. 1854…}

Bedford, Francis. Examples of ancient doorways and windows, arranged to illustrate the different styles of church architecture from the Conquest to the Reformation, from existing examples, by F. Bedford, Junr. London: John Weale, [1846]. 1 folded sheet: ill.; 43 x 32 cm., folded to 15 x 12 cm.

Sheet divided into 9 sections and mounted on cloth. Bound in red book cloth, stamped in blind and gilt.

[…“No. 507. “By the same Author, uniform with the above, Price 3s. Examples of Ancient Doorways and Windows; Arranged to illustrate the different Styles of Gothic Architecture, from the Conquest to the Reformation. It has been the aim of the Author of this little Chart to present such examples as may most clearly illustrate the successive changes in style, together with a few remarks on the characteristic peculiarities which marked each period. The names of the Buildings from which the examples are selected, are in all cases given.” John Weale’s 1845 Catalog Supplement. (p. 4)]

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy. MDCCCXLVI. The Seventy-Eighth. London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, 14, Charing Cross., 1846.

[“Architecture.”

1299 View of Westminster Abbey, looking west. F. Bedford, jun. (p. 52)

“List of the Exhibitors, 1846, with their places of Abode.”

Belford, F., Jr. 18, Hampton-place, Gray’s-inn-road.1299. (p. 61)]

Bedford, Francis. A Chart Illustrating the Architecture of Westminster Abbey. London: W. W. Robinson. [1846]. 1 sheet: chiefly ill.; 56 x 44 cm., folded to 20 x 15 cm. Linen back folded chart which opens into 9 sections depicting the architecture of Westminster Abbey. Views and details of Westminster Abbey on tinted bisque background with gothic frame, black letter with red initials. The illustrations are drawn and lithographed by F. Bedford, Jun. and printed by Day & Haghe.

[“It would be difficult to select from among all the beautiful piles, which the zeal and taste of our ancestors have left us, a monument in which the several varieties of Pointed Architecture are more perfectly illustrated than in the Abbey Church of St. Peter, at Westminster. The exquisite and airy grace of the lofty pointed Arch and clustered Shafts of the Early English Style, the beautiful purity of design and enrichment of the Decorated, and the elaborate profusion of ornamental detail which marked the Perpendicular or Tudor work, each and all find here most glorious representatives. To describe the peculiarities which characterised the successive changes in English Architecture is not the object of this Chart; but it may not be amiss to point out briefly, in connection with the examples selected from different portions of the Abbey, those distinctive features of style which they illustrate.) The style which began to prevail at the close of the Twelfth, and continued during the greater part of the Thirteenth, Century, and which is usually known by the name of Early English, is exemplified in the Views of the North Transept, the South Aisle of the Nave, and in the Elevation of one compartment of the interior of the Nave….” (Etc., etc.) [One page introduction by Francis Bedford on inside front cover.]

Hackle, Palmer. Hints on angling, with suggestions for angling excursions in France and Belgium, to which are appended some brief notices of the English, Scottish, and Irish waters. By Palmer Hackle, Esq. London: W. W. Robinson, 1846. xvi, 339 p. [Advertisement] “Architecture of Westminster Abbey.”

Just Published,

To fold in an Ornamental Cover, Price 7s. 6d., or on a Sheet, 5s.

A Chart Illustrating the Architecture of Westminster Abbey. Drawn and Lithographed by F. Bedford, Jun. This Chart exhibits the different styles-Early English, Decorated, and Perpendicular-the combination of which makes the Abbey

Church of St. Peter, Westminster, a chef d’œuvre of Ecclesiastical Architecture. It contains views of the Exterior and Interior of the Abbey; Tombs, Shields, Statues, Panels, and Ancient Paintings.

W. W. Robinson, 69, Fleet Street.” (p. 340)]

Lamb, Edward Buckton, architect. Studies of Ancient Domestic Architecture, Principally Selected from Original Drawings in the Collection of the Late Sir William Burrell, Bart., With Some Brief Observations on the Application of Ancient Architecture to the Pictorial Composition of Modern Edifices. London: John Weale.1846. viii, 30 pages, 20 leaves of plates: illustrations (lithographs);38 cm

[List of Plates.

I. “Passingworth, in Waldon” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

II. “Chequers Court, Bucks. Restored” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

III. “Ote Hall, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

IV. “Tanners, in Waldon, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

V. “West Front of Riverhall, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

VI. “At Harrold, Bedfordshire.” “E.B. Lamb, Archt Del.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

VII. “At Yaverland, Isle of Wight.” “E.B. Lamb, Archt Del.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

VIII. “West Front of Plumpton Place, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

IX. “Packshill, Sussex. “ “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

X. “Ewehurst, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XI. “Drenswick Place, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XII. “Hammond’s Place, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XIII. “North-east View of Brandeston Hall, Suffolk.” “E.B. Lamb, Archt Del.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XIV. “East View of Derm Place, Horsham, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XV. “Mr. Clutton’s, Cuckfield, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XVI. “Seddlescomb or Selcomb Place, Sussex.” “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XVII.” At Lincoln.” “E.B. Lamb, Archt Del.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XVIII. “Cookham Tower, Sussex”. “E.B.L. del. From Drawing by S. H. Grimm.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XIX. “At Lincoln.” “E.B. Lamb, Archt Del.” “F Bedford, Litho.”

XX. “West Gate, Peterborough.” “E.B. Lamb, Archt Del.” “F Bedford, Litho.”]

Suckling, Alfred Inigo. The History and Antiquities of the County of Suffolk: With Genealogical and Architectural Notices of Its Several Towns and Villages. By The Rev. Alfred Suckling, Ll. B. Rural Dean, Rector of Barsham, &c. Vol. I. London: John Weale, 59, High Holborn. 1846-48. 2 v. col. front. (v. 2) illus. (incl. coats of arms) plates (part col.) port., plans, fold. geneal. tab. 30 x 23 cm.

Vol. 1: 66 illustrations total, 17 lithographic plates tipped-in (16 credited to F. Bedford). The other engravings printed with the text.

[“ List of Illustrations. (Edited to show Bedford only).

- “South Porch, Beccles Church.” “A. T. Suckling Del. March, 1845” “ “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 15

- “Beccles Church &c, from the N. E.” “A. T. Suckling Del. Febr, 1845” “ “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 17.

- “Sir John Suckling, the Poet.” “Vandyke, pinxt.” “Jas Thomson, sculpt.” to face p. 39

- “East End of Barshan Church.” “A. T. Suckling Del. Febr, 1845” “ “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 41.

- “Brass at Barsham Church.” “F. Bedford Litho.” London.” to face p. 43

- “Brass Effigies of Nicholas Garneys and Family” (Not credited) to face p. 69.

- “The Old Hall, Shaddingfield.” “Drawn by the Rev. G. Barlow” “F. Bedford, Litho.” to face p. 73.

- “Stained Glass, Sotterly Church.” “A. T. Suckling Del. Febr, 1845” “ “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 83.

26.* “Brass Effigies (1, 2, 3) In Sotterley Church.” (Not Credited) to face p. 89 - “St. Mary’s Church, Bungay” “A. T. Suckling Del. Febr, 1845” “ “F. Bedford Litho.” to face p. 149.

- “Gateway of Mettingham Castle” “A. T. Suckling Del. Febr, 1845” “F. Bedford Litho,” to face p. 173.

- “Flixton Hall, Suffolk” “R. B. Coe, delt.” “F. Bedford Litho.” London.” to face p. 200.

- “The Galilee, Mutford Church.” “A. T. Suckling Del. “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 275.

- “View of Pakefield.” “Drawn by Mrs. Cunningham.”. “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 281.

- “Brass Effigy of Richard Folcard.” “Alfred Suckling del. “F. Bedford Litho, London.” to face p. 285

- “Compartment of Screen in Blundeston Church.” “Miss Dowson, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho”” to face p. 318

- “Fritton Church and Ground Plan “ “A. Suckling Del.” “F. Bedford Litho”” to face p. 353-

- “Brass Effigy in Corleston Church.” “F. Bedford, Litho. London” “Printed by Standidge & Co.” to face p. 373.”]

—————————————

Vol. 2: 77 illustrations total, 17 lithographic plates tipped-in (credited to F. Bedford). The other engravings printed with the text.

[ List of Illustrations. - “Screen, Bramfield Church,” “Drawn by Alfred Suckling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face title-page.

- Interior of the Crypts in St. Olave’s Priory. “Alfred Suckling, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 19.

- “Oulton High House, Ancient Mantel-Piece.” “Drawn by Miss J. Worship.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 37

- “Brass in Oulton Church.” “F. Bedford Litho. London.” “Printed by Standidge & Co.” to face p. 39

- “Somerleyton Hall.” “Drawn by Alfred Suckling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 47

- “Lowestoft Church from the S. E.” “Drawn by Mrs. Cunningham.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 99

- “Blythborough Church. Interior.” “Drawn by Alfred Suckling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 151

- “Blythborough Church from the S. E.” “Drawn by Alfred Suckling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 151

- “Poppy-Heads, Blythborough Church.” “Drawn by H. Watling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p.155

- “Bramfield Church from the S. E.” “Drawn by Alfred Suckling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 175

- “Bramfield Church. Monument of Arthur Coke, Esq.” “Drawn by Alfred Suckling.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 176

- Font in Cratfield Church.” “Drawn by Miss Jane Worship.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face 215

- “Ruins of the Convent of Franciscan Friars. Dunwich.” “Drawn by Mrs. Barne.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 283

- “Dunwich Seals.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 292

- “Ancient Mantel-Piece. From an Old House, Halesworth.” “H. Watling, Del.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 336

- “West Doorway, Halesworth Church.” “Drawn by Miss Jane Worship.” “F. Bedford, Litho., London” to face p. 341

- Interior of the Great Court, Henham, Old Hall.” “F. Bedford, Litho. From an Old Drawing in the possession of the Earl of Stradbroke.”” to face p. 355.”]

1848

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy. MDCCCXLVIII. The Eightieth. London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, 14, Charing Cross, 1848.

[“Architecture.”

1170 Magdalen Tower, from the bridge, Oxford F. Bedford. (p. 47)

“List of the Exhibitors, 1848, with their places of Abode.”

Belford, F., 18, Hampton-place, Gray’s-inn-road.1170. (p. 59]

1849

The Exhibition of the Royal Academy. MDCCCXLVIX. The Eighty-First. London: Printed by W. Clowes and Sons, 14, Charing Cross, 1849.

“Architecture.”

1109 West Front of York Minster F. Bedford. (p. 47)

“List of the Exhibitors, 1849, with their places of Abode.”

Belford, F., 18, Hampton-place, Gray’s-inn-road.1109. (p. 56)]

1850

Poole, George Ayliffe. An Historical & Descriptive Guide to York Cathedral and Its Antiquities. By Geo. Ayliffe Poole, M.A., Vicar of Welford, and J. W. Hugall, Esq., Architect. With a History and Description of the Minster Organ. York: Published by P. Sunter, Stonegate. [1850] xiii, 213 pages, 43 unnumbered leaves of plates; illustrations (some color); 30 cm.

[“Title page.”

“To the very reverend William Cockburn D. D. Dean of the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter of York and to the Residentiaries and Canons of the same Church this Little Work is inscribed with feelings of respect and esteem by their most obedient humble servant the Publishers.” (Lithographic dedication page, facing p. iii.)

“Preface.” (p. iii)

“A Series of Views Plates of Detail and Antiquities from the Cathedral Church of Saint Peter of York. Drawn on stone by F.

Bedford. York. Robert Sunter. MDCCCL” (Lithographic title page, following p. viii.)

“Ground Plan of the Cathedral Church of St. Peter, York.” “From a Plan in Britton’s York Cathedral.” “F. Bedford, Litho.

“ Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (folded print preceding p. ix.)

[Text pages. pp. ix-x]

“St. Peters Cathedral, York. Published by R. Sunter, York. Hamilton and Adams, London” “F. Bedford, Litho. Day & Son

litho to the Queen.” (Second lithographed title page, facing p. x.)

[Text pages. pp. xi. – xiii.]

“York Cathedral. S. E. View.” ““F. Bedford, Del & Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (following p. xiii.)

“York Cathedral. N. W. View.” ““F. Bedford, Del & Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (following p. xiii.)

[Text pages. pp. 1-213]

“Plate II. York Cathedral. Pillars from the Crypt.” “J. Sutcliffe del., F. Bedford Litho.” (facing p. 24)

“Plate III. York Cathedral. Capitals from the Crypt.” “J. Sutcliffe del., F. Bedford Litho.” (facing p. 26)

“York Cathedral. South Transcript.” F. Bedford, Del & Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 46)

“York Cathedral. North Transcript.” F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 48)

“York Cathedral. North Transcript. (Interior) ” F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 49)

“York Cathedral. South Transcript. (Interior) ” F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 50)

“York Cathedral. Large Bracket, Finials and Poppy Head.” ” F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Haghe litho to the Queen.” (facing

page 51)

“York Cathedral.Gargoyles, Pendents, Bosses and Head.” ”F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Haghe litho to the Queen.”

“York Cathedral. West Front.” “F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 66)

“Plate IX. York Cathedral. Specimens of Stained Glass from the West Window.” “F. Bedford, Litho.” (facing page 68)

“York Cathedral. The Nave, looking East.” (Interior) “F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 75)

“York Cathedral. Heads, Capitol & Sculptured Panel.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Haghe litho to the Queen.” (facing page

78)

“Plate XIII. York Cathedral. Specimens of Stained Glass from the East Window.” “F. Bedford, Litho” . “Day & Haghe litho

to the Queen.” (facing page 98)

“York Cathedral. East End.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 102)

“York Cathedral. The Choir.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 108)

“York Cathedral. The Creen.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (folded print preceding page 119)

“York Cathedral. Shields from the Central Tower” “T. Sutcliffe del. F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.”

(following page 126)

“York Cathedral. Shields from the Central Tower. East Side.” “T. Sutcliffe del. F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the

Queen.” (following page 126)

“York Cathedral. Shields from the Central Tower. West Side.” “T. Sutcliffe del. F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the

Queen.” (following page 126)

“York Cathedral. Tomb of Ancestors for Walter Grey.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page 160)

“York Cathedral. Monumental Brass Arch.BP of Greenfield” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (facing page

162)

“York Cathedral. Tomb of John Haxley.” “A. H. Cater, del. “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 164)

“York Cathedral. Sepulchral Crosses.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Haghe litho to the Queen” (facing page 182)

“York Cathedral. St. Peter’s Well.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Haghe litho to the Queen” (facing page 187)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Pastorial Staff.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 190)

“York Cathedral. Horn of Ulphus.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 191)

“York Cathedral. Plan of Saxon and Norman Remains. .” “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 192)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Silver Chalices with Cover.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 194)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Silver Chalices with Cover.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (following page 194)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Spere Head, Helmet, Spur & Rings.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (following page 194)

“York Cathedral. ArchBP Scrope’s Mazer Bowl.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 196)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Coronation Chair.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (facing page 198)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Encaustic Tiles.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (following page 198)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Sculpture. Virgin & Child.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (following page 198)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Sculpture. Virgin & Child.” “F. Bedford, Litho” “Day & Son litho to the Queen.” (following page 200)

“York Cathedral. Ancient Chest.” “A. H. Cates, del.” “F. Bedford, Litho” (folded page following page 200)

“Description of the Plates.”

“The title-page is designed from the door leading into the vestibule of the Chapter-house from the North transept, with the addition of several heraldic insignia, connected with the ecclesiastical history of York. The first at the top is the ancient coat of the see, and the other is the arms of the city of York. Below these is the archiepiscopal mitre, as it is now borne with the ducal cincture, an appendage not found in the ancient mitres of Archbishops, as may be seen in the brass of Archbishop Greenfield, figured in Plate XX. The four lower coats are those of the Chapter of York, and of Bishop Skirlaw, at the top, and of St. Wilfrid, and of King Edwin, at the bottom. These four occupy the sides of the great Lantern-tower, in the interior: the two last (p. 192) are of course only conventionally appropriated to the persons whose names they bear. Plate I. — Ground plan of the Saxon and Norman remains in the crypt. A Saxon choir, probably part of the stone church of Paulinus. B Norman church of Archbishop Thomas. C Norman church of Archbishop Roger. D Chamber of access to crypt from the church. E Ambulatory to crypt. F G-H Aisle, body and transept of crypt. K Crypt of present choir. M Base of walls of present choir. a a Enriched Norman door to crypt. b Place over which the High Altar stood, and proba- bly the centre of the chord of the Eastern apse, both of the Saxon and of the Norman choir. c Floor of Saxon choir. d Steps to Saxon crypt. e Place of Norman staircase in the tower above, supported by arch . g Commencement of apsidal chapel in the North transept of the church of Archbishop Thomas….” (Etc., etc.) (p. 193)]

1851

Official Catalogue of the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry of all Nations, 1851. London, Spicer brothers [1851] 320 p. 22 x 18 cm.

“The present volume is a very condensed abstract of [the Official descriptive and illustrated catalogue] … having been prepared by Mr. G. W. Yapp.”–Introd., signed: Robert Ellis.

At head of title: By authority of the Royal commission.

[“UNITED KINGDOM.

CLASS 30. Sculpture, Models, and Plastic Art, Mosaics, Enamels, &c.

SECTION IV.-FINE ARTS.

TRANSEPT.

BAILY, E. H. 17 Newman St. Sculp.-A Youth sitting after the Chase. A Nymph preparing for the Bath.

BRUCCIANI, D. 5 Little Russell St. Manu-Plaster bust of Apollo Belvedere, from the original, to imitate marble,

BURNARD, N. 36 High St. Eccleston Sq. Des. and Sculp.-The Prince of Peace, Isaiah. ix. 6.

DAVIES, E. 67 Russell Pl. Fitzroy Sq. Sculp.- Venus and Cupid…. * * * * * (p. 145)

UNITED KINGDOM.

CLASS 30. Sculpture, Models, and Plastic Art, Mosaics, Enamels, &c.

BOND, C. Edinburgh, and 53 Parliament St. London. -Model of Highland cottage, combining simplicity of construction, comfort, warmth, ventilation, and economy.

BONE, H. P. 22 Percy St. Prod.-Enamel paintings.

BREMNER, J. James Ct. Edinburgh, Des. and Chaser. -Specimens of silver embossed chasing in heraldic and other styles of ornament, intended chiefly to be used for brooches.

COWELL, S. H. Ipswich, Suffolk.-Specimens of anastatic printing, as applied to original drawings in chalk or ink, ancient deeds, wood engravings, archæological illustrations, &c.

DAY, R. 1 Rockingham Pl. New Kent Rd. Mod Portico of the Parthenon at Athens; Temple Church, Fleet St.; portico of the Pantheon at Rome; the Martyrs’ Memorial at Oxford; a chancel in decorated Gothic, the window from Herne Church, Kent.

DAY & SON, 17 Gate St. Lincoln’s Inn Flds.- Specimens of tinted and chromo-lithography, by and after Haghe, G. Hawkins, E. Walker, M. Digby Wyatt, and F. Bedford.

DAYMOND, J. 5 Regent Pl. Westmer. Des. and Sculp.-Vase and flowers, in marble. …” (Etc., etc.) (p. 147)]

Wyatt, Matthew Digby, Sir. The Industrial Arts of the Nineteenth Century. A series of illustrations of the choicest specimens produced by every nation at the Great Exhibition of the Works of Industry, by Matthew Digby Wyatt. London: Day and Son, 1851-1853. 2 vol. 158 chromolithographs. Illustrated by Francis Bedford, John Clayton, Edward Dalziel, Philip Henry Delamotte, Henry Noel Humphreys, Henry Clarke Pidgeon, W.W. Pozzi, H. Rafter, John Sliegh, Frederick Smallfield, Alfred Stevens and John Alfred A. Vinter. 158 of the colored lithographic illustrations for this work were created by Bedford.]

1852

Carpentry; Being a Comprehensive Guide Book for Carpentry and Joinery; With Elementary Rules for the Drawing of Architecture in Perspective and by Geometrical Rule: Also, Treating of Roofs, Trussed Girders, Floors, Domes, Stair-Cases and Hand-Rails, Shop-Fronts, Verandahs, Window-Frames, Shutters, &c. &c.; and Public and Domestic Buildings, Plans, Elevations, Sections, &.c &c. Vol. II. One Hundred and Sixteen Engravings. (Being The Practical Part for the Use of Carpenters and Joiners.) London: John Weale, 59 High Holborn. 1852. 2v. illus, plates. 28 cm.

[ Plates

Illustrations of Shop Fronts, Elevation, Plan, and Details:-

Ladies’ Shoe Maker’s, Mount Street, Grosvenor Square.. 2 plates

Dyer’s, Elizabeth Street, Chester Square. . . 2 plates

Umbrella and Cane Shop, Regent Street.. 2 plates.

Tailor and Draper’s, Regent Street .. 2 plates

Elizabethan Terminations of Shop Fronts and Consols 1 plate

[There are four color lithographs (of the shop fronts) and five b & w prints of plans and details. The digital copy is underexposed, making many of the credit lines under the prints illegible; but “F. Bedford, Litho, London” is visible under the color prints.]

Masfen, John. Views of the Church of St. Mary at Stafford. By the Late John Masfen, Jun. With an Account of its Restoration, and Materials for Its History. London: John Henry Parker, 377, Strand. 1852. 42 p. 16 leaves of plates, 39 cm.

[ “Printed by Day and Son, Lithographers to The Queen, 17, Gate Street, Lincoln’s-Inn-Fields, London.” (Verso of the title page.) Day and Son was the publisher of Bedford’s lithographs at this time. The digital copy of this book is underexposed, so that most of the attributions under the prints are illegible. But several, including the full-color frontispiece, are credited “F. Bedford Lith.” and I feel that most, if not all of the other prints were made by him. WSJ]

Wyatt, M. Digby, Architect. Metal Work and Its Artistic Design. London: Printed in Colours and Published by Day & Son, Lithographers to the Queen, 17, Gate Street, Lincoln’s Inn Fields. MDCCCCLII. [1852} lii, 81 pages, L leaves of plates: illustrations (some color); 49 cm

Added title page illustrated in colors, included in number of plates.The plates are credited as drawn by various artists, but all lithographed by F. Bedford and Printed by Day and Son, Lithographers to the Queen.

[ List of the Plates.

I. The Frontispiece: being a Design for a precious Book-cover, introducing many of the most elaborate processes of Metal Working.

II. Iron Screen, from the Church of Santa Croce, Florence.

III. Bronze Candelabrum, in the possession of Lewis Wyatt, Esq..

IV, Italian Enameled Chalices and Ciboria.

V. Iron Grilles from Venice, Verona, Florence, and Sienna.

VI. English and German Door-handles, and Lock-escutcheons.

VII. Venetian and Bolognese Knockers, in Bronze.

VIII. Reliquaries and Thurible, from near Düsseldorf.

IX. Hinges from Frankfort-on -Maine and Leighton Buzzard.

X. Locks and Keys, from the Hotel de Cluny, Paris, and in private possession.

XL Bronze Figures, from the Gates of the Baptistery at Florence.

XII. Chalice, brought from La Marca, in the possession of the Marquis of Douglas.

XIII. Hinges, — English, French, and Flemish.

XIV. Burettes and Thuribles, from the Louvre and Hotel de Cluny, Paris.

XV. Bronze Door-handle, from the Rath-haus, at Lubeck.

XVI. Processional Cross, from the Museum of Economic Geology, London.

XVII. German and Italian Bracket-lamps.

XVIII. Bronze Figures, from the Font at Sienna and Shrine of San Zenobio, at Florence.

XIX. English and German Locks and Keys.

XX. Pastoral Staff of San Carboni, preserved in the Cathedral at Sienna,

XXI. Italian Chalice and Ciborium, with German Monstrances.

XXII. Pendant Lamps, from Venice, Rome, Perugia, and Nuremberg.

XXIIL German and Flemish Hinges and Door-latches.

XXIV. Double Reliquary, from the Treasury of St. Mark’s at Venice.

XXV. A Group of Enamelled Objects exhibited at the Salisbury Meeting of the Archaeological Institute of Great

Britain and Ireland, held in 1849.

XXVI. Bronze Ornaments, from the Gates of the Baptistery, Florence, and from a Candelabrum (l’Albero)

Cathedral.

XXVII. Pendant and Processional Lamps, from the Cathedral of Lubeck.

XXVIII. Silver-gilt Reliquary, from the Cathedral of Pistoia,

XXIX. Details of Door-Furniture from St. George’s Chapel, Windsor.

XXX. Chalice and Paten, from Randazzo, in Sicily.

XXXI. English and German Door-handles.

XXXII. A Group of Chalices and Patens, from Randazzo, in Sicily.

XXXIII. Wrought-Iron Grilles, from Rome and Venice.

XXXIV. Hinges, and Details of Iron-work, from Oxford.

XXXV. Lectern in Brass, from the Cathedral at Messina.

XXXVI. A Group of Flemish Drinking-Cups; Wiederkoms and .

XXXVII. Lock-plate and Key, formerly belonging to an old house at Wilton, in Wiltshire.

XXXVIII. Portions of the Screen surrounding Edward IV.’s Tomb, in St. George’s Chapei, Windsor.

XXXIX. Specimens of Jewellery, executed by Froment Meurice, of Paris.

XL. Chalice, brought from La Marca, in the possession of the Marquis of Douglas.

XLI. Wrought-Iroii Gates of the Clarendon Printing-Olfice, Oxford.

XLII. Sicilian Clialice and Venetian Drinking-Cup.

XLIII. Locks, from Nuremberg.

XLIV. Italian Reliquaries, Pix and Crystal Vase, mounted in gold.

XLV. Italian Silver Dagger, and Coins by Cellini; and Bronze Ornament, from the Church of La Madeleine,

Paris.

XLVI. Chalice, from the Treasury of the Cathedra! at Pistoia.

XLVII. Filagree Enamel Brooch, German Jewellery, and Enamels from the Altar Frontal of San Giacomo, Pistoia.

XLVIII. Italian, German, and Flemish Door-handles, Finials, and Crockets, all in Wrought-iron.

XLIX. A Group of Objects, the principal being the Enamelled Chalice and Patea, from Mayence Cathedral.

L. Wrought-Iron Doors, from the Cathedrals of Rouen and Ely.” ]

1855

Bedford, Francis. Examples of Ornament. Selected chiefly from Works of Art in the British Museum, Museum of Economic Geology, the Museum of Ornamental Art in Marlborough House, and the new Crystal Palace. Drawn from Original Sources, by Francis Bedford… and edited by Joseph Cundall. London: Bell & Daldy, 1855. 5, [2] p. 24 I. of plates, illus. 34cm. [“Consisting of a Series of 220 Illustrations (69 of which are richly coloured), classified according to Styles, and chronologically arranged: commencing with the Egyptian and Assyrian, and continued… These Illustrations have been selected by Joseph Cundall from existing specimens, and drawn by Francis Bedford, Thomas Scott, Thomas MacQuaid, and Henry O’Neill.”]

Photographic Club. Photographic Album for the year 1855. (1855)

Frontispiece, a portrait of Sir John Herschell,

Gorge of Gondo, Switzerland, by Sir Joscelyn Coghill;

View of the Grinddwald, by W. C. Plunket;

L’ Auberge de L’Etoile, Val d’ Enfer, Grand Duchy of Baden, J. J. Heilmann.

Highland Cottage, near Loch Fine, Argyleshire, by T. L. Mansell.

A View on the River Blackwater, by F. S. Currey,

Camp at Sebastopol, by Roger Fenton,

River Douro, by Mr. J. J. Forrester

Salisbury Cathedral, by R. W. S. Lutwidge

Hurstmonceaux Castle, Sussex,

Eashing village, near Godalming, by the Hon. Arthur Kerr,

A Pool in Warwickshire, by Dr. Percy

Bredicot Court, Worcestetshire, by B. B. Turner,

Castle of the Desmonds, by Lord Otho Fitz Gerald,

The Wool Bridge, Dorsetshire, by T. H. Hennah,

Green Meadows, by G. Shadbolt

Piscator, by J. D. Llewellyn

Fishing Smack in Tenby Harbour, by G. Stokes,

The Hippopotamus at the Zoo, by the Count de Moritzon. [sic Montizon]

Youth and Age, by Fallon Horne

Fortune Telling, by Rejlander

Innocence, by P. H. Delamotte,

A Study of Plants, by Francis Bedford

Interior, an Old Elizabethan Mansion, by Lieutenant Petty

[This information is from a secondary source (an article published thirty years later by J. Vincent Elsden, in the British Journal of Photography for Sept. 25, 1885) and it may be incomplete or inaccurate. However this citation verifies the information somewhat. The project only lasted for two or three years. WSJ

“Town and Table Talk on Literature, Art, &c.” Illustrated London News 28:797 (Sat., May 3, 1856): 475. [“…The biographers describe in very enthusiastic language the beauties of a folio volume of fifty photographs by fifty different hands, and those of eminence, to which Mr. Whittingham, of Chiswick, has attached fifty pages of letterpress of corresponding beauty. The volume is a present to her Majesty, and is one of fifty-two copies of a series of photographs made by members of the Photographic Club—a newly-established club akin to the old Etching Club, and instituted to advance and record the progress of the art of photography. This is their first volume, and most wonderfully does it exhibit the progress which photography has made in England during the past year. Each of the fifty members sends fifty-two impressions of what he considers to be his best photograph with a description of the process used in obtaining it. Fifty copies are distributed among the fifty; the fifty-first is offered to her Majesty, and the fifty-second presented to the British Museum. Very wonderful, indeed, are some of the photographs in this very beautiful volume. We would especially point out as perfect in their truth to nature and adherence to art Mr. Batson’s “Babblecombe bay,” Mr. Henry Taylor’s “Lane Scene,” Mr. Llewellyn’s “Angler,” Mr. Bedford’s “Flowers,” Mr. Delamotte’s “Innocence,” Dr. Diamond’s “Interior of Holyrood,” Mr. Henry Pollock’s “Winsor Castle,” Mr. Mackinlay’s “Bediham Castle,” Mr. White’s “Garden Chair,” and Mr. John Stewart’s appropriate vignette to the volume—the portrait of Sir John Herschel.”]

Further:

“‘A Copy of the Photographic Album’ (Fading Photographs).” Photographic Journal 7:114 (Oct. 15, 1861): 285-286. [“To the Editor of the Photographic Journal. October 5, 1861. Sir,-As the last volume of the ‘Photographic Album’ is now before me, which has been carefully wrapped up since its delivery and preserved in a dry place, I fear the following notes on the pictures therein will not be thought very satisfactory for the permanence of photographic works in general. We must remember that all the pictures were produced after the report of “Mr. Pollock’s Fading Commitee,” and several of them are by members of that Committee. No doubt, on the occasion of the production of a volume like this, all care was taken by the several contributors that their works should appear to the best advantage; and should you think it worthy of a place in the Journal, the present notice will draw their attention to the subject, and probably some will be enabled to compare their practice then with their present mode of manipulation, and good results may thereby ensue.

A Member of the Photographic Club.

The Photographic Album. Vol. ii. (Thirty nine Pictures.)

Quis solem dicere falsum and eat?—-Virg.

The Frontispiece —- Durham’s beautiful Bust of Her Majesty the Queen. By Dr. Diamond.

A truly effective photograph; but the white parts are all becoming yellow, premonitory of future decay.

- Jerusalem: Site of the Temple on Mount Moriah. By John Anthony, M.D.

Faded very much; all the delicate shadows gone; what was a very excellent picture is now a miserable production. - Wild Flowers. By Mark Anthony.

Remains as perfect as when produced. - Babbicombe from the Beach. By Alfred Batson.

Yellow, and fast decaying. - Pont-y-pair, North Wales. By Francis Bedford.

A very beautiful picture, as perfect as the day it was printed. - The Lesson. By W. G. Campbell.

An admirable picture, with great artistic excellence; remains quite perfect. - The Castle of Chillon. By Sir Joscellyn Coghill, Bart.

The sky and water have become of one dirty-yellow tint. The mountains in the distance, which were well given and very effective, are now scarcely visible; the picture will soon disappear. - Winter. By C. Conway. Quite fresh and beautiful.

- Highlanders. By Joseph Cundall.

Almost obliterated, the foot of one of the worthies having vanished into the floor. - The Court of Lions, in the Alhambra, Spain. By John G. Grace.

Remains in a very satisfactory state; the tone is admirable. - Wood Scene, Cheshire. By Thomas Davis.

Full of breadth, and no signs of change. - Art Treasures’ Exhibition. By P. H. Delamotte.

Beautifully soft and effective; quite unchanged. - Bury St. Edmunds. By George Downes.

Almost vanished; the tomb-stones in front of the Abbey are all blended together, and the print has a yellow tint all over. - Birth of St. John. By Roger Fenton, from a carving in yellow house-stone by Albert Durer. Nothing can exceed the truthfulness of this picture in its present state, the yellow tone it has assumed being an improvement. I fear, however, that peculiar tint forebodes future decay.