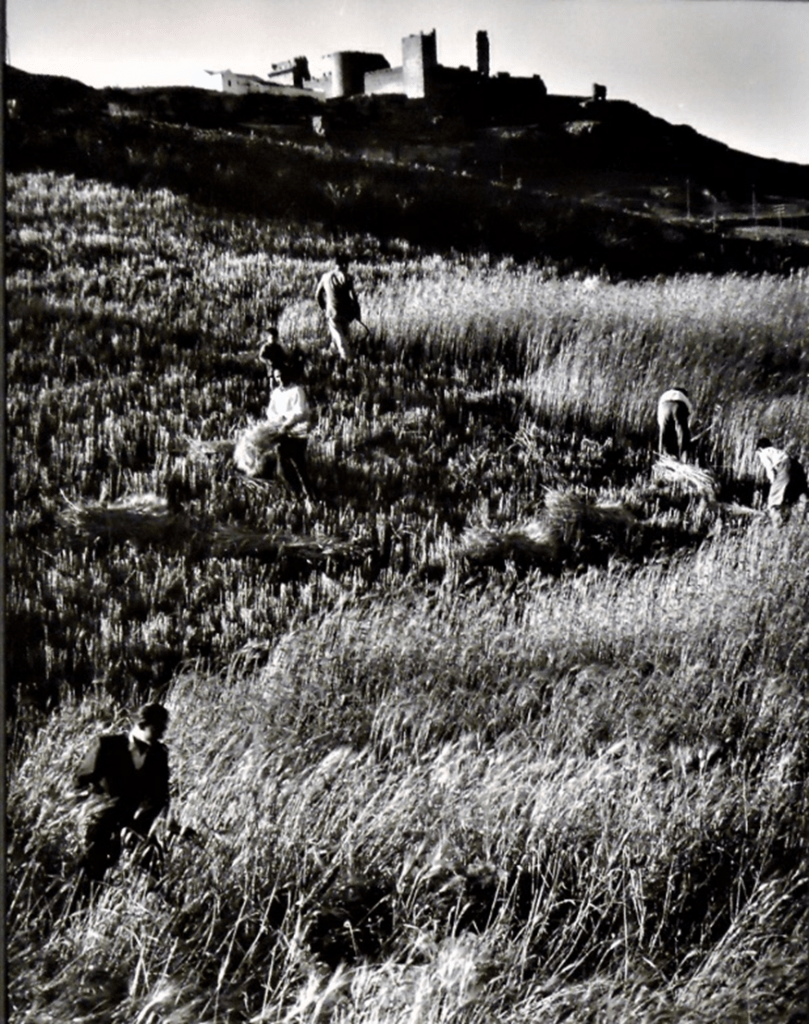

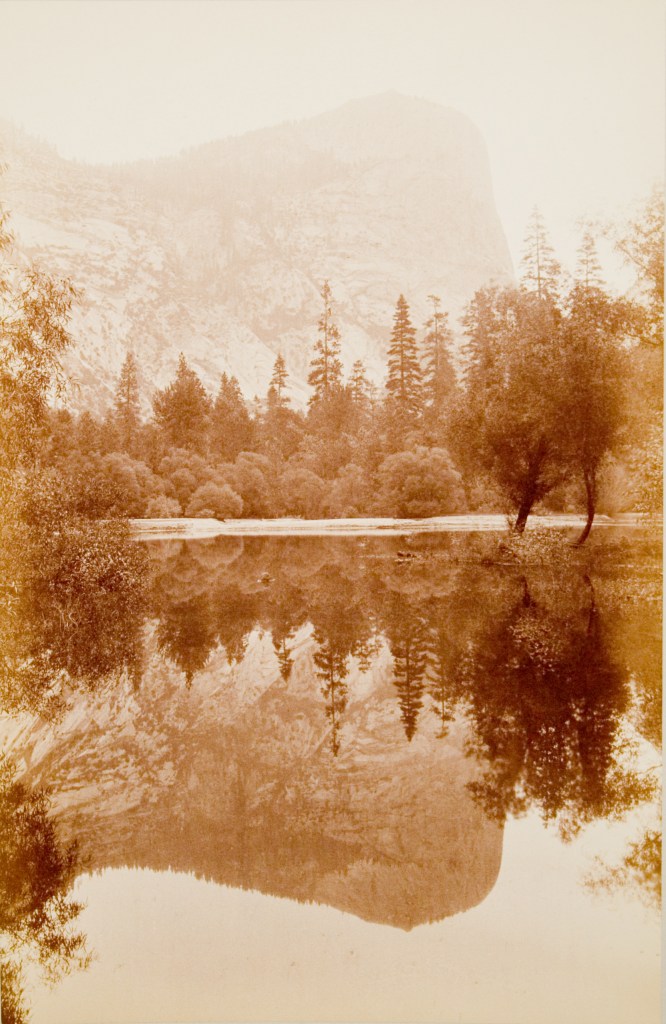

Pohono, the Bridal Veil Fall, Yosemite. 900 ft. Ca. 1865-66.

[I acquired these prints in Cambridge. MA in the early 1970s. I didn’t bother to identify the maker until the 1990s. I just finished compiling the bibliography in 2024. I do not pretend to be a Watkins expert, but I think that these prints most resemble those found in the Watkins’ 1865 album now in the Syracuse University Library. See: Doherty, Amy S., “Carleton E. Watkins, Photographer: 1829 ‑ 1916.” The Courier: Syracuse University Library Associates 15:4 (1978): 3‑20, plus cover. 5 b & w. WSJ]

WATKINS, CARLETON EUGENE. (1829-1916) BIBLIOGRAPHY.

By William S. Johnson.

(Please credit the blog if you use this bibliography.)

(POSTED March 2024)

[I have compiled and now posted this bibliography to test my belief that current technologies have made it possible to develop a very flexible research tool that can permit a scholar to access a wider range of information and provide a more nuanced look into the functioning of any particular era in the history of photography. This bibliography is composed from the Nineteenth-Century Photography. An Annotated Bibliography 1839-1879, by William S. Johnson. Boston: G. K. Hall & Co., 1990, to which I’ve added a key-word search of my current bibliographic project of indexing more than 800 periodical titles published in the USA and England between 1835 and 1869. After 1869 additional references were drawn from other random projects or sources that I had on hand and a key-word literature search of the internet. Not every important source is on the internet and it should not be considered an exhaustive survey of the literature published after that date. WSJ]

************************************************************************************************************************

Carleton E. Watkins began his long and extraordinary photographic career in 1854, in one of Robert Vance’s daguerreotype galleries in California. Watkins was born and grew up in Oneonta, New York, then moved in 1851, at age 22, to California. Watkins worked as a carpenter and clerk first in Sacramento, then in San Francisco before he became a temporary replacement for an employee who had abruptly left one of Vance’s branch studios. Given hasty instructions in the complicated daguerreotype process and asked to stall the patrons for a week until a regular “operator” could be found, Watkins quickly turned into a competent, then excellent, photographer. Watkins spent the next few years working for Vance and in other galleries making daguerreotype and then ambrotype portraits.

By 1856 photographers were experimenting with the new wet collodion process, which made taking landscape views a much more feasible, practical and economical activity. Carleton Watkins learned the new process and by 1858 was using it to photograph views to provide visual documentation for a court settlement of land disputes. For several years Watkins made a reasonable living taking these kinds of documents for litigants, at the same time perfecting his “field” skills and establishing his reputation as a field photographer.

By 1861 he had his own studio, but he specialized in views and travelled throughout California. Made his first trip to Yosemite in 1861 and returned many times in the 1860s. In 1867 Watkins photographed the Oregon and Columbia River region. He opened the Yosemite Art Gallery in 1867.

Attribution for many 19th century photographs is very difficult, as common practice was for gallery owners to attach their name (their brand) to photos made by employees or associates or even to negatives sold to them by other photographers. (Or, occasionally, as with Mathew Brady, even though illegally copying them.) In the late 1860s Watkins acquired the negatives of about 340 stereo views of the construction of the Central Pacific Railroad, which had been made by Alfred A. Hart, a Sacramento photographer, and Watkins then reissued the stereos under his own name. * [* See Alfred A. Hart post on this website.] Watkins also obtained a small series of stereoscopic negatives relating to the Modoc War made by Louis Heller, a photographer of Fort Jones, California, and issued those under his own name as well. Later, I. W. Taber acquired Watkins’ own early negatives of Yosemite when Watkins went bankrupt in 1874 and Taber then printed them under his own name throughout the 1870s and 1880s.

Watkins reopened his practice and rephotographed Yosemite. There must have been some irony present when both photographers separately displayed Yosemite photographs at various international exhibitions.

One way of building a reputation was by exhibiting at the various County or State Fairs or even at the international exhibitions patterned after famous World’s Fair in London in 1851. Watkins started exhibiting at the California State Fairs, but he soon began submitting his photographs to the large international expositions. A small sample of his work was submitted to the Exposition in London in 1862, arriving too late to be officially “listed” but attracting wide critical notice when they were hung. He then exhibited in the Universal Exposition at Paris in 1867, in Vienna in 1873, and in the United States Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876. Watkins also submitted work to the leading photographic magazines of the day. The strength of his work, seen by thousands through these venues, built Watkin’s a rare international reputation, but the labor and time and expense involved for an individual – not a corporate gallery – may have proved costly.

Commissioned to photograph the estate of Thurlow Lodge in Menlo Park from 1872 to 1874, Watkins produced a large body of work on this subject. For the next twenty years Watkins would travel all over the American West, taking tens of thousands of photographs -most of them good, serviceable documents of the Western landscape and the changes that it was undergoing -and a surprising number of them moving into the realm of creative expression. Watkins continued to photograph into the 1890s, but age and ill health slowed him down. His studio and its contents were completely destroyed in the San Francisco earthquake of 1906, and Watkins was severely affected by the loss of his work. He died, blind and incapacitated, in 1916.

BOOKS

1863

Langley, Henry G. The San Francisco Directory for the Year Commencing October, 1863: Embracing a General Directory of Residents And Business Directory: Also, a Directory of Streets, Public Offices, Etc., and a New Map of the City and County; Together With The Consolidation Act and its Amendments; the Municipal Government; Societies and Organizations, and a great Variety of Useful and Statistical Information, Exhibiting at a Glance the Progress and Present Condition of the City. “Sixth Year of Publication.” San Francisco: Towne & Bacon, Book and Job Printers, 1863. 592 p.; ill., map. 23 cm.

[“San Francisco [W] Directory.”

Watkins, Carleton E. photographer 649 Clay (p.366)]

(Etc., etc.)

San Francisco Business Directory.

Daguerreian, Ambrotype, and Photographic Materials.

Bradley H. W. 622 Clay

Shew W. 423 Montgomery

Daguerreians.

Bayley W. F. 622 Kearny

Bryan & Johnston, 611 Clay

Dyer Wm. D. 612 Clay

Edouart A. 634 Washington

Hamilton & Shew, 417 Montgomery

Higgins T. J. 659 Clay

Hills R. 683 Market

Hord J. R. 11 Third

Johnson G. H. 619 Clay

McGinn A. Miss, 234 Kearny

Selleck S. 413½ Montgomery

SHEW W. 423 Montgomery (see advertisement, p. 530)

Silva J. T. 703 Clay

(Etc., etc.)

[See Photographic Galleries.] (p. 410)

Photographic Galleries.

Bradley & Rulofson, Vance’s, 429 Mont

Gibbons H. 6 Montgomery

Suckert J. 306 Dupont

Bryan & Johnston, 611 Clay

Bush H. 9 Post

DYER W. D. 612 Clav (see adv. p. 561)

Edouart A. 634 Washington

Hamilton & Shew, 417 Montgomery

Higgins T. J. 659 Clay

Johnson G. H. 645 and 649 Clay

Selleck S. 415 Montgomery

SHEW W. 423 and 425 Montgomery

(see advertisement p. 530)

Silva T. J. 703 Ciay

(See Daguerreians.) (p. 429)

Watkins, Carleton E. Yo‑Semite Valley: Photographic Views of the Falls and Valley of Yo‑Semite in Mariposa County, California. San Francisco, CA: Bartling & Kimball, 1863 [1866?] n. p. 65 l. of plates. 65 b & w. [Album, of original photographs, bound by the publisher. Syracuse Univ. Library.]

Whitney, J. D. Notice of the Two Masses of Meteoric Iron Brought from Tucson To San Francisco, 1862 and 1863. San Francisco: Printed by Towne & Bacon, Book and Job Printers, No. 636 Clay Street, opposite Leidesdorfl. 1863. 12 p. 8 vo.

[“Head Quarters Column from California,

Tucson, Arizona, June 30th, 1862.

To General George Wright, U. S. Army,

Commander Dep. of the Pacific, San Francisco, Cal.

My dear General:—Soon after my arrival at this place I sent by a train to Port Yuma, to be shipped to your address at San Francisco, a very large and beautiful Aerolite, which I found here and which I had heard and read of for many years. In Bartleit’s Explorations, vol. 2, page 297, it is described as follows: “In the afternoon,” July 18th, 1853, “I called to take leave of General Blanco, and at the same time examine a remarkable meteorite, which is used for an anvil in a blacksmith’s shop. This mass resembles native iron, and weighs about six hundred pounds. Its greatest length is five feet. Its exterior is quite smooth, while the lower part which projects from the larger leg is very jagged and rough. It was found about twenty miles distant on the road towards Tubac and about eight miles from the road.” I desire that you present this aerolite to the City of San Francisco, to be placed upon the Plaza, there to remain for the inspection of the people and for (p. 6) examination by the youth of the city forever. It will be a durable memento of the march of the Column from California. I am, General, sincerely and respectfully, Your friend and servant, James H. Carleton, Brigadier General U. S. A.

Soon after this mass of meteoric iron came into the possession of the city, I obtained permission from the Board of Supervisors to have sawn from it a small piece for analysis and for distribution to a few of the principal public institutions in this country and Europe having collections of aerolites; this has been done, and also a fine photograph of it taken by Mr. C. E. Watkins, of which copies will be forwarded, with the specimens of the mass itself, as convenient opportunity offers….” (p. 7) (Etc., etc.)

“…At present the mass in question lies upon the steps of the Custom House, where it has been most admirably photographed by Mr. Watkins.* [* The mass was shipped on the Panama steamer, which sailed from San Francisco on the 3d of August,] It was said by Mr. Ainsa to weigh 1,600 pounds. The shape of this meteoric mass is very peculiar; and, at first, it would hardly be recognized as the identical specimen figured by Mr. Bartlett at Tucson, especially as this gentleman estimated its weight at 600 pounds only….” (p. 10) (Etc., etc.)

“…The photograph was taken by Mr. Watkins, at my request, partly to be sent abroad as a specimen of the high degree of perfection which has been attained by this gentleman in this department of art, and partly that an exact representation might be secured of this very remarkable body, in case it should be lost or captured on its way to Washington.” (p. 10)]

1865

Across the Continent: A Summer’s Journey to the Rocky Mountains, the Mormons, and the Pacific States, With Speaker Colfax. By Samuel Bowles, Editor of the Springfield (Mass.) Republican. Springfield, Mass.: Samuel Bowles & Company. New York: Hurd & Houghton., 1865. xx, 452 p. front. (folded map) 19 cm.

[“Introductory Letter to the Hon. Schuyler Colfax.”

“…In Natural Wonders and Beauties, as in rare gifts of wealth, the country of our Summer Journey stands out prominent and pre- eminent. Neither the Atlantic States nor Europe offer so much of the marvellous and the beautiful in Nature; offer such strange and rare effects, such combinations of novelty, beauty and majesty,– as were spread before us in our ride Across the Continent, through the mountains, and up and down the valleys. No known river scenery elsewhere can rival that of the Columbia, as it breaks through the Continental mountains; no inland seas charm so keenly as Puget’s Sound; no mountain effects are stranger and more impressive than those the Rocky and the Sierras offer; no atmosphere (p. vii) so fine and exhilarating, so strange and so compensating as California’s; no forests so stately and so inexhaustible as those of Washington; no trees so majestic and so beautiful as the Sequoia Gigantea;-aye, and no Vision of Apocalypse so grand, so full of awe, so full of elevation, as the Yosemite Valley! Does not that vision, that week under the shadows of those wonderful rocks,-by the trickle and the roll of those marvelous water-falls,-stand out before all other sights, all other memories of this summer, crowded as it is with various novelty and beauty? The world may well be challenged to match, in single sweep of eye, such impressive natural scenery as this. Professor Whitney tells us that higher domes of rock and deeper chasms are scattered along the Sierras, farther down the range; but he also testifies that, in combination and in detail, in variety and majesty and beauty of rock formations, and in accompanying water-falls, there is no rival to, no second Yosemite. You will be interested in Professor Whitney’s more detailed account of the Valley, and his suggestions as to its creation, which are appended to my Letters. They are from his just issued second volume of the Reports of the Geological Survey of California, which, if suffered to be completed as begun, will present a complete scientific account, in aggregate and in detail, of that wonderful State, and be the guide to all her future development.

The Yosemite Valley ought to be more known in the East, also, through the marvelous photographs of Mr. Watkins of San Francisco; he has made a specialty of these views, and, besides producing the finest photographs of scenery that I know of anywhere, he gives to those who see them very im- pressive ideas of the distinctive features of this really wonderful valley….” (p. viii) (Etc, etc.)

Geological Survey of California. Geology. Volume I. Report of Progress and Synopsis of the Field-Work, from 1860 to 1864. [Sacramento:] Published by Authority of the Legislature of California. 1865. xviii, 498 p.: ill., plates. [Illustrations are 9 full-page, tipped-in, “plates,” and 81 “figures,” which are illustrations withIn the body of the texts. All are engravings, some obviously after photographs, but not necessarily credited. WSJ]

“…The valley is a nearly level area, about eight miles in length and varying from half a mile to a mile in width. For the lower six miles its course is from northeast to southwest; the upper two miles are nearly at right-angles to this, the angle of the bend being at the spot where the Yosemite Fall comes over the precipice on the north side. Below the expanded portion of the valley, the Merced enters a terribly deep and narrow cañon, which is said to be inaccessible, and which we had no time to explore.

To make the peculiar features of the Yosemite more intelligible to those who have not seen it, or who have not enjoyed, what is next best to the thing itself, the admirable photographs of Mr. C. E. Watkins,* [*These photographs, thirty in number, and twenty-one inches by sixteen in size, are pronounced by all artists to be as near perfection as possible. They are already well known and widely distributed through the Eastern States, and will be more so. The glass stereographs taken in the valley, by Mr. Watkins, are in some respects even more effective than the photographs. All the views of the Yosemite given in this volume are taken from these photographs, by permission.] we give a wood-cut (Fig. 62), representing a portion of both sides of the valley, and which is one of the first near views which the traveller gets of the grander masses, whether he descends by the Coulterville or the Mariposa trail. On the right-hand or south side (the view being taken looking up, or to the northeast), we have the cliffs on the face of which the Bridal Veil Fall is seen. Behind this is a much higher mass, which forms a portion of the Cathedral Rock. On the other side is Tutucanula, or El Capitan, the first of these names being the original Indian appellation for this mighty cliff, and supposed to be either the name of some great chief, or else the word by which their “Great Spirit” or Deity was called, while “El Capitan” is the term by which the first visitors to the valley undertook to translate the aboriginal idea into the Spanish. As the idea of the dimensions and verticality of the walls of the Yosemite may be somewhat less easily taken from the shaded woodcut, a section (Fig. 63) is appended of the valley at this point, on an (p. 408) (Etc., etc.)

“…it is especially fine in the direction of the Obelisk Group of mountains, and it commands the cañon of the south fork of the MercedIllilouette,” as it is called by the Indians. From this point the glacial phenomena, and especially the regular and extensive moraines, of that valley are finely displayed. The profile of the Half Dome, of which more farther on, is best seen from the Sentinel Dome. From near the foot of Sentinel Rock, looking directly across the valley, we have before us, if not the most stupendous feature of the Yosemite, at least the most attractive one, namely the Yosemite Fall. We have endeavored to convey some idea of the grandeur and beauty of this fall, by reproducing (in Plate 2) as well as can be done on the small scale allowable in this volume and on wood, one of Mr. Watkins’ photographs; but it is in vain that we attempt, by any work of art, to do more than give the faintest echo of the impression which this glorious exhibition of nature produces on all who are so fortunate as to see it under favorable circumstances. About the time of full moon, and in the month of May, June, or July, according to the dryness and forwardness of the season, is the time to visit the Yosemite, and to enjoy in their perfection the glories of its numerous water-falls. Those who go later, after the snow has nearly gone from the mountains, see the streams diminished to mere rivulets and threads of water; they feel satisfied with the other attractions of the valley, its stupendous cliffs, domes and cañons, and think that the water-falls are of secondary importance, and that they have lost little by delaying the time of their visit. This is not so; the traveller who has not seen the Yosemite when its streams are full of water has lost, if not the greater part, at least a large portion, of the attractions of the region, for so great a variety of cascades and falls as those which leap into this valley from all sides has, as we may confidently assert, never been seen elsewhere -both the Bridal Veil and the Nevada Fall being unsurpassed in some respects, while the Yosemite Fall is beyond anything known to exist, whether we consider its height or the stupendous character of the surrounding scenery. The Yosemite Fall is formed by a creek of the same name, which heads on the west side of the Mount Hoffmann Group, about twenty miles north of the valley….” (p. 413) (Etc., etc.)

“…The North Dome, on the opposite side of the valley of Tenaya Creek, is another of these rounded masses of granite, of which the concentric structure, already frequently alluded to in this chapter, is very marked. The annexed wood-cut (Fig. 68), engraved by Mr. * [Fig. 68. North Dome-Yosemite Valley.] Andrews from one of Watkins’s photographs, will illustrate both the form of the dome and its structure. It is 3568 feet in elevation above the valley, and is very easy of ascent from the north side. At the angle of the cañon, appearing as a buttress of the North Dome, is the Washington Column, a grand, perpendicular mass of granite, and by its side the Royal Arches, an immense arched cavity formed in the cliff’s by the giving way and sliding down of portions of the rock, the vaulted appearance of the upper part of it producing a very fine effect. Farther up the cañon of Tenaya Creek is a little lake, called Tis (p. 417)

“…and the whole character of the scenery which surrounds it, Mount Broderick alone being an object of which [Fig. 69. Mount Broderick and the Nevada Fall] the fame would be spread world-wide, if it were not placed as it is, in the midst of so many other wonders of nature. There are also grand cascades in the South Fork Cañon, the scenery through the whole of which is little inferior to that of the other portions of the Yosemite; but, amid so many objects of attraction, few visitors find time to examine this cañon, especially as the trail by which it is reached is a rough and difficult one. Judging from Mr. Watkins’s photographs, the views from points along the slopes of the South Fork Cañon must be equal to almost any which can be had in the whole region. In the angle formed by the Merced and the South Fork Canon, and about two miles south-southeast of Mount Broderick, is the high point, called the “South Dome,” and also, of later years, “Mount Starr King.” (p. 419) (Etc., etc.)]

[Fig. 62. Yosemite Valley. (p. 409)

Fig. 63. Section across the Yosemite. “El Capitan” “Bridal Veil” (p. 409)

Fig. 64. Cathedral Rock.” (p. 411)

Fig. 65. Sentinel Rock. (p. 412)

Fig. 66. The Half Dome. Yosemite Valley. (p. 415)

Fig. 67. Section through the Domes. “North Dome Lake Half Dome.” (p. 416)

Fig. 68. “North Dome – Yosemite Valley. (p. 417)

Fig. 69 “Mount Broderick and the Nevada Fall.” (p. 419)

[From Watkins’ photographs.]

[Plate I. Consists of drawings of fossilized sea shells, and is located before p. 481 in: “Appendix B. Description of Fossils from the Auriferous Slates of California.” By F. B. Meek. (p. 477-483)]

Plate II, Before p. 413. Under the Yosemite Fall.

Plate III, p. 415. The Canon of the Merced and the Vernal Fall.

Plate IV, p. 425. The Obelisk Group from Porcupine Flat.

Plate V, p. 427. Upper Tuolumne Valley from Soda Springs, Looking South.

Plate VI, p. 429. “Cathedral Peak Group Upper Tuolumne Valley.”

Plate VIII, Pp. 434.” Crest of the Sierra, Looking East from Above Soda Springs.”

Plate IX, p. 446. “Volcanic Ridges Near Silver Mountain.”

[Plates II and III definitely by Watkins, some others possibly. WSJ]

1866

Watkins, Carleton E. Yo‑Semite Valley: Photographic Views of the Falls and Valley of Yo‑ Semite in Mariposa County, California. San Francisco, CA: Bartling & Kimball, 1863 [1866?] n. p. 65 l. of plates. 65 b & w. [Album, of original photographs, bound by the publisher. Syracuse Univ. Library.]

1867

Hall, Edward H. Appletons’ Hand-Book of American Travel. Containing a Full Description of the Principal Cities, Towns, and Places of Interest: Together with the Routes of Travel and Leading Hotels Throughout the United States and British Provinces. Illustrated With Copious Maps. “Ninth Annual Edition.” New York: D. Appleton & Co., 443 & 445 Broadway. London: Trübner & Co. 1867. 1 v. (various pagings), [9] folded leaves of plates: maps, plans; 29 cm.

[“ “Obligations.”

“Our obligations are due to the entire United States and Canadian Press for their unceasing endeavors to keep us informed of the rapid changes transpiring in their respective localities, as well as for their numerous contributions to local and state history, descriptive sketches, etc., etc. Below will be found a list of authorities referred to in the work.

We are specially indebted to Mr. C. E. Watkins,* [* Views of the Yo-Semite Valley by this clever artist can be obtained in New York of the editor.] and Messrs. Lawrence and Houseworth, of San Francisco, for their fine pictures of scenery in California and on the Pacific coast; to Mr. Edward Vischer, of San Francisco, for his fine collection of drawings in the same region; to Messrs .Savage and Ottinger, of Great Salt Lake City; to Mr. Eugene Piffet, of New Orleans; Mr. Sancier, of Mobile; Mr. Linn, of Chattanooga, and other photographic artists throughout the Union who have kindly furnished us with views of prominent objects of interest in their several localities. We regret that lack of time and space compel us to exclude their contributions from our pages. It is decided to make future issues of the Hand-book uniform in style and appearance with the present work.

For much valuable information contained in the following pages we are indebted to the recently-published Directories of New York, Philadelphia, Boston, New Orleans, Baltimore, Mobile, Cincinnati, Memphis, Chicago, St. Louis, San Francisco, Albany, Milwaukee, Richmond, Va., St. Paul, Virginia City, Nevada, Portland, Oregon, and Austin, Nevada.

We are also under obligations to Mr. A. Gensoul, of San Francisco, for a set of his recently published maps. Thankful to one and all for their valuable assistance, we shall endeavor to merit a continuance of their favors. Authorities Referred To In The Work

Arizona and Sonora, by Sylvester Mowry.

Speeches and Letters of Governor Richard C. McCormick.

North Carolina, Historical Sketches of, by John H. Wheeler.

California Guide, etc., by J. M. Hutchings.” (p. xv.)]

Report of the Commissioner to the Universal Exposition at Paris, 1867.

Notes upon the Universal Exposition at Paris, 1867, by William P. Blake. (pp. 249-347)

Chapter I.

General View of the Paris Exposition of 1867.

The Building.

The general plan and arrangement of the Universal Exposition of eighteen hundred and sixty-seven was the result of the observation and experiences of the former great International Exhibitions at London in eighteen hundred and fifty-one, at Paris in eighteen hundred and fiftyfive and at London in eighteen hundred and sixty-two. In those Exhibitions grand architectural effect were attempted, and large sums were expended in exterior and interior decoration. In the Exhibition building of eighteen hundred and sixty-seven all architectural display was subordinated to the convenience of grouping and display of the various objects contributed. The leading feature of the plan was the division of the space into seven concentric galleries, each one devoted to a particular group or class of objects…. (p. 255)

List of Groups, With the Classes Attached.

Groups. Class.

Group I. — Works of Art.

Paintings in oil 1

Other paintings and drawings 2

Sculpture and dye-Sinking 3

Architectural designs and models 4

Engraving and lithography 5

Group II. — Apparatus and Application of the Liberal Arts.

Printing and books 6

Paper, stationery, binding, painting and drawing materials 7

Applications of drawing and modelling to the common arts 8

Photographic proofs and apparatus 9

Musical instruments 10

Medical and surgical instruments and apparatus 11

Mathematical instruments and apparatus for teaching science 12

Maps and geographical and cosmographical apparatus 13 (p. 258)

The Park.

The visitor to the Exhibition was at once forcibly impressed with the importance and extreme interest of the Park as part of the Exhibition. It was most tastefully laid out with avenues and winding paths, and was adorned with trees, shrubs and flowers, all planted since the ground was first broken for the foundation of the Palace, on what was previously the barren and indurated surface of the Champs de Mars.

“…Alongside of this building there was a pleasing vista over green lawns and parterres of flowers to the American annexe beyond, where could be seen the beautiful locomotive and various agricultural machines. On the left of the avenue was a building for the display of windows of stained and painted glass, to which the art of photography had lent its aid. Portraits and photographs were there reproduced in all the brilliance and permanence of color of stained glass. In continuing a walk toward the entrance of the building, the visitor…” (p. 262)

Distribution of Prizes.

The work of the juries commenced as soon as the Exhibition opened, and the awards were made very soon thereafter, and in many cases before some of the contributions were fairly placed and labelled. The grand ceremony of the distribution of prizes was on the first of July, at the Palace of Industry, the building erected for the Exhibition of eighteen hundred and fifty-five. The recipients of grand prizes and gold medals received them from the hands of the Emperor, in the presence of seventeen thousand spectators, all comfortably seated in that magnificent hall…”

“…The prizes awarded to exhibitors from California were as follows:

State of California* [*The official announcement of this award reads: “Le Gouvernment de California — Céréals.”

As the State of California was not an exhibitor, this destination of the award is apparently the result of misapprehension. The exhibitors of cereals were Mr. D. L. Perkins, Mr. J. W. H. Campbell and Mr. J. D. Peters. The display made by Mr. Perkins included one hundred and twenty varieties of seeds, neatly arranged in glass bottles and labelled, and, together with the photograph, was the most prominent. It is the opinion of the Commissioner that the medal should either be given to Mr. Perkins or to the exhibitors of cereals jointly.] —Cereals. Silver medal.

Dr. J. B. Pigné, San Francisco—Collection of California minerals. Silver medal.

William P. Blake, California—Collection of California minerals. Silver medal. (p. 265)

Mission Woollen Mills, San Francisco—Exhibition of blankets, cloths and flannels. Bronze medal.

C. E. Watkins, San Francisco— Photographs of Yosemite Valley. Bronze medal.

Brown & Level, California—Self-detaching boat tackle. Bronze medal.

Buenavista Vinicultural Society—Sparkling wine. Honorable mention….” (p. 266)

Woods and Products of the Forest.

France.

The forest products and industries of nearly every country were represented in the Exposition, by sections of trees, planks, boards, mouldings, etc., and by collections of the tools used for cutting, hewing and sawing. Of all these collections, that made by France, through the “Administrator of the Forests,” was the most complete, methodical and interesting. It occupied a space about sixty feet in length, in the second gallery, devoted to Group V, and was very tastefully displayed. Sections of all the principal kinds of trees in the Empire were ranged along the wall with the interspaces filled with green moss. Each section of a tree was about six inches thick, and included the bark, so that the whole structure and outer form and appearance of the trunk was clearly shown. Above these, on a table which extended around the room, smaller sections and portions of dressed and worked timber were arranged. with herbaria, photographs and drawings of forest trees. The tools used were grouped above, on the wall, around centre pieces, formed of boar’s heads. In the centre of the room a broad table sustained various models of forests and of sawmills, and of apparatus used in felling and transporting timber. There were also models of the buildings erected for the keepers’ lodges, and of cottages for the laborers. Some of the plans in the relief exhibited the important operations of the administration of forests, such as the replanting of the Alps. A large forest chart upon the wall, of France, showed in the most striking manner the distribution of the wooded parts of the country and the relation which exists between them and the geological constitution of the soil. The whole collection was completed by a series of specimens of the various destructive forest insects.

There was also a series of publications on practical or scientific questions, relating to sylviculture, and a fine collection of photographs of cones and foliage of the various pines and firs….“ (p. 267)

The Forest Products of Canada.

Canada made a very respectable show of its resources in lumber of various kinds. There were sections of the principal trees, with their bark, in great number. They were usually about two feet long, and were super-imposed one upon another, so as to make a base for several columns of square logs, of different woods for building purposes, set up about eight feet apart. These supported above a square timber of yellow pine, fifty feet long and ten feet square. The niches formed by this disposition of the timber were filled with smaller specimens, and by panels of dressed and polished planks of pine, white wood, walnut and birch. The Abbé Brunet, of Quebec, Canada, sent a fine collection of Canadian woods, with herbaria and a series of photographs of trees and of plantations. He made the whole complete and instructive by a printed catalogue of sixty-four pages, which contained a large amount of valuable information upon the trees of Canada. This collection, for its uniformity, neatness and pleasing appearance, was one of the most attractive in the Exhibition, and it received a gold medal. (p. 269)

Suez Canal.

The progress of the great Suez Canal was fully illustrated in a separate building in the Park by a large model, a panorama, photographs, and miscellaneous collections. The model of the Isthmus was a complete miniature representation of the country, with all its elevations and depressions, on a scale of one to five hundred thousand….” (p. 318)

List of Exhibitors of Objects from California at the Paris Exposition.

Names and Articles Exhibited. Group. Class.

MISSION WOOLLEN MILLS, San Francisco, Lazard Fréres,Agents. Four cases of woolen goods, manufactured in California from California wool. IV 30

C. H. HARRISON, San Francisco. Centrifugal pump …. …..

C. E. WATKINS, San Francisco. Series of twenty-eight large photographic views of Yosemite Valley, and two of the Big Trees of the Mariposa Grove II 9

LAWRENCE & HOUSEWORTH, San Francisco. Twenty-six large photographs of Yosemite Valley and of the Great Trees, and three hundred stereoscopic views of different localities in California. II 9

EDWARD VISCHER, San Francisco. One case containing six portfolios of views in California and Washoe. II 9

A. S. HALLIDIE & CO., San Francisco. Samples of wire rope, round

and flat, and iron and copper sash cords of California manufacture. V 40

PACIFIC GLASS WORKS, San Francisco. Specimens of California

made glass bottles. III 16

JOHN D. BOYD, San Francisco. One highly finished ornamental door, made of wood grown in California. III 14

JOHN D. BOYD, San Francisco Specimens of -the wood of the Madrona, or California laurel V 41

JOHN REED, San Francisco. Premium tank lifeboat model, four feet long. VI 66

SAN LORENZO PAPER MILLS Varieties of paper made at the company mills in Santa Cruz, California. …. ….

STANDARD SOAP COMPANY. Specimens of California made soap and washing powders …. …. (p. 336)

D. L. PERKINS, San Francisco and Oakland. Collection of seeds grown in California, and a photograph of California vegetables.

(Donated to the Imperial Garden of Acclimatation.) VII 67

J. W. H. CAMPBELL, San Francisco. One case — about one hundred and twenty pounds — California high mixed wheat.

(Donated to Royal Agricultural Society, England) VII 67

J. D. PETERS, San Joaquin County. One box containing about thirty pounds of wheat VII 67

BUENA VISTA VINICULTURAL SOCIETY (by R. N. Van Brunt, Secretary). Cases of sparkling wine made from grapes grown at the Society’s vineyard, Sonoma County, California, 1865 VII 73

C. H. LE FRANC, New Almaden Vineyard. Four cases of red and white wines made in San José, California. VII 73

SANSEVAIN BROTHERS, Los Angeles. One case of California wine VII 73

KOHLER & FROHLING. California wines. VII 73

M. KELLER, Los Angeles. Four cases of California wines.

A. FENKHAUSEN, San Francisco. Three cases California wine and bitters. VII 73

TAYLOR & BENDEL, ‘San Francisco. One case of stomach bitters. VII 73

Dr. J. PIGNÉ San Francisco. Six cases of California and Nevada minerals and ores.

(Donated to the School of Mines, Paris) V 40

CALIFORNIA STATE AGRICULTURAL SOCIETY. Volumes of the Society’s reports for distribution. V 40

WILLIAM P. BLAKE, San Francisco. Collection of California minerals and ores. (See list of minerals and ores.) V 40

DRS. HARKNESS and FREY, Sacramento. Large mass of silver ore from Blind Springs, Mono County, California, weighing about one hundred pounds V 40

————————————— (p. 337)]

Whitney, Josiah Dwight, State Geologist. Geological Survey of California. The Yosemite Guide-Book: A Description of the Yosemite Valley and the Adjacent Region of the Sierra Nevada, and of the Big Trees of California, Illustrated by Maps and Woodcuts. Published By Authority of the Legislature. (Sacramento]: 1870. viii, 155 p. illus. 8 plates, fold maps. 24 cm.

[“Prefatory Note. A statement of the way in which the present volume came to be authorized by the Legislature, and of the sources from which the information it contains was drawn, will be found in the introductory chapter. It may be proper to add, that two editions of the work have been published, one in quarto form, with photographic illustrations, the other (the present volume, namely), with wood-cuts. These cuts have been selected from among those used in the first volume of our “Geology of California.” The maps are the same in both editions, and the text also, except that some verbal changes have been made, and a few pages added, in this edition, relating to that portion of the High Sierra which lies near the head of the Kern, King’s, and San Joaquin Rivers. J. D. W. Cambridge, Mass., May 1, 1869. (p. viii)

[There are 8 full-page “plates” tipped in and 20 “figures” (primarily engraved landscapes) in the text pages. See Geology of California for titles. WSJ]

Whitney, Josiah Dwight, State Geologist. Geological Survey of California. The Yosemite Book. A Description of the Yosemite Valley and the Adjacent Region of the Sierra Nevada, and of the Big Trees of California. Illustrated by Maps and Photographs. New York: Julius Bien, 1868. 116 pp. 28 l. of plates. 28 b & w. [Twenty‑eight photographs, four by W. Harris, the remainder by Carleton E. Watkins. Photographic edition limited to 250 copies. NYPL, GEH collections.]

Transactions of the California State Agricultural Society During the Years 1866 and 1867.

Sacramento: D. W. Gelwicks, State Printer, 1868. 640 p.

[“ Report Upon the Universal Exposition at Paris, 1867.

Chapter I.

General View of the Paris Exposition of 1867.

The Building.

The general plan and arrangement of the Universal Exposition of eighteen hundred and sixty-seven was the result of the observation and experiences of the former great International Exhibitions at London in eighteen hundred and fifty-one, at Paris in eighteen hundred and fifty-five and at London in eighteen hundred and sixty-two….” (Etc., etc.) (p. 255)

List of Groups, with the Classes Attached.

Groups.

Group I.-Works of Art.

Paintings in oil………………..

Other paintings and drawings….

Sculpture and dye-sinking…….

Architectural designs and models……

Engraving and lithography….

Group II.-Apparatus and Application of The Liberal Arts.

Printing and books……..

Paper, stationery, binding, painting and drawing materials…….

Applications of drawing and modelling to the common arts….

Photographic proofs and apparatus…..

Musical instruments…….

Medical and surgical instruments and apparatus……

Mathematical instruments and apparatus for teaching science…..

Maps and geographical and cosmographical apparatus..

Group III.-Furniture and Other Objects For The Use of Dwellings.

Fancy furniture……..

Upholstery and decorative work.

Crystal fancy glass and stained glass….

Porcelain, earthen ware and other fancy pottery..

Carpets, tapestry and other stuffs for furniture….

Paper hangings…….

Cutlery……

Gold and silver plate……

Bronzes and other art castings and repoussé work..

Clocks and watches……..

Apparatus and processes for heating and lighting..

Perfumery…………

Leather work, fancy articles and basket work……

Group IV.—Clothing (Including Fabrics) and Other Objects Worn On The Person.

Cotton thread and fabrics…..

Thread and fabrics of flax…….

Combed wool and worsted fabrics…

Carded wool and woollen fabrics…….

Silk and silk manufactures…..

Shawls……Lace, net, embroidery and small ware manufactures…

Hosiery and underclothing and articles appertaining thereto…

Clothing for both sexes……” (p. 258)

Jewellery and precious stones….

Portable weapons………

Travelling articles and camp equipage.

Toys…….

Group V.-Products, Raw and Manufactured, of Mining Industry, Forestry, Etc.

Mining and metallurgy……

Forest products and industries………………..

Products of the chase and fisheries; uncultivated products…

Agricultural products (not used as food)……..

Chemical and pharmaceutical products….

Specimens of the chemical processes used in bleaching, dyeing,

printing, etc…….

Leather and Skins…….

Group VI.-Apparatus and Processes Used In The Common Arts.

Apparatus and processes of the art of mining and metallurgy…..

Agricultural apparatus and processes used in the cultivation of

fields and forests……

Apparatus used in shooting, fishing tackle and implements used

in gathering fruits obtained without culture.……………..

Apparatus and processes used in agricultural works and in works

for the preparation of food……..

Apparatus used in chemistry, pharmacy and in tan yards…..

Prime-movers, boilers and engines specially adapted to the

requirements of the Exhibition…

Machines and apparatus in general……………………….

Machine tools……

Apparatus and processes used in spinning and ropemaking..

Apparatus and processes used in weaving……..

Apparatus and processes for sewing and for making up clothing..

Apparatus and processes used in the manufacture of furniture

and objects for dwellings………

Apparatus and processes used in paper making, dyeing and

printing…….

Machines, instruments and processes used in various works……

Carriages and wheelwrights’ work…..

Harness and saddlery…

Railway apparatus..

Telegraphic apparatus and processes…..

Civil engineering, public works and architecture…..

Navigation and lifeboats……..

Group VII.-Food (Fresh Or Preserved, In Various States of Preparation).

Cereals and other eatable farinaceous products and the products

derived from them…….(p. 259)

Bread and pastry……………….

Fatty substances used as food, milk and eggs.

Meat and fish……

Vegetables and fruit…….

Condiments and stimulants, sugar and confectionery…

Fermented drinks…..

Group VIII.-Live Stock and Specimens of Agricultural Buildings.

Farm buildings and agricultural works……

Horses, asses, mules……

Bulls, buffaloes, etc……

Sheep, goats……

Pigs, rabbits…

Poultry……

Sporting dogs and watch dogs…..

Useful insects……..

Fish, crustace and mollusca…….

Group IX.-Live Produce and Specimens of Horticultural Works.

Hothouses and horticultural apparatus…..

Flowers and ornamental plants……

Vegetables……..

Fruit trees…………….

Seeds and saplings of forest trees…

Hothouse plants……

Group X.-Articles Exhibited With The Special Object of Improving The Physical and Moral Condition of The People.

Apparatus and methods used in the instruction of children………

Libraries and apparatus used in the instruction of adults at home, in the workshop or in schools and colleges…….

Furniture, clothing and food from all sources, remarkable for useful qualities combined with cheapness…….

Specimens of the clothing worn by the people of different countries………

Examples of dwellings characterized by cheapness combined with the conditions necessary for health and comfort….……………………..

Articles of all kinds manufactured by skilled workmen…..

Instruments and modes of work peculiar to skilled workmen….

To each of the first seven of these groups a circle or gallery of the building was arranged thus: Group I-Works of Art-occupied the inner circle or gallery; Group VI-the engines, machines, etc.-were placed in the outer gallery, a portion of which, along the outer side, was devoted to Group VII; and here, for example, were arranged the cereals, (p. 260)

the seeds, dried fruits, wines and liquors.

Group V-Raw and manufactured productions, such as minerals, ores, forest products, etc.-were placed in the gallery adjoining that containing the machinery. By following these galleries the visitor passed in succession among the productions similar in kind of different countries, while by following the avenues the visitor saw in succession the various productions and manufactures of the same country

After the adoption of this system it was decided to devote a portion of the inner circle to antiquities, so arranged as to give an approximate history of the progress of the arts from the earliest periods to the present time. This became a very interesting part of the Exposition to all classes of visitors. Even the pre-historic period was represented by collections of flint and bone implements from the caves and from the lake dwellings of Switzerland. The bronze period was also illustrated, and so on through the great periods of human history to the present age of steel.

The nature of the articles shown in this gallery of the “History of Human Labor” appears more fully by the following enumeration in the classification, by periods, adopted by the Imperial Commission:

First Epoch-Gaul before the use of metal. Utensils in bone and stone, with the bones of animals that have now disappeared from the soil of France, but found with these utensils, and showing the age to which they belong.

Second Epoch-Independent Gaul. Arms and utensils in bronze and stone. Objects in terra cotta.

Third Epoch-Gaul during the Roman rule. Bronzes, arms, Gaulish coins, jewellery, figures in clay; red and black potteries, incrusted enamels, etc.

Fourth Epoch-The Franks to the crowning of Charlemagne (A. D. eight hundred). Bronzes, coins, jewels, arms, pottery, MS. charters, etc.

Fifth Epoch-The Carlovingians, from the commencement of the ninth to the end of the eleventh centuries. Ivory sculptures, bronzes, coins, seals, jewels, arms, MS. charters, etc….” (Etc., etc.) p. 261) (Etc., etc.)

Distribution of Prizes.

A report was presented at this time by M. Rouher, Minister of State and Vice President of the Imperial Commission, enumerating in a general way the principal operations of the Commission and of the Jury, stating the total number of awards and citing some of the great inter-

national advantages derived from the Exposition. The International Jury was composed of six hundred members, chosen from men distinguished in science, industry, commerce and art, and of various nationalities. This Jury awarded:

Grand prizes……. 64

Gold medals….. 883

Silver medals. 3,653

Bronze medals….. 6,565

Honorable mentions. 5,801

The Jury of the new order of prizes awarded twelve prizes and twenty-four honorable mentions. In addition, the Emperor was pleased to confer upon some of the most eminent of the competitors in the Exhibition the Imperial Order of the Legion of Honor. The prizes awarded to exhibitors from California were as follows: State of California*-Cereals. Silver medal.

Dr. J. B. Pigné, San Francisco-Collection of California minerals. Silver medal.

William P. Blake, California-Collection of California minerals. Silver medal….” (p. 265)

Mission Woollen Mills, San Francisco-Exhibition of blankets, cloths and flannels. Bronze medal.

C. E. Watkins, San Francisco-Photographs of Yosemite Valley. Bronze medal.

Brown & Level, California-Self-detaching boat tackle. Bronze medal.

Buenavista Vinicultural Society-Sparkling wine. Honorable mention.” (266)]

Chapter IV.

Gold, Silver, Platinum and the Rare Metals.

Gold and Its Ores-California.

The principal mines of California were represented in the collection, as will be seen by reference to the appended catalogue. Although the collection was not as extensive and rich as it should have been, it was very interesting and instructive, and was highly commended for the uniformity of the specimens in size and for the arrangement. The collection sent by Dr. Pigné was also very complete and well classified, and contained specimens from some mines not otherwise represented. …” (Etc., etc.)

“…The large crystalline mass of gold from the Spanish Dry Diggings, (p. 299) California, which was exhibited for a time at San Francisco, in the window of Hickok & Spear, and was photographed by Watkins, is now in Paris, the property of M. Fricot, formerly the owner of the Eureka mine. at Grass Valley. Owing to the difficulty and expense of making this unique specimen perfectly safe in the Exposition, it was not entered there, but M. Fricot took pleasure in showing it freely at his house to those most interested….” (p. 300) (Etc., etc.)

“List of Exhibitors

of Objects from California at the Paris Exposition.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Names and Articles Exhibited. Group. Class.

———————————————————————————————————————————

MISSION WOOLLEN MILLS, San Francisco, Lazard Fréres,

Agents. Four cases of woollen goods, manufactured in

California from California wool.……………………. IV 30

C. H. HARRISON, San Francisco. Centrifugal pump………. IV 30

C. E. WATKINS, San Francisco. Series of twenty-eight large photographic

views of Yosemite Valley, and two of the Big Trees of the Mariposa Grove… II 9

LAWRENCE & HOUSEWORTH, San Francisco. Twenty-six large photographs

of Yosemite Valley and of the Great Trees, and three hundred stereoscopic

views of different localities in California…. II 9

EDWARD VISCHER, San Francisco. One case containing six portfolios of views

in California and Washoe… II 9

A. S. HALLIDIE & Co., San Francisco. Samples of wire rope, round and flat,

and iron and copper sash cords of California manufacture……. V 40

PACIFIC GLASS WORKS, San Francisco. Specimens of California made

glass bottles… III 16

JOHN D. BOYD, San Francisco. One highly finished ornamental door, made of

wood grown in California….. III 14

JOHN D. BOYD, San Francisco Specimens of the

wood of the Madrona, or California laurel…….. ….. V 41

JOHN REED, San Francisco. Premium tank lifeboat model, four feet long…….. VI

SAN LORENZO PAPER MILLS. Varieties of paper made at the company’s

mills in Santa Cruz, California…… VI 66

STANDARD SOAP COMPANY. Specimens of California made soap and

washing powders. VI 66

——————————————————————————————————————————— (p. 336) (Etc.,etc.)]

1870

Transactions of the California State Agricultural Society During the Years 1868 and 1869. Sacramento: D. W. Gelwicks, State Printer. 1870. 384 p.

[“ “Premiums Awarded in 1868”

Transactions of the Seventh Department.

Paintings, Drawings, Etc.

———————————————————————————————————————————

Exhibitor. Residence. Article. Premium.

———————————————————————————————————————————

W. L. Marple San Francisco. Oil painting $20

Norton Bush. San Francisco. Oil painting $20

W. L. Marple San Francisco. Landscape oil painting. $10

Norton Bush. San Francisco. Landscape oil painting. $10

Colonel Warren San Francisco. Collection of lithographs and engravings Diploma.

Mrs. W. E. Brown… Sacramento…. Flower painting. First-$10

Otto Schrader. San Francisco. Fruit painting First-$10

Mrs. G. D. Stewart. Sacramento…. Crayon drawing. Diploma.

J. B. Grouppe….. San Francisco. Wood engraving. Diploma.

Joseph F. Hess San Francisco. Pencil drawing. Diploma.

Mrs. G. D. Stewart. Sacramento…. Water color painting… First-$20

F. Serregni…….. San Francisco. Penmanship and pen drawing. First-Diploma and $5

J. W. Cherry San Francisco. . Sign painting. First – Diploma.

Wm. Shew. San Francisco. Plain photographs, life size. First-$15

Wm. Shew… San Francisco. Photograph in water color.. First-$15

Wm. Shew… San Francisco. Photograph in India ink……. First-$10

Wm. Shew….. San Francisco. Plain sun pearl. First-$15.

Wm. Shew San Francisco. Porcelain picture, colored…. First-$10

Silas Selleck.. San Francisco. Plain photograph, medium size. First-$10

C. E. Watkins…. San Francisco. Landscape photograph (collection). Special-$10

Thos. Houseworth… San Francisco. Collection of landscape photographs Special-$10

———————————————————————————————————————————

Sculpture. (Etc, etc.)

———————————————————————————————————————————

Musical Instruments. (Etc., etc.)

———————————————————————————————————————————

(p. 110)

“Noteworthy Exhibitions.” (p. 111)-

[“Under this heading we make brief mention of such displays in the Pavilion as from their nature or workmanship merit a careful scrutiny; but we do not wish to have the inference drawn that a failure to specially notice implies lack of merit in any particular exhibition. The Mission Woollen Mills, of San Francisco, Lazard Freres, agent, had a fine display of blankets, from the rough but useful miners’ blanket, to the soft and silky covering that adorns the luxurious couch, and a large variety of tweeds, cassimeres and beavers; besides ladies’ cloakings and flannels of the finest texture, and buggy robes and sluice blanketings. These mills were represented in the Exposition Universalle at Paris, where they were awarded a gold medal. We are told that they now employ three hundred men, and have fifty looms, six thousand spindles, and eleven sets of cards in operation. The goods they manufacture are a credit to our State. Dr. A. Folleau, of San Francisco, anatomical machinist, exhibited a case of artificial limbs and apparatus for human deformities, which attracted considerable attention from surgeons and physicians. Among the apparatus exhibited by him, are some for lateral curvature of the spine, for hip joint diseases, for club feet, for contraction of the muscles of the neck, and for deformities of the neck (torticoli). He had also a collection of trusses for inguinal, femoral, scrotal and umbilical diseases. The whole of the exhibition was manufactured in the City of San Francisco by the exhibitor, and many of the most meritorious particulars are the production of his inventive faculties. His artificial legs can be manufactured at the same price as those made in Philadelphia, and combine lightness with all necessary solidity. Liddle & Kaeding, of San Francisco, exhibited a collection of revolvers, guns, rifles, pistols, etc., and what they claim to be the first breechloading gun ever made on the Pacific Coast. They also exhibited a double-barrelled shot-gun, with a California laurel stock, and mounted with Washoe silver-the first time laurel was ever used for the purpose. They also had a large variety of sporting goods and fishing tackle….” (Etc., etc.) (p. 111)

“…W. L. Marple, of San Francisco, exhibited the finest pictures in the art gallery-comprising views of the Golden Gate, of Cascade Lake, the Summit from near Hawley’s, Lake Valley, and two views on Napa (p. 113) Creek. As at the Mechanics’ Institute Fair, these paintings were constantly surrounded by admiring groups of visitors, and elicited high eulogiums from those who claim to be art connoisseurs. No lover of art failed to examine carefully these very meritorious productions.

Thomas Houseworth & Co., of San Francisco, displayed photographic views of numerous localities and natural curiosities of the Pacific coast. Their collection was varied and interesting.

William Shew, of San Francisco, occupied a large space in the picture gallery with ivory types, sun pearls, cabinet and card photographs, and other choice productions of the daguerrian art, including portraits of many distinguished persons.

Silas Selleck, of San Francisco, also exhibited cabinet portraits, and plain and retouched photographs.

Norton Bush, of San Francisco, exhibited his fine series of paintings of the gorgeous tropical scenery of the Isthmus of Darien, including a view of Panama. Aside from their high artistic merits, they are interesting from the associations they recall in the minds of a large proportion of the visitors. He also exhibited “Mount Diablo,” from nature.

Mrs. C. Cook, of San Francisco, showed a case of beautiful hair jewelry, comprising bracelets, earrings, finger-rings, breastpins, etc. This collection was especially admired by lady visitors

P. Mezzara, of San Francisco, contributed some of his exquisitely cut cameos and some very fine busts. This gentleman has his studio at Bradley & Rulofson’s photographic gallery, San Francisco. As our State advances in the fine arts the productions of his genius are growing more and more in public estimation.

Mrs. G. D. Stewart, of Sacramento, exhibited three fine crayon sketches, entitled “The Bridge of Toledo,” “Apollo,” and “The Windmill.” She also exhibited three pictures of Scottish scenery in water colors. These pictures are from nature, were executed in earlier years, and embarrassed circumstances induces the lady artist to offer them for sale.

C. E. Watkins, of San Francisco, landscape photographer, exhibited in the gallery a large number of very fine views of scenes upon the Columbia River, and of many of the most beautiful landscapes and interesting natural curiosities of California and Oregon, including very large sized photographs of Portland and Oregon City. These views are executed in the highest style of the photographic art.

Serwais Tonnar, of San José, exhibited a rustic settee of heart maple, buckeye and redwood; and a rustic chair of the same woods, ornamented with shells. He also showed specimens of grafting wax-his own invention-which he claims to be superior to any other in use; and a pruning saw, also his own invention, which he claims does its work better and quicker than any other saw. Practical men speak highly of these two latter articles….” (p. 114) (Etc., etc.)]

Whitney, J. D. Report of the Commissioners to Manage the Yosemite Valley and the Mariposa Big Tree Grove, for the Years 1866-7. San Francisco: Towne and Bacon. 1868. 14 p.

[“…As early in 1865 as the season would permit, a party was organized by the State Geologist for the purpose of making a detailed geographical and geological survey of the region of the high Sierra adjacent to the Yosemite Valley. This party consisted of C. King, J. T. Gardner, H. N. Bolander, and C. R. Brinley, with two men employed to pack and cook. They commenced work early in June, and continued in the field until the latter end of October, being accompanied by the State Geologist during a portion of the time. Owing to unavoidable causes, this party was obliged to return from the field before the work was completed. But enough had been done to enable Mr. Gardner to commence and partly finish a map, and the following plan of publication was determined on by the State Geologist. The work will consist of text, maps, and photographic and other illustrations, and two editions will be issued-one without photographs, the other with them. One will be called the “Yosemite Guide Book,” the other the “Yosemite Gift Book.” The Guide Book will contain the text of the Gift Book and the same maps, but the photographic illustrations will be omitted. The text will be such as will be suitable for a complete and thorough guide, or hand-book, to the Valley and its surroundings, including the high Sierra, and, in general, the region between Mariposa and Big Oak Flat on the west, and the head of the San Joaquin and Mono Lake on the east. The map of the region thus designated is drawn on a scale of two miles to one inch, and is thirty inches by twenty in size. It contains all the minute details of the topography of one of the most elevated and roughest portions of the State, and is the first accurate map of any high mountain region ever prepared in the United States. The surveys for the completion of this map were continued during the months of August and September of the present year, by a party of the Geological Survey, in charge of C. F. Hoffmann, and the work is now complete, and the map ready for the engravers. The photographic illustrations, twenty-four in number, made by C. E. Watkins, (p. 5) with the Dallmeyer lens of the Survey, are also all printed and delivered, and the work can be put to press as soon as the State Geologist has time to attend to it. It is believed that it will be one of the most elegant books ever issued from an American press, and that it will have no little influence in drawing attention to the stupendous scenery of the Yosemite and its vicinity.

Mr. Hoffmann and party also made a careful survey of the bottom of the valley, including all the land within the talus or débris fallen from the walls, and this work has been plotted on a scale of ten chains to one inch, making a map fifty inches by thirty in size, with the number of acres in each tract of meadow, timber and fern land designated upon it, and also the boundaries of the claims of the settlers in the valley, and the number of acres inclosed and claimed by them. This map was found to be necessary for the purposes of the Commission, and an appropriation will be asked for to pay the expense of the survey and of preparing the map.

The principal grove of trees in the Big Tree Grant has also been carefully surveyed by the State Geologist, assisted by Hoffmann, each tree of over one foot in diameter measured, and the height of a number of them accurately determined. There are in the main grove, of trees over one foot in diameter (that is, of the Big Trees or Sequoia gigantea), just three hundred and sixty-five, besides a great number of smaller ones. The trees thus measured have been plotted and numbered, so that their exact position and size relative to each other can be seen at a glance.

The Commissioners, seconded by the Geological Survey, have thus done all that is for the present requisite toward obtaining all the necessary statistical data in regard to the valley and grove, and for making this information public in an attractive form. It may be added that the Yosemite Guide-book and the Yosemite Gift-book will both be sold, as are other publications of the survey, and the proceeds paid into the treasury of State, for the benefit of the Common School Fund….” (p. 6) (Etc., etc.)]

Transactions of the California State Agricultural Society during the Years 1868 and 1869. Sacramento: D. W. Gelwicks, State Printer, 1870. 384 p. illus.

Premiums Awarded in 1868.

Seventh Department.

Paintings, Drawings, Etc.

Exhibitor. Residence. Article. Premium.

W. L. Marple San Francisco. Oil painting $20

Norton Bush San Francisco. Oil painting $20

W. L. Marple.. San Francisco. Landscape oil painting. $10

Norton Bush San Francisco. Landscape oil painting $10

Colonel Warren San Francisco Collection of lithographs and engravings Diploma.

Mrs. W. E. Brown Sacramento Flower painting First $10

Otto Schrader San Francisco Fruit painting First $10

Mrs. G. D. Stewart Sacramento Crayon drawing. Diploma.

J. B. Grouppe San Francisco. Wood engraving. Diploma.

Joseph F. Hess San Francisco. Pencil drawing Diploma.

Mrs. G. D. Stewart. Sacramento Water color painting First $20

F. Serregni San Francisco Penmanship and pen drawing First – Diploma and $5

J. W. Cherry San Francisco Sign painting First—Diploma.

Wm. Shew San Francisco Plain photographs, life size First—$15

Wm. Shew San Francisco Photograph in water color. First—$15

Wm. Shew San Francisco. Photograph in India ink. First—$10

Wm. Shew San Francisco. Plain sun pearl First—$15

Wm. Shew San Francisco. Porcelain picture, colored First—$10

Silas Selleck San Francisco. Plain photograph, medium size First—$10

C. E. Watkins San Francisco. Landscape photograph

(collection)Special—$10

Thos. Houseworth San Francisco. Collection of landscape photographsSpecial—$10

Sculpture.

Exhibitor. Residence. Article. Premium.

P. J. Devine San Francisco. Sculpture—A child’s bust First $10

J. C. Devine Sacramento Collection of marble work First—$30

Jos. Dunkerley San Francisco. Collection of prepared birds. First and diploma—$15

P. Mezzura San Francisco Collection of medallions Special—$10..

(p. 110)

Noteworthy Exhibitions.

Under this heading we make brief mention of such displays in the Pavilion as from their nature or workmanship merit a careful scrutiny; but we do not wish to have the inference drawn that a failure to specially notice implies lack of merit in any particular exhibition.

The Mission Woollen Mills, of San Francisco, Lazard Freres, agent, had a. fine display of blankets. from the rough but useful miners’ blanket, to the soft and silky covering that adorns the luxurious couch. and a large variety of tweeds, cassimeres and beavers; besides Iadies’ cloakings and flannels of the finest texture. and buggy robes and sluice blanketings. These mills were represented in the Exposition Universalle at Paris, where they were awarded a gold medal. We are told that they now employ three hundred men, and have fifty looms, six thousand spindles, and eleven sets of cards in operation. The goods they manufacture are a credit to our State.

Dr. A. Follcau, of San Francisco. anatomical machinist, exhibited a case of artificial limbs and apparatus for human deformities, which attracted considerable attention from surgeons and physicians. Among the apparatus exhibited by him, are some for lateral curvature of the spine, for hip joint diseases, for club feet, for contraction of the muscles of the neck, and for deformities of the neck (torticoli). He had also a collection of trusses for inguinal, femoral, scrotal and umbilical diseases. The whole of the exhibition was manufactured in the City of San Francisco by the exhibitor, and many of the most meritorious particulars are the production of his inventive faculties. His artificial legs can be manufactured at the same price as those made in Philadelphia, and combine lightness with all necessary solidity.

Liddle & Kaeding, of San Francisco, exhibited a collection of revolvers, guns, rifles, pistols, etc., and what they claim to be the first breechloading gun ever made on the Pacific Coast. They also exhibited a double-barrelled shot-gun, with a California laurel stock. and mounted with Washoe silver—the first time laurel was ever used for the purpose….” (p. 111)

W. L. Marple, of San Francisco, exhibited the finest pictures in the art gallery—comprising views of the Golden Gate, of Cascade Lake, the Summit from near Hawley’s, Lake Valley, and two views on Napa (p. 113) Creek. As at the Mechanics’ Institute Fair, these paintings were constantly surrounded by admiring groups of visitors. and elicited high eulogiums from those who claim to be art connoisseurs. No lover of art failed to examine carefully these very meritorious productions.

Thomas Houseworth & Co, of San Francisco, displayed photographic views of numerous localities and natural curiosities of the Pacific coast. Their collection was varied and interesting.

William Shew, of San Francisco, occupied a large space in the picture gallery with ivorytypes, sun pearls, cabinet and card photographs, and other choice productions of the daguerrian art, including portraits of many distinguished persons.

Silas Selleck, of San Francisco, also exhibited cabinet portraits, and plain and retouched photographs.

Norton Bush, of San Francisco, exhibited his fine series of paintings of the gorgeous tropical scenery of the Isthmus of Darien, including a view of Panama. Aside from their high artistic merits, they are interesting from the associations they recall in the minds of a large proportion of the visitors. He also exhibited “Mount Diablo,” from nature.

Mrs. C. Cook, of San Francisco, showed a case of beautiful hair-jewelry, comprising bracelets, ear-rings, finger-rings, breastpins, etc. This collection was especially admired by lady visitors

P. Mezzara, of San Francisco, contributed some of his exquisitely cut cameos and some very fine busts. This gentleman has his studio at Bradley & Rulofson’s photographic gallery, San Francisco. .As our State advances in the fine arts the productions of his genius are growing more and more in public estimation.

Mrs. G. D. Stewart, of Sacramento, exhibited three fine crayon sketches, entitled “The Bridge of Toledo,” “Apollo,” and “ The Windmill.” She also exhibited three pictures of Scottish scenery in water colors. These pictures are from nature, were executed in earlier years, and embarrassed circumstances induces the lady artist to offer them for

sale.

C. E. Watkins, of San Francisco, landscape photographer, exhibited in the gallery a large number of very fine views of scenes upon the Columbia River, and of many of the most beautiful landscapes and interesting natural curiosities of California and Oregon, including very large sized photographs of Portland and Oregon City. These views are executed in the highest style of the photographic art.

Serwais Tonnar, of San José, exhibited a rustic settee of heart maple, buckeye and redwood; and a rustic chair of the same woods, ornamented with shells. He also showed specimens of grafting wax—his own invention—which he claims to be superior to any other in use; and a pruning ‘saw, also his own invention, which he claims does its work better and quicker than any other saw. Practical men speak highly of these two latter articles….” (p. 114)

Miss Lillie Hamilton, aged thirteen years, exhibited a fine pieced quilt, evincing much care and taste.

Mrs. A. D. Whitney showed a very prettily arranged medley picture.

Miss Sarah C. Marvin, of Sacramento, exhibited a hair bouquet, very tastily arranged.

Mrs. William .H. Hobby, of Sacramento, also exhibited a very pretty hair bouquet.

Mrs. R. J. Merkley, of Sacramento, exhibited a beautiful wreath of feather flowers.

Mrs. S. M. Coggins, of Sacramento, exhibited specimens of retouched photographs, evincing skill and good judgment.

Miss Mollie Tittle exhibited some very fine crochet work tidies and a pretty bead cushion.,

Miss Maggie Ormsby, of Sacramento, exhibited some very pretty embroidery Work.

Miss Annie E. Hoag, of Washington, exhibited some neat worsted picture frames and embroidery on perforated card-board.

Miss Lottie Hoffman, of Sacramento, exhibited some very fine silk embroidery and water-color paintings….” (p. 119)

—————————————

Premiums Awarded in 1869.

Seventh Department.

Fine Arts.

Exhibitor. Residence. Article. Premium.

Norton Bush San Francisco. Best painting in oil $20

Norton Bush San Francisco Best painting in oil (tropical scene) $20

Mrs. G. D. Stewart Sacramento Best water colored painting Diploma.

A. A. Hart Sacramento Best uncolored photograph $10

G. W. Baker Sacramento Best lithography Diploma.

J. B. Grouppe San Francisco Best wood and seal engraving Diploma

Pacific Business College San Francisco Best penmanship $5

Mrs. W. E. Brown Sacramento Best crayon drawing Diploma.

Mrs. G. D. Stewart Sacramento Best pencil drawing Diploma

P. J. Devine San Francisco Best sculpture (bust) $10

Wm. Shew San Francisco Best plain photograph, life size $15

Wm. Shew San Francisco Best plain photograph, medium $10

Mrs. S. M. Coggins Sacramento Best photograph, in water color $15

Wm. Shew San Francisco Best plain porcelain picture $15

Mrs. S. M. Coggins Sacramento Best colored porcelain picture $10

Mr. Serregni San Francisco Best pen drawing Diploma.

Norton Bush San Francisco Best display of oil paintings $20

J. Wise San Francisco Portrait in oil Special— $10

D. H. Woods Sacramento Oil painting (landscape) Special—$10

W. E. Brown Sacramento Oil painting (St. Jerome) Special—$10

John Cooper Sacramento Best flute $5

(p. 206)

Noteworthy Exhibitions.

“…Norton Bush, the gifted young California artist, contributed quite a number of his beautiful pictures, including “Chagres River,” “Glimpse of Tropic Land,” two “Tropical Sketches,” “Lake Tahoe,” “Donner Lake,” “American River, near the Summit,” “Bay of Panama,” “Castle Rock,” and “Sketch in the Straits of Carquinez.” His tropical pictures were especially meritorious, and received high encomiums from the critical. The gorgeousness and indolence of tropic life are favorite subjects with Bush, and in their delineation he excels. The two small oval framed pictures, entitled “Tropical Sketches,” were gems in their way.

J. Wise, of San Francisco, exhibited several fine oil portraits of gentlemen and ladies, as samples of his skill in that art.

William Shew, of San Francisco, contributed a. large collection of photographs including ivorytypes, pearl pictures, etc., most of which, through their constant presence at our State fairs, have become quite familiar to our citizens. The pictures are very life-like, and bear very favorable testimony to the quality of the work produced at this gentleman’s gallery.

Mrs. Sarah M. Coggins, of Sacramento, exhibited some beautiful specimens of her skill with the brush in coloring photographs. The samples on exhibition were very delicately and truthfully tinted, and worthy of close attention.

Mrs. W. E. Brown, of Sacramento, had on exhibition several very fine oil paintings, including “Donner Lake, Sunrise,” “Donner Lake, Sunset,” (p. 211) “Medora,” “St. Jerome,” and “Winter.” They all evince care and talent, and received much praise.

Howard Campion, of Sacramento, showed “A Sporting Scene,” “Portrait of General Grant,” and “Emerald Bay, Lake Tahoe.” A great deal can be truthfully said in favor of all his pictures; but the portrait of General Grant, whatever may be its merits in an artistic point of view, does not convey a correct idea of the features and figure of the present President. The expression of the countenance is not faithful to life, and Grant is not so large a man as the picture would lead us to imagine. “Emerald Bay” we prefer to all the rest; it is a pretty, evenly-toned picture, and possesses the attribute of merit of being pleasing to look upon. .

Mrs. G. D. Stewart, of Sacramento, contributed some water-color paintings, including “Sacramento City Cemetery,” “A Seaside Sketch,” and “Balmoral Castle.” Also, two crayons, “Pagan Rome” and “Christian Rome.” The two latter, especially, are very creditable, but they all deserved close inspection.

A full-length needlework picture of General Washington, made by the pupils of St. Joseph’s Convent, in this city, was very much admired, by the ladies particularly, though its excellence is sufficiently apparent to be appreciated by all. Quite a knot of spectators was almost always congregated in front of it during exhibition hours.

T. Rodgers Johnson, of San Francisco, exhibited a case of his finely worked regalias and emblems of the Odd Fellow, Masonic, Good Templar and other orders.

Drs. Folleau & Mabon, of San Francisco, had a show-case containing orthopedic apparatus for the hip disease, improved surgical appliances for ladies, orthopedic apparatus for club feet, orthopedic apparatus for angulaire curvature (Potts’ disease), artificial limbs and patent improved trusses. The collection was of special interest to medical and surgical gentlemen, and to those who are unfortunately afflicted with the various ailments which these contrivances are designed to alleviate or cure….” (p, 212)]

The Valley of the Grisly Bear. London: Sampson Low & Marston, 1870. n. p. 100 plus b & w. [Album containing original photographs by Albert Bierstadt and Carleton E. Watkins. (Its unclear from the library citation whether this a published album or a compilation.]

1871

The Alta California Pacific Coast and Trans.Continental Rail-Road Guide

Contains more information about the States and Territories of the Pacific

Coast, and those traversed by the Great Trans-Continental Railroad,

than any other Book extant. It gives a minutely detailed account

of every City, Town, Railroad Station, Mining District, Moun-

tain, Valley, Lake, River, Hunting and Fishing Ground

along the Great Trans-Continental Railroad, together

with an account of CALIFORNIA, ITS INDUS-

TRIES, LAND, CLIMATE, AND HOW NEW-

COMERS CAN OBTAIN PUBLIC LAND.

It is Profusely Illustrated with Excellent Views of the grand scenery of

the Sierra Nevada and Rocky Mountains, and contains full informa-

tion about all the Towns and Cities adjacent to the Cal. P. R. B.,

the C. P. R. R., the S. P. R. R., the U.P. R. R., and the

Utah Central R. R., together with their connections

by Rail, Stage, and Steamer. It will tell you

where to find the Mines, what they

yield, where to go, how to go,

where to Fish, and where

TO HUNT THE BUFFALO, THE ANTELOPE, AND THE ELK.

J. C. FERGUSSON, Editor and Manager.

San Francisco Cal: Fred MacCrelish & Co., 1871., 293 p., plates: illus., map. 18 cm.

—————————————

[ “Index.”

“Illustrations.

A Valley in the Sierra Nevada Mountains, (Frontispiece)

“From a sketch by Fred. Whymper.” “Engraved by G. W. ShourdS.”

Bay of San Francisco 73

“From a sketch by Fred. Whymper,” “Engraved by G. W. Shourds.”

Bear River Bay, Great Salt Lake, U. T. 212

“Drawn by Nahl Bros., San Francisco.” “Engraved by G. W. Shourds, San Francisco.”

Pleasant Valley, Nevada 193

“From a Photograph by Watkins.” “Engraved by G. W Shourds.”

The Grand Hotel, San Francisco, California 55

“Shourds SC”

The Mormon Tabernacle, Salt Lake City, U. T. 218

“From a Photograph by Savage & Ottinger.” “Engraved by G. W. Shourds.”

The Snow Sheds on the C. P. R. R., Sierra Nevada Mountains, Cal. 145