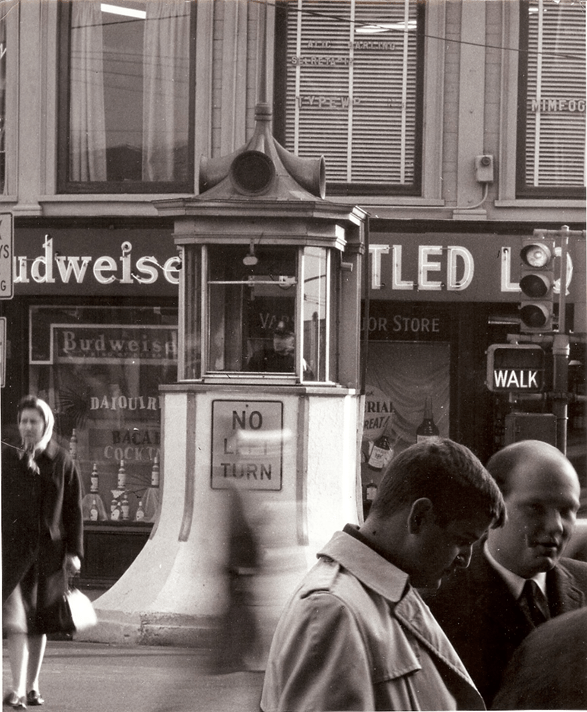

“Self Portrait with Camera,” copyright Elsa Dorfman. (Photographic post-card)

The first time I met Elsa Dorfman was in 1975, just before Christmas, in Harvard Square. Harvard Square is a slight misnomer. It is really more like a triangle where Mass. Ave. (a major thoroughfare) comes out of Boston across the river, then runs through Cambridge from east to west for a mile or so, then turns a corner at the oldest western part of the Harvard Yard and runs north to Porter Square in northern Cambridge, then turns northwest for several more miles through Somerville, Arlington and then on out of my awareness. Several smaller streets converge at that triangle point, which held a newspaper and magazine stand positioned on the closed subway entrance. Brattle St., and a street now called John F. Kennedy St. (It had a different name when I was there, I think it was called Mount Auburn Street.) met at the triangle point. The “Square” was actually a clutter of commercial businesses that clustered for a few blocks around the Mass. Ave turn. Several bus routes ended there. A bank with mysterious second floor offices held one corner. The Harvard Coop, where you bought books and Harvard memorabilia (scarfs and sweatshirts and chairs, if you wanted that kind of thing) dominated another corner, with plenty of other bookstores where you bought both new and used books back down Mass. Ave for several blocks, shops where you bought dishes and towels and stuff, hole-in-the-wall cafes where you bought some of the best sandwiches in the world, a larger, more formal German-American restaurant where you could get a full sit-down meal, other restaurants, an administration building for Harvard University (Bursar’s Office, Clinic, Harvard Press Office, etc.), even a movie theatre; all were clustered below Mass Ave. on the south to southwest; while the quieter, walled-off Harvard Yard held the north-north-east corner.

In those days Harvard Square was an active, bustling place.

Harvard Square, ca. 1975. Photos by William Johnson.

Students and teachers and tourists and commerce of all sorts during the day, and on the summer weekend nights – buskers, jugglers, with music from steel-drum bands or the hippy, guitar-playing, folk singers. And at Christmas time street vendors were allowed to sell hand-made crafts and food and other good things from temporary booths on the sidewalks in and around the Square.

One Christmas season I found a short, boxy, plainly dressed woman selling her photographs from a grocery-shopping cart on the sidewalk in front of the Harvard administration building. But this was not your typical craft-fair vendor, with the decorative photographs you would typically find in this sort of situation. As I looked more closely, I realized that these were serious black & white photographs, about 8” x 10”, carefully seen and photographed, carefully printed, and carefully mounted on board; and she was selling them for $2.00 or $5.00 each. She had to be taking a loss on the cost of the materials alone.

I loved it. In the academic circles I was embedded in at the time, where there was still a struggle to get photography recognized as legitimate by the “high-art” people, things could occasionally get pretentious around the notion of “Fine Art Photography” and I just loved it that this woman seriously liked to make

good photographs and she seriously wanted to make them easily available to anyone who liked them.

So I bought one.

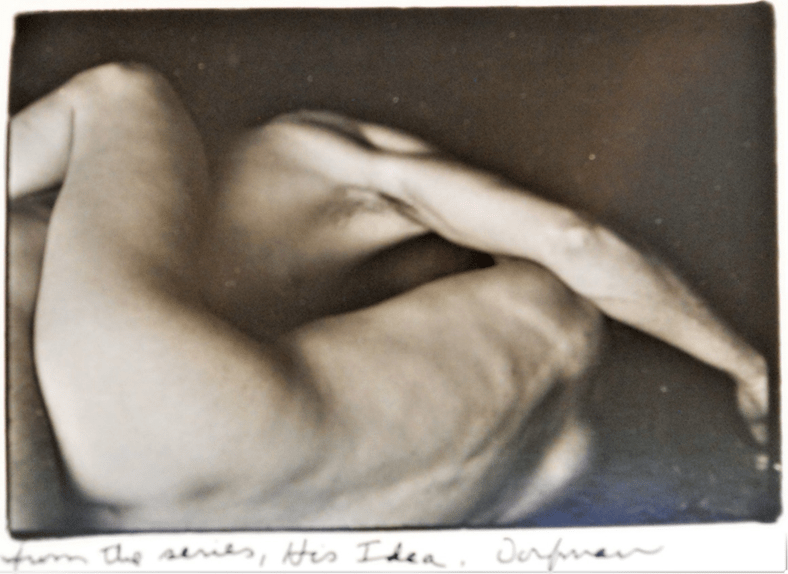

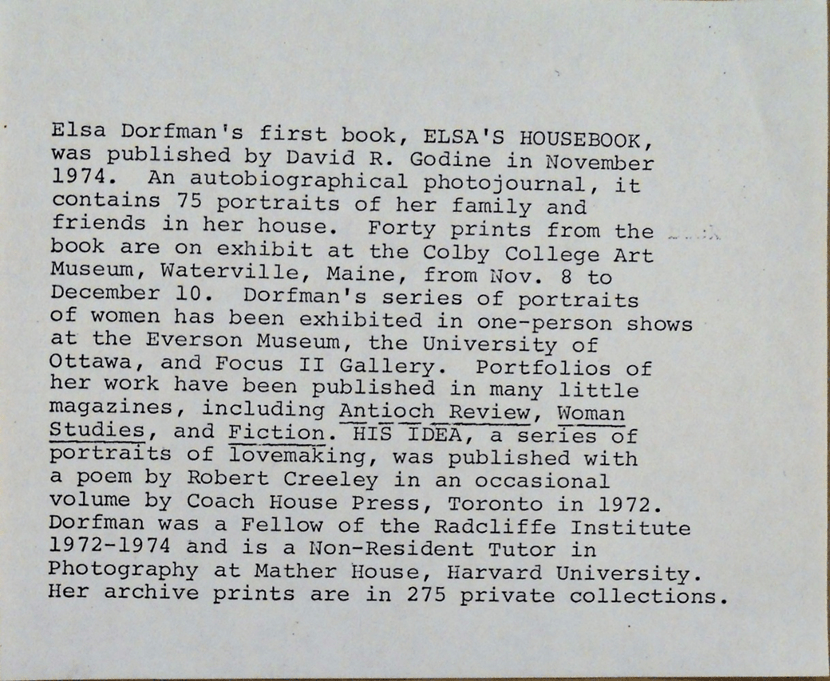

It came in a plastic bag with its own information card.

At that time, separated from my first wife, I was living very cheaply in a tattered one-room basement apartment just outside of Harvard Square. Elsa lived a few blocks away and occasionally we would run into each other on the street and chat. Once she invited me to lunch at her house to meet her husband, who I remember as a very quiet and somehow sweet little man who apparently was a very serious lawyer out in the real world. I learned that not only was Elsa a very good cook but that Robert Creely, the poet who had let her use his poem for her book, was a good friend and that Elsa was also friends with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, Peter Orlovsky, and other artists of the “Beat” movement in New York in the ‘50s.

And, more interesting to me at the time, that she had worked for the avaunt-guard publisher Grove Press and had literally couriered Robert Frank’s photographs for the US version of The Americans back and forth between the publisher and the artist while it was being developed. In the early 1970s Robert Frank had not yet attained the exalted status he has today. He was still an apparently reclusive, slightly mysterious, figure who’s book had been roundly trashed by every established photographic critic when it first came out but which was stirring up increasing levels of interest and appreciation within the younger generation of photographers and critics. I was one that younger generation and I was beginning to fall under the spell of that book’s power.

Then in 1976 I moved to Rochester, New York to teach at Nathan Lyon’s Visual Studies Workshop and then on to the Center for Creative Photography at Tucson Arizona to work with W. Eugene Smith and, after his death, to organize his photographic collection. I also married again, to Susie Cohen. I had met Susie in Boston, but we dated in Rochester and married in Tucson. All this took several years and after various projects and events we wound up in Boston again in the mid ‘80s where we had come back to work on an experimental project and exhibition that I had somehow talked Eelco Wolf, a Vice-President at Polaroid to support. That project had run its course and Susie and I were engaged in several concurrent or overlapping projects to earn our daily bread. One of those projects was to take over the editorship of Views: The Journal of Photography in New England, published by the new Photographic Resource Center, then at Boston University. The journal was in editorial disarray at the time, and it took Susie and me a little while to build it back up to the point where it became what was described as “…one of the most important academic‑style journals in photography.” (The Photographer’s Source) which “…set the standard by which other photo center quarterlies should be judged.” (Afterimage).

One of the people who helped rebuild the journal was Elsa. She showed up one day and offered to write a “gossip column.” Which she did and did well – digging up and collating items of news and interest about the photographic community at large by calling people on the phone and chatting and finding out about their professional activities (Exhibitions, awards, etc.) and their personal lives (Marriages, births, etc.); which she presented with the same effortless grace and humor that she brought to her picture making. Some thought that sort of information was outside the scope of the journal. Susie and I thought it helped balance the academic rigor with some human feeling.

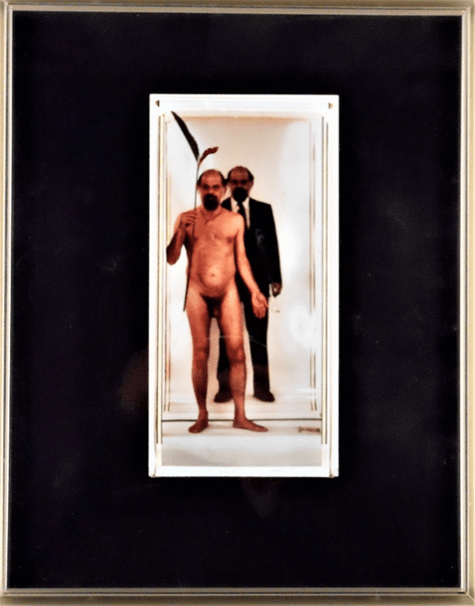

Elsa was also by this time making the 20 x 24 inch Polaroid portraits for which she was to become famous.

“Dorfman had the only privately owned, 240-pound accordion-like box instant Polaroid Land camera.

Polaroid made only about a half dozen of them. Dorfman couldn’t say why she would only work with this

rare enormous camera with its fragile film and chemical pods that were hard to come by, especially after

Polaroid went bankrupt twice in the 2000s and stopped selling instant film in 2009. She just knew that

when she found the camera in 1980, she was smitten.

There were five cameras built and then they were kind of underused, so [Elsa] really lobbied to get

one her own,” Reuter said. “The irony is she leased the camera and she leased it for so long she could

have bought three of them.”

ttps://www.wbur.org/news/2020/05/31/cambridge-photographer-elsa-dorfman-giant-polaroids-dies.

By the late 1980’s the Polaroid Corporation was in the process of closing down and it had divested itself from the various artist’s programs that it had supported a few years before. (Among them the “Creativity Project” that Susie and I had developed with the artists Robert Frank, Dave Heath, Robert Heinecken and John Wood, which, among other things, had used the 20 x 24 Polaroid camera at the studio located in the Art School at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. I think that most of the other cameras scattered around the world were no longer in use, or definitely no longer in continious use. But Elsa had somehow managed to talk some Polaroid executive or other into renting her the Boston 20 x 24 camera, which she then used commercially to make studio portraits – mostly of family groups. I don’t know for certain, but she may have been the only person in the world at that time regularly using a 20 x 24 inch camera and almost certainly the only one regularly usng the 20 x 24 format for commercial portraits.

We asked Elsa to make a 20 x 24 photo of Susie and our son Joshua in 1986. Elsa asked Susie to bring Joshua with some of his toys to the BMFA studio where the camera was still located – which, by accident, we were already familiar with. Elsie asked Susie and Josh to sit on the floor, quickly arranged the photograph and took the picture. The huge wooden camera with its bellows extension, its narrow range of possible operations, and its awkward but immediate processing of the image (You can search “Polaroid Project” or “Robert Frank” on this blog for more information about that 20 x 24 camera and its processes and proceedures.) gave to the session the flavor of a 19th century daguerrian portrait gallery. But Elsa’s charm and her fluid control over the system made the event an easy and pleasant experience.

“Susie and Josh on the 20 x 24 on May 8, 1886.” 20” x 24” Polaroid print. Copyright Elsa Dorfman.

Then, when we left Boston in 1987 to return to Rochester for me to work at the George Eastman House, Elsa surprised us with a wonderful gift. By the 1980s Allen Ginsberg, once reviled, had become a celebrated iconic figure in American culture and his long, semi-secret involvement with photography had just begun to become publicly known. Susie and I met with him, possibly with the help of Elsie’s recommendation, to plan an article for Views, but then we moved to Rochester before we could complete that project.

As a parting gift Elsa gave us a 20 x 24 Polaroid portrait of Allen Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky, signed by both poets. It was an exceptionally generous act, as well befitted her character and nature.

“Alan Ginsberg and Peter Orlovsky. March 28, 1985.” 20” by 24” Polaroid print. Copyright by Elsa Dorfman.

Elsa continued to send us postcards and little gifts over the years; although as I am a terrible correspondent, I was always tardy with any responses. But I always appreciated hearing from her.

“Allen, November 6, 1986.” reduced copy of 40” x 80 Polaroid print, 1991. Copyright Elsa Dorfman.

I was saddened to learn that Elsa had died in 2020 – which I didn’t even know about until I started writing this note. Her intelligence and spirit will be missed. I also apologize for the quality of the reproductions presented here, the original photos are much better.

“Allen, November 6, 1986.” reduced copy of 40” x 80 Polaroid print, 1991. Copyright Elsa Dorfman.

I was saddened to learn that Elsa had died in 2020 – which I didn’t even know about until I started writing this note. Her intelligence and spirit will be missed. I also apologize for the quality of the reproductions presented here, the original photos are much better.